A chapter from Film: The Front Line 1983. — J.R.

Born in Konstanz, Germany, 1942.

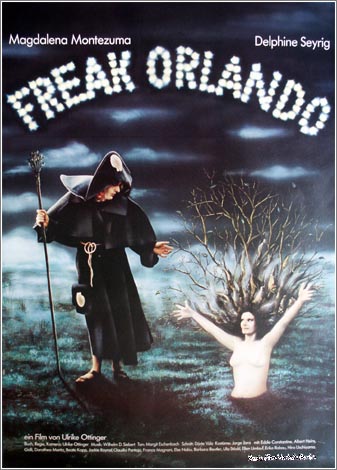

What do I know about Ulrike Ottinger? Not much, but enough to make me want to know more. Admittedly, I’ve seen only her last two features. And on the basis of a single viewing about a year ago, Freak Orlando is a decidedly uneven film, definitely hit-or-miss in its overall thrust, and conceivably full of as many misses as hits. Like it or not, though, the film can be regarded as a kind of climactic summa of the performance-oriented European avant-garde film, from Carmelo Bene to Philippe Garrel to Marc’O to the collaborations of Pedro Portbella* to Christopher Lee — to cite the names of four leading figures of excitement and interest in this category whose careers I lost track of after moving back to the U.S. from Europe in 1977. Insofar as Freak Orlando can be regarded as the Monterey Pop or Woodstock of the European avant-garde performance movement, it’s a valuable and fascinating document to have, and one therefore has reason to look forward to its release in this country…Ticket of No Return, on the other hand, strikes me as a fully achieved work — one of the few true masterpieces of the contemporary German avant-garde cinema — making Ottinger an obligatory inclusion for this book.

(Footnote: *Portabella actually belongs to a somewhat more modernist and politically beleaguered than the others, and his remarkable black-and-white Vampyr and Umbracle, both made in Franco Spain, which I reviewed in my Cannes coverage for the Village Voice — June 17, 1971 and June 29, 1972, respectively — owe a considerable amount of their own brilliance to the soundtrack constructions of composer Carlos Santos. [A 2012 footnote to this footnote: The fact that the Catalan language was outlawed in Franco Spain meant that Pere Portabella was then known to me as Pedro, Carles as Carlos, and Vampir – Cuadecuc only as Vampir or Vampyr.]

First, though, here’s a little bit about the films I don’t know, as gleaned from Roswitha Müller’s valuable interview with Ottinger in Discourse (No. 4, Winter 1981/82). Laokoon was made with a lot of difficulty over a two-year period. (Ottinger: “I am a painter originally. The people who sold my paintings found my new medium interesting and made it possible to raise the 20,000 marks necessary to make this first film. . .the difficulties involved in editing seemed insurmountable at times.”) And her second film, The lnfatuation of the Blue Sailors, was made in Berlin: “It is a free association of images to the texts by Apollinaire which themselves are written in the form of a collage. I have also tried to let the texts which satirize the Comédie Française, as well as the concierge from Marseille, speak for me.”

Madame X, her third film (and the longest to date), reportedly as variable a work as Freak Orlando, was financed by money from ZDF (German TV). From most accounts, including Ottinger’s, it appears to be her most explicitly feminist work so far. (“The leitmotif throughout the film is about the prohibition imposed on women to make their own experiences”), and it includes a cameo appearance by Yvonne Rainer — in Germany at the time because of the DAAD (German Foreign Exchange Services) — on roller skates, delivering a monologue written by Rainer herself.

Ticket of No Return somehow manages to.be two things at once: (1) an inspired development and fusion of many of the most fruitful currents in European film over the past several years — combining elements in everything from Vera Chytilova to Federico Fellini to Lothar Lambert to Jacques Rivette to Werner Schroeter to Jacques Tati (a very democratic freak salad, indeed), and (2) an uncategorizable masterpiece so sui generis that influences.seem hardly relevant at all to the synthesis achieved.

