From the Chicago Reader (April 5, 1996). — J.R.

The Neon Bible

Directed and written by Terence Davies

With Gena Rowlands, Diana Scarwid, Jacob Tierney, Denis Leary, Leo Burmester, Frances Conroy, and Peter McRobbie.

Two paradoxical facts about Terence Davies’s first film adaptation:

(1) It follows fairly closely The Neon Bible, a novel written by John Kennedy Toole for a literary contest in the mid-50s, when he was 16 — a decade before he finished work on his second novel, A Confederacy of Dunces, and about 15 years before he, still unpublished, committed suicide (A Confederacy of Dunces was published ten years later, The Neon Bible ten years after that). I don’t care much for The Neon Bible, a hackneyed mood piece set in a rural backwater of the deep south, but I think the movie, which seems 100 percent Davies, is wonderful.

(2) Of all the English-speaking films shown at Cannes last May, the two that got the most boorish and least comprehending reception by the English-speaking press were The Neon Bible and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, though for nearly opposite reasons. Jarmusch, who’s long been criticized for coasting along in Down by Law, Mystery Train, and Night on Earth on the same kind of hip humor he virtually invented for Stranger Than Paradise, finally broke free and did something bold, original, political, dark, scary, outspoken, witty, and often beautiful — a black-and-white western that should be opening here sometime next month. But because he dared to criticize this country, a sizable portion of the American press — which didn’t even seem to be consciously aware of this criticism — either scratched its head or sneered to cover its bafflement. (By contrast, Dead Man has been well received in Japan and much of Europe, where a relatively straightforward presentation of this country’s violence, ignorance, and overall dementia doesn’t create the same problems.)

Davies, an Englishman born in 1945, shot for the first time in ‘Scope, in a country and culture different from his own, and his film is a faithful adaptation of someone else’s material, set in a period that precedes Davies’s autobiographical Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes and starring Gena Rowlands, an actress whose methods have little in common with those of anyone he’s ever worked with before. And what did the American press complain about? That The Neon Bible was a carbon copy of Davies’s two previous films.

I suppose it could be argued that Davies’s capacity to make something at once completely different from and exactly the same as his earlier work is a rather uncommon achievement — shared perhaps with Yasujiro Ozu and Howard Hawks at various points in their careers, but not with many others. The Neon Bible may not qualify as a masterpiece, as Distant Voices, Still Lives and The Long Day Closes do, but it still contains moments and achievements that are as impressive as anything Davies has ever done — and to have done this with alien material makes his achievement even more remarkable.

One of the principal things Davies and Toole seem to have in common as artists is something negative — a lack of distinction as storytellers. In their relatively mature works (Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces, Davies’s films from Distant Voices, Still Lives on) they’re both masters of set pieces who have trouble getting from one to the next; the kind of graceful narrative flow that might connect such passages into a seamless larger form is foreign to them. Yet stasis rather than narrative development is basic to what both artists can do best. In Toole’s case, it’s a talent for defining character and life itself as a kind of quagmire from which nothing and no one escapes — a talent that focused mainly on morose, passive suffering and deprivation in The Neon Bible and turned to satire (most of it liberal bashing) in A Confederacy of Dunces. (Given the enormous differences between the two novels, it’s worth entertaining the hypothesis that The Neon Bible was written by Toole’s flamboyant mother, now also dead; it certainly doesn’t read like the work of either a 16-year-old boy or the New Orleans disciple of Alexander Pope who would write A Confederacy of Dunces.)

This gravitation toward stasis is related to a capacity to reproduce or evoke states of pure feeling connected to intense childhood memories. If you’ve seen Distant Voices, Still Lives or The Long Day Closes you know what to expect in The Neon Bible: stretched-out meditative moments in which nothing in particular happens except on the sound track (a radio speech by FDR, an episode from Gang Busters); community rituals, such as church meetings, tent revivals, and such everyday events as people walking down the street to church or the train station; and short, awkward bursts of dialogue or dramatic action that usually serve as mortar for these extended blocks of material.

