- From the Chicago Reader (November 27, 1998), and reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema and on the BFI Blu-ray of the film. In his audiovisual essay on the latter release, Geoff Andrew rightly corrects my error, below, of describing the ax murder victim as Demy’s Lola, not von Sternberg’s Lola Lola. — J.R.

The Young Girls of Rochefort

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jacques Demy

With Catherine Deneuve, Françoise Dorléac, George Chakiris, Gene Kelly, Danielle Darrieux, Michel Piccoli, Grover Dale, Jacques Perrin, Geneviève Thénier, Henri Crémieux, and Jacques Riberolles.

As eccentric as this may sound, Jacques Demy’s 1967 Les demoiselles de Rochefort is my favorite musical. Yet despite my 30-year addiction to the two-record sound track, the first time I was able to see the movie subtitled was a couple of weeks ago — helpful considering my faltering French. It’s certainly the odd musical out in terms of both its singularity and its North American reputation — a large-scale tribute to Hollywood musicals shot exclusively in Rochefort in southwest France, and an unabashedly romantic paean to American energy and optimism that’s quintessentially French. It has a score by Michel Legrand that’s easily his best, offering an almost continuous succession of songs with lyrics by Demy, all written in alexandrines (as is a climactic dinner scene that’s spoken rather than sung); choreography that ranges from mediocre (Norman Maen’s frenchified imitations of Jerome Robbins) to sublime (Gene Kelly’s choreography of his own numbers); and perhaps the most beautiful dovetailing of failed and achieved connections apart from Shakespeare and Jacques Tati’s Playtime, shot during the same period. Read more

From Framework (volume 45, number 1, Spring 2004). Because of its length, I’m running this in two parts. — J.R.

This interview took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, April 20, 2002 — if memory serves, at the Abasto shopping mall, where the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film was then being held.

NK: How did you come to film criticism and film journalism? You start out in the States and have some years in Paris and then London and then back to the States.

JR: Like most other film critics of my generation I didn’t set out to be a film critic. I was a writer from very early on and my family was involved in the film business but my initial interest was in being a fiction writer. I wrote fiction in high school and in college and was hoping, very unrealistically, to have a career as a novelist.

NK: The fiction writer aspect survives into the opening page of Moving Places where you riff on the opening of William Faulkner’s Light in August.

JR: My MA thesis was on Light in August. At the time I got fed up and quit graduate school I was working on a novel and somebody I knew from college offered me a job editing a collection of film criticism. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 1, 1989).

It’s hard to say what Terence Davies’s powerful masterpiece is about — growing up in a working-class family in Liverpool in the 40s and 50s — without making it sound familiar and lugubrious. In fact, this beautiful memoir, conceivably one of the greatest of all English films, is so startling and original that we may not have the vocabulary to do it justice. Organized achronologically, so that events are perceived more in terms of emotional continuity than of narrative progression, the film concentrates on family events like weddings and funerals and on songs sung at parties and the local pub. It’s clear that Davies’s childhood, which was lorded over by a brutal and tyrannical father, was not an easy one, yet the delight shown and conveyed by the well-known songs makes the experience of this film cathartic and hopeful as well as sorrowful and tragic. (There are some wonderful laughs as well.) Much of the film emphasizes the bonds between the women in the family and their female friends, although there’s nothing doctrinal or polemical about its vision, and the purity and intensity of its emotional thrust are such that all the characters are treated with passion and understanding. Read more

From the December 22, 2000 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

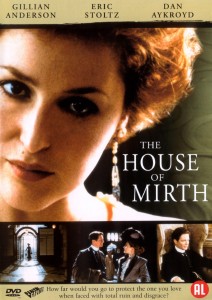

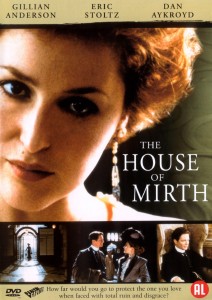

“If she slipped she recovered her footing, and it was only afterward that she was aware of having recovered it each time on a slightly lower level.” Edith Wharton’s encapsulation of the narrative form of her tragic (and sexy) 1905 novel, describing the progressive defeat of socialite Lily Bart by the ugly indifference of Wharton’s own leisure class, is given an extra touch of Catholic doom in Terence Davies’s passionate, scrupulous, and personal adaptation, which to a surprising degree preserves the moral complexity of most of the major characters. It’s regrettable if understandable that the Jewishness of social climber Sim Rosedale (Anthony LaPaglia) is no longer an issue, and Lawrence Selden, Lily’s confidante, is somewhat softened by a miscast Eric Stoltz, but the cast as a whole is astonishing — especially Gillian Anderson as Lily and Dan Aykroyd in his finest performance to date. Davies feels and understands the story thoroughly, giving it a raw emotional immediacy that would be unthinkable in the shopper-friendly adaptations of Merchant-Ivory and their imitators, and the film’s feeling for decor and costumes, derived from both John Singer Sargent paintings and Orson Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons, is exquisite. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 5, 1996). — J.R.

The Neon Bible

Directed and written by Terence Davies

With Gena Rowlands, Diana Scarwid, Jacob Tierney, Denis Leary, Leo Burmester, Frances Conroy, and Peter McRobbie.

Two paradoxical facts about Terence Davies’s first film adaptation:

(1) It follows fairly closely The Neon Bible, a novel written by John Kennedy Toole for a literary contest in the mid-50s, when he was 16 — a decade before he finished work on his second novel, A Confederacy of Dunces, and about 15 years before he, still unpublished, committed suicide (A Confederacy of Dunces was published ten years later, The Neon Bible ten years after that). I don’t care much for The Neon Bible, a hackneyed mood piece set in a rural backwater of the deep south, but I think the movie, which seems 100 percent Davies, is wonderful.

(2) Of all the English-speaking films shown at Cannes last May, the two that got the most boorish and least comprehending reception by the English-speaking press were The Neon Bible and Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, though for nearly opposite reasons. Jarmusch, who’s long been criticized for coasting along in Down by Law, Mystery Train, and Night on Earth on the same kind of hip humor he virtually invented for Stranger Than Paradise, finally broke free and did something bold, original, political, dark, scary, outspoken, witty, and often beautiful — a black-and-white western that should be opening here sometime next month. Read more

From Framework (volume 45, number 1, Spring 2004). Because of its length, I’m running this in two parts. — J.R.

This interview took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, April 20, 2002 — if memory serves, at the Abasto shopping mall, where the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film was then being held.

NK: In Movie Wars you are very critical of aspects of the U.S. movie business, and in an earlier autobiographical book, Moving Places, you explain that your family was involved in film exhibition. So when you make your criticisms of the way the movie business works now you do so from apposition of informed, long-term historical knowledge. What do you think the main, deleterious effects are?

JR: The thing that is important to make clear at the outset is that film exhibition is radically different from when I was growing up in the movie business. It could be argued by people currently working in the business that it’s very easy for me to make my criticisms because I’m not actually running the business the way they are. But on the other hand I don’t know if everything can or should be reduced to matters of business. And I think that’s part of the problem now, the belief that it’s totally a business and shouldn’t be anything else. Read more