This appeared in the April 8, 1988 issue of the Chicago Reader and is reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. — J.R.

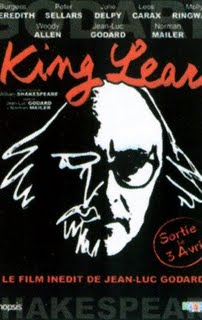

KING LEAR

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Peter Sellars, Burgess Meredith, Jean-Luc Godard, Molly Ringwald, Norman Mailer, Kate Miller, Leos Carax, and Woody Allen.

Jean-Luc Godard’s latest monkey wrench aimed at the Cinematic Apparatus — that multifaceted, impregnable institution that regulates the production, distribution, exhibition, promotion, consumption, and discussion of movies — goes a lot further than most of its predecessors in creatively obfuscating most of the issues it raises. Admittedly, Hail Mary caused quite a ruckus on its own, but mainly among people who never saw the film. King Lear, which I calculate to be Godard’s 34th feature to date, has the peculiar effect of making everyone connected with it in any shape or form — director, actors, producers, distributors, exhibitors, spectators, critics — look, and presumably feel, rather silly. For better and for worse, it puts us all on the spot; as Roland Barthes once wrote of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Saló, it prevents us from redeeming ourselves.

From its birth, a table-napkin contract signed by Godard and producer Menahem Golan of Cannon Films at the Cannes Film Festival in 1985, to its disastrous world premiere at Cannes two years later, the project has always seemed farfetched and unreal, even as a hypothesis. From its inception, the film might be regarded as the packaging principle gone haywire; while the original package never quite made it to the screen — script by Norman Mailer, who would also play Lear; Woody Allen as the Fool — enough vestiges of it remain to prove that Godard has essentially honored, or at least parodied, the dottiness of the initial concept. He even starts the film off with a real phone conversation between himself and Golan, with the producer urging him to finish the film in time for Cannes: “Where is this film? We have talked about it, promoted it; so where is it?” Now that one can actually see the movie in a theater, it remains partially hypothetical, alas, because commerce has effectively and summarily ruled out its most striking attribute. Having been fortunate enough to have seen King Lear at film festivals in Toronto and Rotterdam, I can testify that it has the most remarkable use of Dolby sound I have ever heard in a film. So far, however, to the best of my knowledge, the film has been shown in Dolby almost nowhere else, so you’ll have to take my word for it. The Music Box, which is showing the film locally in a limited one-week engagement, has stereo speakers, but while it’s probably the loveliest movie theater of the 20s still operating in Chicago and has a sound system that is quite adequate for most things, the multiple separations needed for Godard’s split, staggered, and overlapping channels — which play a variety of tricks with distance, space, depth, and layered aural textures — simply aren’t there.

So the popular Hollywood-fostered myth that the best film technology equals or guarantees the best art, pernicious enough to begin with, is given the brutal force of law by commerce. The conventional, simplistic uses of Dolby are the only kinds we can hear in theaters; ergo, they must be the best. Conversely, the dazzling contrapuntal sound work of Godard here (and, to a lesser extent, in the two-track Dolby of his Détective) can’t be heard; ergo, it can’t be the best. Consequently, the film’s disruption of the Cinematic Apparatus extends to the local rating system; if its sound track were fully audible, I would give it four stars rather than three.

After a flurry of alternate titles flashes on the screen (Fear and Loathing, A Study, An Approach, A Clearing, No Thing), we get two successive takes of a scene with Norman Mailer and his daughter Kate Miller playing themselves in a hotel suite, discussing the script he has just written for the film — a Mafia version of King Lear known as Don Learo — and momentarily interrupted by the first of many screeching offscreen seagulls. Then Godard begins to narrate offscreen in a raspy, grumpy voice how the “great writer” left the film with his daughter after a display of “star behavior.” (Mailer’s own account of the split, seconded by associate producer Tom Luddy, is that he would have gladly delivered Godard’s dialogue if it hadn’t been assigned to a character named Norman Mailer; apparently it touched on a theme of incest between himself and his daughter.)

With Mailer and Miller both out of the way, the film turns next to American stage director Peter Sellars, who introduces himself offscreen as William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth, and roughly describes his job as restoring what he can of his ancestor’s plays after a massive cultural memory loss was brought about by Chernobyl. Wandering around the town of Nyon, Switzerland (where all of the film is set), with some of the dreamy dopiness Godard would have assigned to Jean-Pierre Léaud in the 60s, he encounters a new Lear and Cordelia, played by Burgess Meredith and Molly Ringwald, in a fancy restaurant. As the film proceeds in fits and starts from there, we get snatches of Shakespeare’s Lear, snatches of what appears to be Mailer’s Don Learo, and snatches of what appears to be an earlier, unrealized Godard project, The Story, about Jewish gangsters Bugsy Siegel and Meyer Lansky in Las Vegas. (Three Journeys Into King Lear, as one printed title puts it. But does “King Lear” in this case refer to the play, the character, or the Cannon Films project?)

