From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1993). — J.R.

Probably John Boorman’s most underrated film — an impossibly ambitious and pretentious but also highly inventive, provocative, and visually striking SF adventure with metaphysical trimmings (1974). Set in a postapocalyptic society in 2293, it stars Sean Connery as a warrior and noble savage with dawning awareness; interestingly enough, the plot in many ways resembles that of Boorman’s best film, Point Blank. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 3, 1998). — J.R.

A department store clerk (Clara Bow) tries to live according to the tenets of Elinor Glyn’s book about sex appeal (also titled It) and winds up marrying her boss. This fast and funny silent comedy of 1927 has one of the great lines of the period — “Hot socks! Here comes the boss!” — and as Dave Kehr has pointed out, it “launched Clara Bow as a star of extraordinary dimensions (most of them around the hips).” Directed by Clarence Badger, with Antonio Moreno, William Austin, Jacqueline Gadsdon, a young Gary Cooper, and Glyn herself, who worked on the script with Hope Loring and Louis D. Lighton. A real treat. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 1, 1990). — J.R.

The greatness of Carl Dreyer’s first sound film (1932, 82 min.) derives partly from its handling of the vampire theme in terms of sexuality and eroticism and partly from its highly distinctive, dreamy look, but it also has something to do with Dreyer’s radical recasting of narrative form. While never less than mesmerizing, it confounds conventions for establishing point of view and continuity, inventing a narrative language all its own. Some of the moods and images are truly uncanny: the long voyage of a coffin, from the apparent viewpoint of the corpse inside; a dance of ghostly shadows inside a barn; a female vampire’s expression of carnal desire for her fragile sister. The remarkable sound track, created entirely in a studio (in contrast to the images, all filmed on location), is an essential part of the film’s voluptuous, haunting otherworldliness. It was originally released by Dreyer in four separate versions — French, English, German, and Danish; most prints now contain portions of two or three of these versions, although the dialogue is pretty sparse.) (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Sight and Sound (Summer 1977). -– J.R.

THE MAJOR FILM THEORIES: AN INTRODUCTION

By J. Dudley Andrew

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, £2.50(paperback)

The widespread distrust of film theory still persisting in mainstream criticism is scarcely confined to Anglo-American film culture. Less than a decade back, when Noël Burch’s Praxis du cinéma -– later translated as Theory of Film Practice –- first appeared in France, someone at Gallimard hit on a rather demented sales pitch, and the book was marketed with a wraparound banner boldly proclaiming, ‘Contre toute théorie.’ The curious science fiction tone of this declaration highlights a subterranean bias which informs most film reviewing on and off the continent: the idea that theory is an option best left to dusty academicians, while everyone else is better off operating on free-floating intelligence and intuition. Ironically, this is an assumption which expresses a theory of its own: that knowledge is essentially empirical. And the definition accorded to ’empiricist’ by the Concise Oxford may be worth at least considering:'(person) relying solely on experiment; quack.’

In all fairness to ‘anti-theorists’, it should be conceded that science and art are hardly the same thing. If a sizeable part of our knowledge of the former is grounded in theory, the parti pris underlying our knowledge of cinema tends to be a much more random affair, a generally murky blend of half-examined predilections and working hypotheses. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 23, 1987). — J.R.

Genre specialist John Carpenter returns to the principle of confined space that he used as a disciplinary structure in Assault on Precinct 13 and The Thing in this horror thriller set in an abandoned church. The main difference here from earlier Carpenter films is the heavy metaphysical baggage: a team of graduate students and teachers (including Lisa Blount, Victor Wong, and Jameson Parker) in physics and science is summoned by a Catholic priest (Donald Pleasence) to study an ancient religious manuscript that proves to contain differential equations (long before such equations were developed), and a canister containing a green liquid that proves to be seven million years old. Mathematics combines with demonology to produce a variant on Night of the Living Dead, and while the church is playfully called Saint Godard’s, the pivotal use and significance of mirrors spawned by the canister liquid might make Saint Cocteau’s a more appropriate appellation. While the dense significations of the script (credited to one “Martin Quatermass”) may get a bit thick in spots, Carpenter’s handsome ‘Scope images generally make the most of them, and some haunting poetic notions — such as video images from the future that appear as recurring dreams dreamt by the church’s inhabitants — figure effectively in the plot. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1988). — J.R.

