From Framework (volume 45, number 1, Spring 2004). Because of its length, I’m running this in two parts. — J.R.

This interview took place in Buenos Aires, Argentina, April 20, 2002 — if memory serves, at the Abasto shopping mall, where the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film was then being held.

NK: In Movie Wars you are very critical of aspects of the U.S. movie business, and in an earlier autobiographical book, Moving Places, you explain that your family was involved in film exhibition. So when you make your criticisms of the way the movie business works now you do so from apposition of informed, long-term historical knowledge. What do you think the main, deleterious effects are?

JR: The thing that is important to make clear at the outset is that film exhibition is radically different from when I was growing up in the movie business. It could be argued by people currently working in the business that it’s very easy for me to make my criticisms because I’m not actually running the business the way they are. But on the other hand I don’t know if everything can or should be reduced to matters of business. And I think that’s part of the problem now, the belief that it’s totally a business and shouldn’t be anything else.

NK: Has Miramax ever responded to your criticisms of them, as given in Movie Wars and also in your book on Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man?

JR: I’ve had no response whatsoever from Miramax, either because I don’t exist for them, I’m not considered important enough, or because it’s just not their style to respond. But when they were getting ready to release the DVD of Dead Man they asked Jarmusch who might be able to do a commentary and he must have mentioned me, because they called me up and asked if I would like to do the commentary. I asked whether any payment would be involved, they said no, and also said it had to be done immediately.

So I declined and suggested Greil Marcus. They wound up not having any commentary. Anyway, I think it’s safe to say that there’s been no feedback from Miramax.

Ray Privett in a piece in Cinema Scope said my claim — actually the claim of a curator I quoted — that Miramax destroyed all the American prints of Through the Olive Trees wasn’t true because in fact someone had requested a print of that film and did receive one, so they haven’t destroyed all the prints. I think it often depends on who you get on the phone. What happens with Miramax is often very haphazard. Films will be press-screened in Chicago and we find out that whatever was going to be the opening date has been changed, they’ve decided to open it six months later, or not open it at all.

So as a reviewer it’s very difficult to deal with Miramax’s films because one is constantly being manipulated in certain ways. Sometimes they show a film simply to see if people like it, and then take it back afterwards and re-cut it, but they still call it a press screening, so you’re always one step behind them.

NK: Could you say something about how you came to be a consultant on the re-editing of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil? Did that follow on from your piece in Film Quarterly (vol. 46, no. 1, Fall 1992)?

JR: The Film Quarterly piece came from my editing of the Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich book, This is Orson Welles. It was an outtake from that. The memo was initially part of the book, until the editor at Harper Collins said the book was too long and we had to cut it. So I asked Oja Kodar if we could publish it elsewhere.

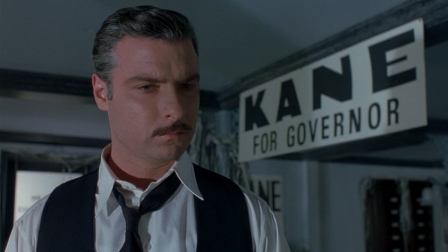

Here, it’s worth pointing out -– because people are shocked to hear this, and they should know about it –- that before Film Quarterly agreed to publish that piece it was rejected by Film Comment and by Premiere. The then-editor of Film Comment, Richard T. Jameson, wasn’t even interested in reading the piece before deciding. He said, ‘We’ve done too much on Welles lately’, and yet he later wound up publishing a general piece on Welles and Touch of Evil and The Third Man around the time the memo came out in Film Quarterly. I was a little shocked by that because there was a Welles conference in Munich that showed a lot of restorations of his films, a lot of things that had never been seen before, and I asked if I could write about them in Film Comment and once again, there was no interest. And this was at the same time they were publishing things on a made-for-TV movie about the making of Citizen Kane.

NK: That would have been the HBO miniseries/film RKO 281, executive produced by Ridley and Tom Scott and directed by Benjamin Ross. I haven’t seen it.

JR: Even though Film Comment will write about films that don’t have distributors, it’s still very geared to the film market, and if there’s this new Orson Welles work shown in Europe that doesn’t have a distributor, they don’t want to hear about it. At least that’s the only explanation for their lack of interest that I can think of. But I don’t want to come across as a strong disparager of Film Comment. I’m an occasional contributor and I’d like to have written for them more than I have over the last few years. I think they’re an important resource. But the problem is more endemic than just one film magazine. In Movie Wars the chapter that came from work previously published in Trafic was heavily cut by my editor at a cappella Press, and the reason given was that there were too many films he hadn’t heard of. That shocked me because it wouldn’t have occurred to anyone at Trafic to use that as an argument – and there were a great many films they hadn’t heard of in France. [2013 afterthought: I may have been exaggerating a little bit here. Subsequently, I was asked in another piece for Trafic to explain who Jan Troell was.] I think there’s a general mentality in the States that’s based on a notion of market flow and consumption, a form of thinking that believes if people can’t immediately purchase something then it would be better for them not to know that it exists. (to be continued)