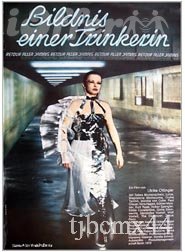

The nameless heroine — played by Tabea Blumenschein, a real-life clothes designer who dreamed up, designed, and made all the extravagant outfits in the film — arrives in Berlin on a one-way ticket; in the opening shot, she walks awav from the camera, her bright red skirt receding like the title heroine’s yellow purse in the opening shot of Hitchcock’s Marnie, to Felliniesque music on the soundtrack, in an airport that virtually announces itself as the offspring of the Orly Airport space that opens Tati’s Playtime. An off-screen female narrator commences the story, and only the heroine’s hands are visible just before the title and subtitle (Portrait of a Woman Drinker) appear on the screen. Next come the credits, with color snapshots of each crew member lovingly placed next to her or his name (the sense of chuminess in both Ottinger films I’ve seen is an essential part of their charm, making Ottinger in one sense the Howard Hawks of the feminist avant-garde). “Berlin-Tegel-Reality,” announces a female voice on the p.a. system. The heroine again walks away from the camera, this time seen from a much lower camera angle; a male dwarf passes by, just before she approaches a glass pane being washed by a female janitor. The airport doors slide open with a wheeze; three woman dressed in prim grey outfits, known as Social Question (Magdalena Montezuma), Accurate Statistics (Orpha Termin), and Common Sense (Monika Von Cube), follow the heroine out the door in another shot whose abrupt sounds and sharp, blocky movements seem to come out of the same comic repertoire as Playtime. Formally and thematically speaking, all the basic elements of the film are already present in this opening, as soon as it’s made clear that the heroine has come to Berlin to drink herself to death. The remainder of the movie is merely a celebration that decision, rendered in as many different registers and forms of celebratory pleasure as Ottinger can get onto the screen — serving up a veritable feast of depravity and irresponsibility.

ln terms of plot, then, that’s most of what Ticket of No Return has to offer: conceptually speaking, a string of episodes which repeat the same root elements, like a string of gags in a series of Road Runner cartoons (where wit always has something to do with the distinction between sameness and difference; the importance of Acme products in Chuck Jones’ conceptual schemes seems fundamental). Within this relatively static framework, however, the variables — such as the heroine’s wardrobe, the diverse narrative settings for her drinking, and diverse inventions in the dialogue and mise en scène — give the film a flamboyant, expressive range. Carrie Rickey, in an appreciative review in The Village Voice, offered an enthusiastic rundown of some of the heroine’s ensembles: “a persimmon melton overcoat and bonnet for deplaning at Berlin-Tegel airport, an Alphaville of starkness and alienation; a strapless black satin gown (reminiscent of Hayworth in Gilda) with matching opera-length gloves and oversized bow headdress, in which she chugalugs cognac at the casino; a fucshia vicuna (l kid you not) cocktail dress with rhinestone details and matching theater jacket, which she wears to a lesbian bar where she’s too drunk to boogie.” (Rickey also labeled Social Question, Accurate Statistics, and Common Sense the “Greek chorus to all of Blumenschein’s glamorous entrances…a trio clad in houndstooth…”)

Early in her travels around Berlin, the heroine stumbles upon a woman identified as Drinker from the Zoo in the credits (played by Lutze), a bag lady who goes around with a shopping cart, whom she promptly invites to accompany her as a drinking companion. (Whether it’s actually Lutze who’s washing the airport panes at the beginning is not clear to me at this point, but she’s clearly already there in spirit.) And the interesting thing about this character is that she comes from another genre of filmmaking — the documentary, according to Ottinger, although one could equally equate her with neorealism — in contrast to the more Hollywoodish styling of the heroine. And it is the scandal provided by the union between these two that provides the closest thing to a consecutive plot that Ticket of No Return can claim.

The heroine steps out in her strapless black satin gown; a yellow cab stops for her in extreme close-up (a blur of yellow crosses the screen); she takes a drink in the back seat; she sees some dwarfs. After the cab hits the bag lady in the street, forcing her to drop various things and denounce the driver, Social Question, Accurate Statistics, and Common Sense stop in an adjacent cab and prattle their disapproval. A man in an elevator shows the heroine a card trick; in the casino bar, he shows her dice tricks. After she steps away from the roulette table, ,she has a drink at the bar and breaks her glass; the bartender delivers a deadpan monologue to no one about her social behavior, dutifully repeated later in the film. On her way back to her hotel, the nameless dwarf in front of a fountain pays his respects to her.