D.W. Griffith’s last film (1931) was unquestionably dated when it was released at the height of the Depression, both as an antidrinking polemic — probably fueled in part by Griffith’s own struggles with alcoholism — and as a Victorian melodrama. Yet today it emerges as one of his most powerful and intensely felt works — not merely a heartbreaking story and a portrait of the Depression at its grimmest, but a poignant summary of everything that Griffith could do with a camera, even in low-budget, unspectacular circumstances. With Hal Skelly and Zita Johann. 87 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 27, 2004). — J.R.

The Blonds

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Albertina Carri

With Analia Couceyro.

Rosenstrasse

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Margarethe von Trotta

Written by Pamela Katz and von Trotta

With Katja Riemann, Maria Schrader, Martin Feifel, Jurgen Vogel, Jutta Lampe, Doris Schade, and Fedja van Huet.

It was a severe disappointment, Beyle [Stendhal] writes, when some years ago, looking through old papers, he came across an engraving entitled Prospetto d’Ivrea and was obliged to concede that his recollected picture of the town in the evening sun was nothing but a copy of that very engraving. This being so, Beyle’s advice is not to purchase engravings of fine views and prospects seen on one’s travels, since before very long they will displace our memories completely, indeed one might say they destroy them. — W.G. Sebald, Vertigo

I don’t know if some memories are real or if they’re my sisters’. –Albertina Carri in The Blonds

When I was in junior high school in the 50s I associated Stanley Kramer’s name — first as a producer, then as a producer-director — with offbeat, somewhat worthy highbrow ventures such as Cyrano de Bergerac, Death of a Salesman, High Noon, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. Read more

This appeared Cinema Scope no. 11 (summer 2002).Thanks to Francois Thomas in helping me clean up my German and French. — J.R.

“You can’t smell email,” Raúl Ruiz insisted to me the night before we had this interview at the 2002 Rotterdam Film Festival, explaining to me why he didn’t have any truck with the Internet. He added that lately he’s been collecting various first editions, excommunications, and death sentences, many of them from the 19th century and earlier, and he can smell all of them.

At first I was surprised by this old-fashioned form of resistance, but then the more I thought about it, the more I realized that Raúl is basically a 19th century figure. His largely Borgesian canon of 19th and early 20th century English and American writers (Chesterton, Stevenson, Wells, Harte, Hawthorne, Melville, et al) and his taste for rambling narratives and tales within tales smacks of a Victorian temperament.

I first encountered Ruiz’s work during my first trip to the Rotterdam Film Festival, in 1983, and it was there where we first became friends three years later —- as well as where we had this interview on January 26, in the lobby of the hotel where we were both staying. Read more

From the Autumn 1984 Film Quarterly. I reviewed this book at Biskind’s request, and my position was hampered by the fact that he was the main editor of American Film at the time, where his commissions were essential to my livelihood. Our relationship became even more strained after I was all set to review the book and he then informed me that he wished I weren’t reviewing it. — J.R.

SEEING IS BELIEVING: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties By Peter Biskind. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983. $22.95 cloth, $10.95 paper.

The first thing to be said about Peter Biskind’s ambitious and long-awaited study of ideology in Hollywood movies of the fifties is that it can’t be dipped into at random with out a considerable amount of confusion setting in. Without the benefit of Biskind’s careful construction and preparation, the unwary reader who plunges in midstream is bound to be bewildered or dismayed by many of the political labels, whereby Thieves Highway, for instance, is designated as a “right-wing film,” or High Noon and The Blob as “radical films.” Even in the Introduction, which tends to be more cautious than the rest of the book, several eyebrows are likely to be raised by the following sentence: “The films of Robert Aldrich can usually be counted on to be somewhere on the left, just as the films of Elia Kazan are frequently in the middle, while those of John Ford are to the right of his and those of Alfred Hitchcock are to the right of his. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 8, 1994). Also reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