Like many of Godard’s films, King Lear has a situation and a group of characters rather than a plot, and a series of fresh beginnings rather than a development. “This was after Chernobyl,” intones William Shakespeare Jr. the Fifth. “We live in a time in which movies and art do not exist; they have to be reinvented.” Photographs of filmmakers — Cocteau, Bresson, Pasolini, Visconti, Lang, Tati, Welles — are introduced at various points, presumably as aides-mémoires. When Godard himself appears in the flesh, as Shakespeare Jr.’s guru, he is called Professor Pluggy, speaking semicoherently out of one side of his mouth, accurately described in the movie’s press book as a “Swiss Rasta Wizard with patch-cord dredlocks.” Portions of Shakespeare’s Lear fitfully recur (as when Lear receives telexes of fealty from Regan and Goneril, while the loving Cordelia pledges only “nothing,” or rather, as the film stubbornly and obsessively repeats it, “no thing”); Pluggy is visited in both a mixing room and a screening room; a copy of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is bandied about, the novel’s closing passage is quoted, and Edgar (French filmmaker Leos Carax) is assigned a wife named Virginia who “isn’t there”; great works of art (by Gustave Doré and Tex Avery, among others) are quoted, some of them lit by candles; a shoebox model of a screening room is illuminated by a sparkler; another printed title informs us that this is “a film shot in the back”; Woody Allen briefly appears as the Fool, aka “Mr. Alien,” in an editing room where a needle and thread are used to stitch pieces of film together.

“From a director of genius, a film which is, frankly, a mess,” wrote Richard Roud in Sight and Sound last summer. Certain other critics were so aghast that their reviews rivaled the film in perversity and incoherence; more than one, for instance, claimed that Godard had obviously never read the play — a curious claim considering how much of the play is used and chewed over. And even many of the more sympathetic critics seemed to suffer from various kinds of post-Chernobyl amnesia: the supposedly hip and knowledgeable Cahiers du Cinéma, apparently forgetting Burgess Meredith’s distinguished and varied past as an actor for Renoir, Lubitsch, and Preminger, as well as a writer and director, identified him simply as the trainer in Rocky and Rocky II; the Village Voice and its vigilant fact checkers, apparently forgetting Godard’s One Plus One, British Sounds, Letter to Jane, and his unfinished One A.M., identified King Lear as his first movie in English. One serious film critic seriously relayed to me her conviction that Godard’s method of editing King Lear was to throw the celluloid in the air and see where it landed.

The point of all these critical aberrations is that, like the perverse fate of the film’s sound track, the movie’s cantankerousness actually seems to encourage them. In other words, as an assault on the Cinematic Apparatus, it actively works to make the critical community, including Godard’s hardiest defenders, virtually tongue-tied. For a filmmaker whose gadfly relationship to dominant cinema has remained virtually constant for three decades, Godard is of course expected to be unexpected. But the relative narrative coherence of Sauve qui peut (la vie), First Name: Carmen, Détective, and Hail Mary may have lulled some viewers, Golan included, into expecting the kind of coherence (wrongly) associated with certain classic titles.

When I saw King Lear last year in Toronto, it struck me as being Godard’s most exciting film since Passion — his last feature, incidentally, where narrative incoherence reigned supreme — because of its prodigious and beautiful sound track. As important as words and sounds always are in Godard, this is possibly the only time that they truly overpower his images (considering Meredith’s magnificent line readings of Shakespeare as well as all the other elements in the shifting aural textures, a tonal range extending from seagull squawks and pig grunts to electronically slowed-down human speech and choral music); the shots are certainly attractive, but their relative lack of distinction for a Godard film actually seems functional in relation to the richness of the sound track.

Without Dolby, some of the film’s shortcomings become more apparent — such as its nervous habit of repeating and reshuffling shots and titles, a familiar Godardian reflex that by now suggests a tired jazzman falling back on an old lick in order to stall for time. But the strength that remains, which is principally destructive, is the film’s dialectical relationship to most of the other movies that we see, its capacity to make their most time-honored conventions seem tedious, shopworn, and unnecessary. This originality often seems to be driven by hatred and anger, emotions that are undervalued in more cowardly periods such as the present, just as they were probably overvalued 20 years ago. It is a source of energy that remains crucial to much of the avant-garde, epitomized by a line spoken by a character in William Gass’s story “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country”: “I want to rise so high that when I shit I won’t miss anybody.”

For Godard, it’s a legitimate source of pride that he won’t film anything to illustrate a scriptwriter’s point or provide continuity; his disdain for ordinary filmmaking practice becomes a creative challenge, and, in terms of his limited capacities for story telling, a calculated risk. The previous Godard film that King Lear most resembles — the insufferable Wind From the East (1970), prized by many academic armchair radicals for its simplistic and “teachable” theoretical schemata — also confronts narrative from a nonnarrative position, but with some important differences. Even at his most absurdist, as in Lear, Godard has a lot more knowledge at his disposal 16 years later — in knowing how to film nature, appreciate or ponder an actor or a text, light a shot, or simply fill a moment with sound, color, shape, and movement. What he seems to have less of — in the absence of his former cinephilia and Marxism — is a pretext for getting from one of these moments to the next.