Dressed in yellow, she drinks in a café the following day while the three grey sisters cite facts and figures at an adjoining table – and the value of these in explaining alcohol to the public – while daintily devouring ice cream sundaes. The bag lady appears on the other side of the pane, is invited in by the heroine, and is served cognac. They each throw a glass of water at the glass pane, are photographed by a couple in the café, and are thrown out on the street by the management. (On the street, the couple continue to take pictures of them.) The two women repair to the heroine’s hotel room, drink wine and talk and laugh, eat oranges, and lounge around on the bed; it’s the most naturalistic scene in the film. “You’re kind,” the bag lady says. “Why are you so kind?”

Waking up alone the next day, the heroine gets up in her silky bedclothes and reads in the paper about the scandal she caused in the café. After comparing her mirror reflection to her picture in the paper, she takes a drink and throws her glass at the mirror. Subsequently, she’s found drinking in a nearly empty theater (occupied only by five eerie women in black, seated in another section, who turn around to look at her in one motion), served wine by a stocky usherette; in her hotel room, watching the dwarf serving food on her black-and-white TV screen (before she removes a pair of scissors from the identical fowl on her dinner tray, and stabs a picture of herself dressed as a man); at a cabaret where an operatic soprano sings about drinking; in a café where Eddie Constantine and other “artists” sit; in a room where Bavarians eat sausages and sauerkraut and listen to a yodeler; and in. a lesbian bar, where one of the gray sisters notes, “The homosexual activity is an institution, a recreational activity.”

Framed by two odd sequences that audibly click as they cut from the heroine in long shot on a park bench to a close-up of one of her eyes, the heroine is seen drinking in contexts that are more fantastical and extravagant: playing Hamlet drunkenly on the stage (with audience members decrying her shocking lack of discipline); siting at office desk getting berated by her boss for drinking (while the gray trio through the door); walking on a tightrope outdoors with a parasol (the gray trio marveling that she can do.it drunk, without a net); on an outdoor spiral staircase at night, speaking in English and asking for a cigarette while a drummer starts a solo on a lower level which she eventually sings and chants along with, while both the dwarf and the grey trio watch on different levels;test-driving a car through a wall of fire on an empty field, with the trio again in attendance.

Later, she goes off on a ride on an aluminum-colored boat built to resemble a whale and called Moby Dick, where she’s again served wine. As the bag lady, rushing to catch up with her in the early dawn, drops some of her possessions on the street, a photographer gathers them up and takes snapshots of each one. Still later, a café manager named Willy (Cunter Meisner) goes off with the bag lady, a transvestite (Volker Spengler, a refugee from Fassbinder’s ln a Year of Thirteen Moons) gets tossed from a truck and comforted with wine by women, and the heroine passes out on some steep outdoor steps just before a crowd of people descend it (“As you make your bed, so you must lie in it,” says one of the honorable grey trio). In the final shot, though, the heroine’s back on her feet again, in another lush location, walking in high heels across a glass mirror floor, punching holes in the mirrors on either side of her as she goes.

Like Freak Orlando, Ticket of No Return is a movie about body language as well as what Ottinger refers to as an inversion of narcissism; in a sense these two preoccupations are constantly being explored together. In her interview with Mueller, Ottinger noted, “Narcissism has a double face: to love only oneself is self-destruction. I am using narcissism as a metaphor for self-destruction. What interests me in particular is that narcissism always involves a certain amount of anxiety, anxieties which art never talked about. In this film these anxieties are drowned in alcohol. I thought about how to represent this anxiety for a long time. It seemed evident to me that she hates herself.” For her literally divided stance towards notions of female identity, Ottinger thus situates herself at the same crossroads occupied in their separate ways by Chantal Akerman, Sara Driver, Yvonne Rainer, Jackie Raynal, and Leslie Thornton — a crossroads where questions of sexual roles and of reading one’s self in pursuit of identity ultimately dictate the nature and focus of many of the formal decisions.

***

The best summary of Freak Orlando I can offer comes from the detailed synopsis printed in the program to the 11th International Festival of New Cinema in Montreal (Fall 1982):

In the form of a “little theater of the world” (Kleines

Welttheater), a history of the world from its beginnings to our

day, including the errors, the incompetence, the thirst for

power, the fear, the madness, the cruelty and the

commonplace, in a story of five episodes.

First episode: where it is told how Orlando Zyklopa, with

her seven dwarf shoemakers, special attraction of the instant

shoe repair service at the Freak City department store, strikes

the anvil; how she is driven away by Herbert Zeus, director of

the store; then, as queen of the seven dwarf-athletes, how she

climbs up on the Trojan Horse; and finally how she refuses to

be the successor to a holy stylite, which leads to her death.