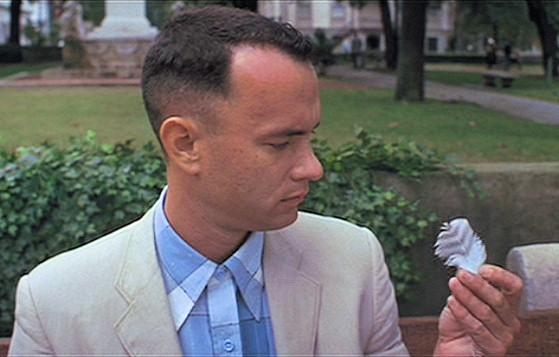

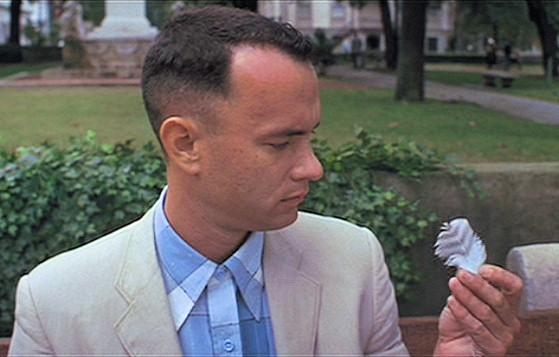

** FORREST GUMP (Worth seeing)

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by Eric Roth

With Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, Sally Field, Michael Humphreys, and Hanna Hall.

In the opening shot of Forrest Gump — a movie that might be described as Robert Zemeckis’s flag-waving Oscar bid — the camera meticulously follows the drifting, wayward trajectory of a white feather all the way from the heavens to the ground, just beside the muddy tennis shoes of the title hero (Tom Hanks). Forrest Gump, a slow-witted, sweet-tempered, straight-shooting fellow from Alabama with an IQ of 75, is waiting for a bus in a small park in Savannah, Georgia. Picking up the feather and placing it inside a book, he proceeds to recount his life story to various passing strangers; in the film’s final shot, over two hours later, we see a breeze carry the same white feather up and away.

These framing shots — a poetic statement about the vicissitudes of chance, how histories are made, unmade, and remade — are meant to say something about a half-century of American life, from the 40s to the present; and the tragicomic life of Forrest Gump, a saintly fool, is meant to embody those years. Read more

Written to introduce a dossier in Farsi on Alain Resnais prepared by Ehsan Khoshbakht in March 2012. — J.R.

Alain Resnais is clearly one of our greatest living filmmakers. But he’s also one of the most elusive, for a number of reasons. He started out as the most international of all the French New Wave artists, at least in his early features (especially Hiroshima mon amour,Last Year at Marienbad, La Guerre est finie,Je t’aime, je t’aime, and Providence), but then went on to become the most French of French directors (not only in obvious cases such as Mon oncle d’Amérique, Stavisky…, Mélo, Same Old Song, Not on the Lips, and Wild Grass, but even in films derived from English or partially American sources, such as I Want To Go Home, Smoking, No Smoking, and Private Fears in Public Places). Even before he got around to making features, he made by far the greatest films in the history of cinema about racism and colonialism (Statues Also Die), the Holocaust (Night and Fog), plastic (La Chant du Styrène), and libraries (Tout la mémoire du monde).Among Read more

Commissioned by Stanley Schtinter in the summer of 2019 for the limited LP release of Carles Santos’ soundtrack score for Pere Portabella’s Vampir Cuadecuc in early 2020. I received a copy of this LP from Stanley earlier that month — on the final day of a Portabella retrospective in London that began in November, when I gave a lecture at Close-up and Portabella himself, who’d just turned 93, was amiably present. — J.R.

Masterpieces have many possible ports of entry. My own passport into Pere Portabella’s Vampir Cuadecuc (1970) — first seen multiple times at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes in 1971 and then celebrated in my festival coverage for the Village Voice — was composed of rampant cinephilia crossed with political ignorance, as well as a fascination with William S. Burroughs’ use of cut-ups in Naked Lunch (1959), The Soft Machine (1961-1966), and The Ticket That Exploded (1962-1967) to create scrambled syntax (echoed in Portabella’s capacity to shift his narrative focus within single shots from the Dracula story itself to the filming of it). I knew then that Portabella, one of the Spanish producers of Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, had his own passport confiscated as punishment by Francoist Spain, accounting for his absence in Cannes, and that his film was mostly a silent documentary of the shooting of an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula by one Jesus Franco, accompanied by musique concrète. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 2, 2004). — J.R.