Roughly speaking, the time span covered in The Neon Bible (the movie) is the late 30s through the mid-40s. Toole was born in 1937, Davies in 1945, and David, the lead character (played at the age of ten by Drake Bell and at 15 by Jacob Tierney) seems to have been born in the late 20s or early 30s. So neither novelist nor filmmaker can be said to be reproducing his own childhood precisely. (This is also the case in Distant Voices, Still Lives, where none of the characters corresponds to Davies in terms of age.)

Being two years older than Davies and having grown up only a state away from Georgia, where the movie is set and was filmed, I feel reasonably qualified to comment on the overall accuracy of Davies’s details of place and period: it’s astonishing in how many ways he gets them right. Clearly the man did his homework, though his achievement may have as much to do with taste as it does with research, because the details themselves sometimes count for less than the kind of boxes in which they’re placed — the subjective memory enclosing them. Davies’s use of ‘Scope places a frame of 50s expansiveness — a memory of mid-50s CinemaScope that Davies and I happen to share — around the late 30s and 40s details that makes them a good deal more exciting, because they become memories within memories: the late 30s and 40s as they might have been remembered by someone during the 50s.

The story, such as it is, is recounted in flashbacks by the 16-year-old narrator-hero, David, as he sits alone in a train compartment at night, looking out the window at the dark countryside; it has to do with the deterioration of his father, Frank (Denis Leary), after he loses his factory job (he becomes a wife beater), and then of his mother, Sarah (Diana Scarwid), after Frank goes overseas to fight in Italy and is killed in action (she gradually goes mad). The other family member, David’s favorite, is Aunt Mae (Rowlands), a former nightclub singer who moves in when she has nowhere else to go, though Frank thoroughly disapproves of her. David is closer to the two women than he is to Frank, which evokes the psychosexual atmosphere of Davies’s two previous features.

There are many echoes here of A Streetcar Named Desire, with Mae taking on the flamboyant, promiscuous style of Blanche Dubois and Sarah taking on her eventual madness, and Frank becoming a brute like Stanley Kowalski. (These echoes are fully present in the novel.) Perhaps an equivalent influence on Davies is the movie The Night of the Hunter and its arsenal of neoprimitive, childlike imagery and rural, homespun folk poetry — its starry skies and oversized moon, its troubled Christianity, its lyricized and almost generic treatment of madness, its period street scenes that remind you of magazine ads for hair tonic and talcum powder.

So much for story and characters, which ultimately count for little here beyond a pretext for generating luminous scenes and moments — among others, Rowlands singing “My Romance” and “How Long Has This Been Going On?” (imperfectly but very potently) with a jazz combo; Frank and David attending a Ku Klux Klan rally (a brief scene with no counterpart in the novel, and one of Davies’s more inspired additions); the whole family attending a revival meeting (a beautifully realized sequence, including the moment when evangelist Bobbie Lee Taylor, played by Leo Burmester, briefly surveys the audience and murmurs, “Good crowd, good money”); the first genuinely artistic use of morphing I’ve seen (which has David growing from age 10 to 15 in a matter of seconds); a bunch of graduating junior high students singing “Dixie” exactly the way you’d expect them to; and the film’s gorgeous concluding shot of a train crossing the countryside in early dawn, framed against an enormous sky of varying gradations of blue, gray, orange, and pink — an extended shot that actually occasioned some walkouts by journalists at Cannes, one of whom said to me, “I get the point already.”

If “getting the point” — which I assume means the narrative point — of certain shots is your main reason for sitting through them, I suspect The Neon Bible isn’t going to be your cup of tea. Davies doesn’t offer a cinema of plot or a cinema of ideas, but a cinema of raw feelings and incandescent moments that wash over you like waves. You might find some of these waves boring if you assume that each one has to make a separate point to justify its existence. Theoretically, I suppose one could turn off a recording of a performance by John Coltrane for the same reason; if you’re not hypnotized by and ultimately grateful for the bounty that’s being delivered, you’re probably better off somewhere else.

When a friend and fellow film buff once insisted to me that Terrence Malick’s 1978 Days of Heaven was a great film, I skeptically asked her why — acknowledging that Malick’s only previous feature, Badlands (1973), was an awesome achievement, but feeling that its successor was patchy at best. Her only explanation was to cite a single shot that occurs quite early in the film: Linda (Linda Manz), the narrator, is fleeing the industrial inferno of 1916 Chicago with her older brother and his girlfriend (Richard Gere and Brooke Adams). We briefly see the three of them running toward a train in a railway yard to the sound of guitar music, and Linda says offscreen, “In fact all three of us been goin’ places, lookin’ for things, searchin’ for things…” She pauses and there’s a sudden cut to an astonishingly beautiful shot of a train in the distance against a cloud-strewn sky, moving from right to left over an elevated bridge, trailing plumes of black smoke. Linda continues, “…goin’ on adventures.”