Second episode: where it is told how Orlando Orlanda,

alias Orlanda Zyklopa, is born as a miracle on the steps of a

basilicum in the Middle Ages and, with her two heads,

enchants those around her with a lovely song in two-part

harmony; how she can’t prevent the flagellants from taking

two acrobat prisoners and leading them out of the city in their

procession, which leads her to pursue them with the famous

Calli, a dwarf painter, up to the convent of Wilgeforte, the

bearded woman saint; how she is dressed in new clothes in

the department store warehouse; and how she goes through

an amazing transformation while Calli paints her portrait.

Third episode: where it is told how Orlando Capricho,

alias Orlando Orlanda, alias Orlanda Zyklopa, has to admit

that she has been taken by a special travel offer made by the

department store, announced by a seductive voice; how she

learns distrust when she sees her mirror image; how she falls

into the hands of the persecutors of the Spanish lnquisition at

the end of the18th century; how she has to undergo a

thousand dangers and adventures, barely escaping

internment in a prison; and how she is finally deported with

people of every description, which Calli El Primi illustrates

faithfully.

Fourth episode: where it is told how Mr. Orlando.. . in

front of the entrance to the psychiatric ward of a hospital, is

engaged by the freak-artists of a side-show travelling around

the country; how he quickly falls in love with one of a pair of

Siamese-twin sisters, named Lena, which the other, named

Leni, can’t stand; which is why Mr. Orlando, entangled in a

rather confused affair, stabs Leni with a dagger, which also

inevitably kills his Lena, whom he loved so much; and how

the head of the troupe is forced to deliver Mr. Orlando to

death, to comply with an old tradition of the artists.

Third episode: where it is told how Orlando Capricho,

alias Orlando Orlanda, alias Orlanda Zyklopa, has to admit

that she has been taken by a special travel offer made by the

department store, announced by a seductive voice; how she

learns distrust when she sees her mirror image; how she falls

into the hands of the persecutors of the Spanish lnquisition at

the end of the18th century; how she has to undergo a

thousand dangers and adventures, barely escaping

internment in a prison; and how she is finally deported with

people of every description, which Calli El Primi illustrates

faithfully.

Fourth episode: where it is told how Mr. Orlando.. . in

front of the entrance to the psychiatric ward of a hospital, is

engaged by the freak-artists of a side-show travelling around

the country; how he quickly falls in love with one of a pair of

Siamese-twin sisters, named Lena, which the other, named

Leni, can’t stand; which is why Mr. Orlando, entangled in a

rather confused affair, stabs Leni with a dagger, which also

inevitably kills his Lena, whom he loved so much; and how

the head of the troupe is forced to deliver Mr. Orlando to

death, to comply with an old tradition of the artists.

Fifth episode: where it is told how Mrs. Orlando, called

Freak Orlando because of her special preferences …. is

engaged as an entertainer and tours Europe with four

bunies; how she is in great demand as an attraction for shopping

center openings, family celebrations, etc.; how, finally, she is

engaged to do a show at the annual festival of ugliness; how

she crowns the winner and bestows a trophy with the

inscription, “Limping is the way of the Crippled,” and, at the

end of the festival, how we are told that the story is over.

At its funniest and best — a virtuoso solo performance by someone or other as Christ on the Cross that somehow manages to combine the best of both Lennie Bruce and Werner Schroeter in one very extended shot and set piece; domestic complications in the lives of Lena and Leni, the Siamese twins (enjoyably played by Delphine Seyrig and Jackie Raynal) — it is as rewarding as much of Ticket of No Return. On the whole, though, as the above summary may well suggest, the film is every bit as variable as a circus, and is best approached in just that spirit-as one would approach, say, a John Waters film.

Ottinger’s political focus in Freak Orlando is a lot closer to that of Todd Browning’s 1931 Freaks than it is to Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, from which Ottinger has taken only the notion of “an ideal protagonist. . .a figure who represents all the social possibilities-man and woman — which we normally do not have.” But the absorption in pure spectacle that one associates with late Fellini is still closer to the mark, making the matter of the film’s overall duration somewhat arbitrary, like an endlessly extendable chain of vaudeville turns. Currently in the works from Ottinger, one hears, is Dorian Gray im Spiegel der Boulevardpresse, which one suspects will take her whole involvement with narcissism and its inverse still further.