I don’t have much patience with colleagues who dismiss Charlie Chaplin by saying that Buster Keaton was better (whatever that means). To the best of my knowledge, with the arguable exception of Dickens, no one else in the history of art has shown us in greater detail what it means to be poor, and certainly no one else in the history of movies has played to a more diverse audience or evolved more ambitiously from one feature to the next. The recent European release of his eight major features on DVD, digitally restored and with superb bonus materials, has been matched over here by only four titles so far, including Modern Times (1936), the second of his two Depression-era masterpieces — though viewing it on a big screen is required for maximal impact. The opening sequence of the Tramp on the assembly line is possibly his greatest slapstick encounter with the 20th century, and as Belgian filmmakers Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne brilliantly observe on one of the DVD extras, the famous shot of his being run through machinery equates him with a strip of film. Still, there’s more hope here than in City Lights, perhaps because this time the Tramp has Paulette Goddard, another plucky urchin, to keep him company. Read more

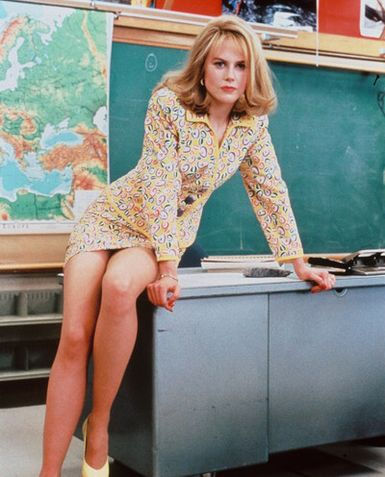

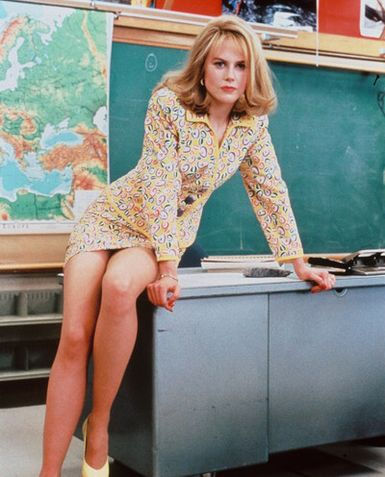

From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 1995); slightly tweaked in late 2013. — J.R.

If, like me, you find things to admire in many of Gus Van Sant’s films, you may be especially gratified by what he’s done with this satirical anti-TV script by Buck Henry — suggested by a real-life crime and adapted from a Joyce Maynard novel — and a spot-on performance by Nicole Kidman that may be the best of its kind since Tuesday Weld’s wicked sexual turns in Pretty Poison and Lord Love a Duck. Charting the ruthlessness of an ambitious bimbo telecaster in Little Hope, New Hampshire, this staccato black comedy sustains its brilliant exposition and narration until the plot turns to premeditated murder, complete with hapless and semicoherent teenage accomplices. The movie loses much of its pitch and many of its laughs at this juncture, and there’s an uncomfortable tendency to equate the falsity and venality of TV too exclusively with Kidman’s character, thereby bypassing golden opportunities offered by Wayne Knight (as a station boss) and an uncredited George Segal to make the target less gender specific. But much of this is good nasty fun, with a fine secondary cast that includes Matt Dillon, Joaquin Phoenix, Alison Folland, Casey Affleck, Illeana Douglas, and Dan Hedaya; also look for striking cameos by David Cronenberg and screenwriter Buck Henry. Read more