The shock of that cut and the sublime, lyrical jolt it gives the movie as a whole — a jolt that’s at once musical and painterly in its precise articulation — may or may not suffice to make Days of Heaven great (and it isn’t the only remarkable shot by any means). Still, it’s easy to see what my friend meant. Take Apollo 13, Leaving Las Vegas, Dead Man Walking, and six others of this year’s Oscar winners, and I doubt you’ll find a hint of that kind of aesthetic liftoff anywhere. There are many such fleeting poetic moments in The Neon Bible — moments so ecstatic that you may feel yourself rising off your seat. And if much of the rest of the movie tends to be clunky as narrative, that’s a small price to pay for pieces of enlightenment you can happily carry around inside your head for months.

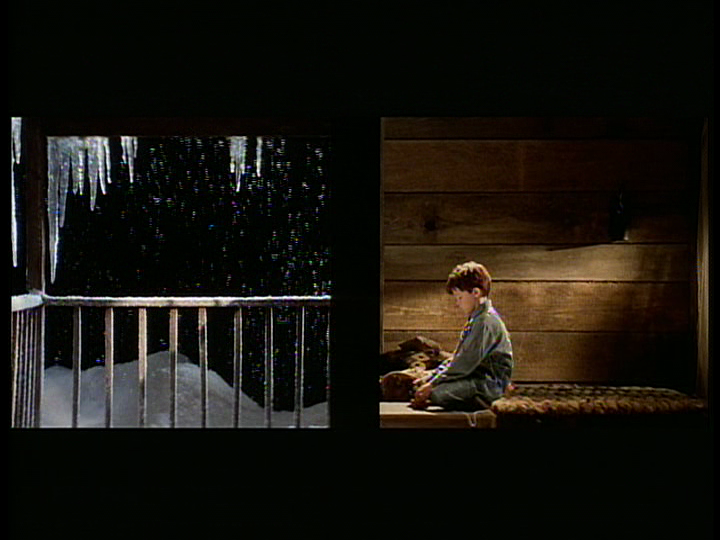

The first such epiphany occurs quite early in the movie — as early as that shot of the train in Days of Heaven — when David says, “There was no snow — no, not that year.” As he delivers the line, the ‘Scope frame becomes a diptych: on the left is an empty porch topped by icicles framing an enchanted snowfall, all clean verticals and horizontals; on the right is a lit interior where ten-year-old David is playing on the floor, all fuzzy warmth and roundness. These two images combine with David’s narration to produce a single jolt that calls to mind the hallucinatory effect of a Joseph Cornell box, as if to prove that what this whole movie is about is what’s happening inside someone’s head. If one stops to ask whether it actually snowed that year, the power of the jolt contained in that shot — combining objective and subjective experience in a manner that defies analysis — is to verify that yes, it did, and no, it didn’t. (Indeed, part of the power inherent in any Cornell box as a surrealist construction rests in the primitive, obsessive fetishism that decrees that every treasured object becomes at once totemic and sacred in its fresh context.)

In another such moment in The Neon Bible — one that’s no less mysterious — the camera slowly approaches a large white bedsheet hanging on a clothesline until the wind-rippled sheet fills the entire ‘Scope frame, while all that one hears on the sound track is the opening theme music of Gone With the Wind. My description of this moment, like my descriptions of the other magically charged and highly condensed film moments above, can give you no sense whatever of the emotional power it carries — though if the concept behind it mattered more than its realization it probably wouldn’t register as strongly. As long as Davies delivers such moments, I couldn’t care less how adept he is at telling stories –j ust as I don’t care whether Gena Rowlands can carry a tune. As LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka wrote in the 60s, defending John Coltrane against charges of being undisciplined, “It’s like calling Sonny Liston a sloppy boxer. It won’t get you anywhere. Because you have to make the remark from a prone position.”