If Picasso’s various periods as an artist are often identified by separate colors, Godard’s periods might be linked to different styles of self-portraiture. From the beginning of Breathless (1959) to the “end of cinema” title concluding Weekend (1967), it was Godard the film critic and the all-purpose sage. Godard #2, who lasted roughly from May 1968 through the mid-70s, was a political/theoretical rebuke to his predecessor, working principally in 16-millimeter and in collaboration with others (first with Jean-Pierre Gorin and the Dziga Vertov Group, then with Anne-Marie Miéville at their short-lived studio, Sonimage, in Grenoble). Godard #3, who began around the time that Godard moved with Miéville back to his native Switzerland, also marked a return to more commercial considerations (i.e., stars and stories — which Godard #2 had mainly abandoned) and a more concerted move toward placing himself in his work — either literally, as an actor, or autobiographically, as in Sauve qui peut (la vie) or Passion, where actors stand in for him.

Properly speaking, as an actor, Godard #3 has A and B versions: the abrasive, crotchety, boorish Godard who figures in First Name: Carmen, Meetin’ WA (his taped 1985 interview with Woody Allen), and King Lear; and the more benign, elder statesman persona who appears in Soigne ta droite (his most recent feature) and some of his more recent interviews and TV appearances. The fact that 3A and 3B are consecutive suggests that Godard may be beginning to mellow, but the difference may also have something to do with money and power. Just as the theme of prostitution has cropped up frequently in his work, but only when he shoots in 35-millimeter, Godard the curmudgeon seems likelier to emerge when he has to share space with bankable stars.

On the other hand, there’s a minor tradition detectable in some of Cannon Films’ more artistic productions that King Lear certainly belongs to — what might be called the uncompromised/personal home-movie tradition. John Cassavetes’s Love Streams and Norman Mailer’s Tough Guys Don’t Dance are the two most distinguished examples that come to mind, both using their writer-director’s homes as their central locations, and both so supremely personal on the level of style that every passing inflection — from incidental uses of music to line deliveries to camera angles to editing rhythms — expresses the personality of the creator. (One wonders if Raul Ruiz’s forthcoming Treasure Island for Cannon will have some of this quality.)

King Lear isn’t literally set in Godard’s home, but according to my atlas, it’s no more than a few miles away. More importantly, it registers as a personal work in a way that most of his recent features do not. One isolated thematic example of this can be gleaned from a recent interview — that the shoebox model of a screening room duplicates a toy cinema that Anne-Marie Miéville built for herself when she was eight years old. The point of this detail isn’t to argue that we all need a skeleton key to the film, which Godard’s or Miéville’s personal life supplies, but to suggest that many of its meanings are too hermetic by design to fall within our grasp.

In fact, one might argue that the film’s deliberate elusiveness can be traced back to a particular reading of Shakespeare’s Lear — specifically, the refusal of Cordelia to declare her love for her father, a king relinquishing his power, which sets the whole tragedy in motion. Unlike Goneril and Regan, her sisters, who comply with the old man’s demand that they convert whatever love they might claim to have for him into a commodity, a public display of “proof,” Cordelia — who later proves to be his only faithful and loving daughter — can only declare, “Nothing,” which leads him to disinherit her. This “nothing,” which Godard’s film pointedly represents as “no thing,” points to the refusal to become a commodity, to function as an object — a refusal which, as I have tried to show, is basic to the film’s strategies, and relates to more than just a refusal to behave like a normal, “consumable” product. Theoretically and practically, a film that is “no thing” threatens and challenges the functioning of the Cinematic Apparatus itself. Indeed, as Golan himself expresses the dilemma, “Where is this film?” Like Lear, we all wind up disinheriting it, much preferring the comfortable lies of a Goneril or a Regan.

Consider, for instance, the movie’s stars, its principal bankable assets: Molly Ringwald and Woody Allen for starters, Mailer, Sellars, Meredith, and Godard himself after that. In order to use the first two of these, and possibly some of the others, Godard had to agree not to use their names in the advertising. Moreover, he uses most of them in a way that contradicts their status as stars: Sellars is assigned the Woody Allen schlemiel part while Woody gets a few lines of Shakespeare but no laughs at all; Ringwald is framed and lit in a manner that makes her virtually interchangeable with Isabelle Huppert in Passion; Godard makes his own barks and mumbles border on incoherence. Only the nearly forgotten Burgess Meredith is permitted some of his former eloquence.

In a related fashion, whatever might turn the film into “a Shakespeare play,” “a Mailer script,” “a story,” or even “a Godard film” in the usual sense is purposefully subverted. The film aspires, like Cordelia, to be (and to say) “no thing,” to exist and to function as a nonobject: ungraspable, intractable, unconsumable. For a movie that is concerned, like Shakespeare’s play, with ultimate essences rather than fleeting satisfactions, it is an aspiration that has an unimpeachable logic.