If, like me, you find things to admire in many of Gus Van Sant’s films, you may be especially gratified by what he’s done with this satirical anti-TV script by Buck Henry — suggested by a real-life crime and adapted from a Joyce Maynard novel — and a spot-on performance by Nicole Kidman that may be the best of its kind since Tuesday Weld’s wicked sexual turns in Pretty Poison and Lord Love a Duck. Charting the ruthlessness of an ambitious bimbo telecaster in Little Hope, New Hampshire, this staccato black comedy sustains its brilliant exposition and narration until the plot turns to premeditated murder, complete with hapless and semicoherent teenage accomplices. The movie loses much of its pitch and many of its laughs at this juncture, and there’s an uncomfortable tendency to equate the falsity and venality of TV too exclusively with Kidman’s character, thereby bypassing golden opportunities offered by Wayne Knight (as a station boss) and an uncredited George Segal to make the target less gender specific. But much of this is good nasty fun, with a fine secondary cast that includes Matt Dillon, Joaquin Phoenix, Alison Folland, Casey Affleck, Illeana Douglas, and Dan Hedaya; also look for striking cameos by David Cronenberg and screenwriter Buck Henry. Read more

Commissioned by The Chiseler, and posted there on July 4, 2020. — J.R.

My first encounter with Werner Herzog was at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 1973, where I first saw Aguirre, the Wrath of God in an English-dubbed version that included, if memory serves, a few Brooklyn accents in 16th century Peru. (This is why it took some rethinking and retooling before the film could be successfully exhibited in the U.S., in German with subtitles.) But what flummoxed me the most — in spite of the film’s awesome visual splendor and its crazed poetic conceits — was what Herzog revealed about the opening intertitle when I asked him about it during the Q & A.

The intertitle: “After the conquest and sack of the Incan empire by Spain, the Indians invented the legend of El Dorado, a land of gold, located in the swamps of the Amazon tributaries. A large expedition of Spanish adventurers led by Pizarro sets off from the Peruvian sierras in late 1560. The only document to survive from this lost expedition is the diary of the monk Gaspar de Carvajal.” Herzog’s cheerful admission: the bit about the document and the diary was a total lie, invented by him because he reasoned that people wouldn’t accept the film’s premises otherwise. Read more

If, like me, you find things to admire in many of Gus Van Sant’s films, you may be especially gratified by what he’s done with this satirical anti-TV script by Buck Henry — suggested by a real-life crime and adapted from a Joyce Maynard novel — and a spot-on performance by Nicole Kidman that may be the best of its kind since Tuesday Weld’s wicked sexual turns in Pretty Poison and Lord Love a Duck. Charting the ruthlessness of an ambitious bimbo telecaster in Little Hope, New Hampshire, this staccato black comedy sustains its brilliant exposition and narration until the plot turns to premeditated murder, complete with hapless and semicoherent teenage accomplices. The movie loses much of its pitch and many of its laughs at this juncture, and there’s an uncomfortable tendency to equate the falsity and venality of TV too exclusively with Kidman’s character, thereby bypassing golden opportunities offered by Wayne Knight (as a station boss) and an uncredited George Segal to make the target less gender specific. But much of this is good nasty fun, with a fine secondary cast that includes Matt Dillon, Joaquin Phoenix, Alison Folland, Casey Affleck, Illeana Douglas, and Dan Hedaya; also look for striking cameos by David Cronenberg and screenwriter Buck Henry.

If, like me, you find things to admire in many of Gus Van Sant’s films, you may be especially gratified by what he’s done with this satirical anti-TV script by Buck Henry — suggested by a real-life crime and adapted from a Joyce Maynard novel — and a spot-on performance by Nicole Kidman that may be the best of its kind since Tuesday Weld’s wicked sexual turns in Pretty Poison and Lord Love a Duck. Charting the ruthlessness of an ambitious bimbo telecaster in Little Hope, New Hampshire, this staccato black comedy sustains its brilliant exposition and narration until the plot turns to premeditated murder, complete with hapless and semicoherent teenage accomplices. The movie loses much of its pitch and many of its laughs at this juncture, and there’s an uncomfortable tendency to equate the falsity and venality of TV too exclusively with Kidman’s character, thereby bypassing golden opportunities offered by Wayne Knight (as a station boss) and an uncredited George Segal to make the target less gender specific. But much of this is good nasty fun, with a fine secondary cast that includes Matt Dillon, Joaquin Phoenix, Alison Folland, Casey Affleck, Illeana Douglas, and Dan Hedaya; also look for striking cameos by David Cronenberg and screenwriter Buck Henry.