From the April 3, 1998 Chicago Reader. My affection for Richard Linklater’s most underrated film has only grown over time. — J.R.

The Newton Boys

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Richard Linklater

Written by Linklater, Claude Stanush, and Clark Lee Walker

With Matthew McConaughey, Skeet Ulrich, Ethan Hawke, Dwight Yoakam, Julianna Margulies, Vincent D’Onofrio, and Chloe Webb.

Shortly before reseeing Richard Linklater’s sixth feature, The Newton Boys, I caught up with his first — a Super-8 opus from 1988 with the enigmatic title It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books [see below]. Essentially an epic of inaction starring Linklater himself, the movie consists mainly of hanging out, taking train rides, driving, using a variety of vending machines, doing household chores, and watching movies on TV. The film might be described as a noncommercial version of his second feature, the 1991 Slacker — a Slacker without much dialogue or plot, devoted to the everyday pleasures of vegetating and drifting. Some of it reminds me of structural films and of the work of Jon Jost. Just about all of it is attractively shot. And Linklater’s film references — including choice bits from the sound tracks of The Killing and Some Came Running and an extended ravishing clip from Gertrud — pop up like generous, unexpected gifts.

Come to think of it, generous, unexpected gifts is what Linklater’s movies are all about. I still haven’t made it back to Dazed and Confused (1993), but rereading my own churlish capsule — I called it “a good example of how throwing money at gifted low-budget independents can remove the originality from their work” — I’m stung by my own lack of generosity and common sense. Having seen Linklater’s latest film, I now know that this judgment has to be wrong, because considerably more money was thrown at The Newton Boys, and not a cent of it was wasted, nor was any serious part of what makes Linklater an original sacrificed.

I suspect that my main problem with Dazed and Confused was generational distance. Yet if The Newton Boys, like Before Sunrise (1995), proves anything, it’s that Linklater knows more about our film heritage than James Cameron, Walt Disney, and Steven Spielberg combined — and more about our past and present as Americans. Consequently, believing in the future of American movies means believing in Richard Linklater much more than in these other guys — even though, unlike them, he doesn’t work for the company store and doesn’t qualify as much of a storyteller.

Working for the company store generally entails giving multinational executives exactly what they’re looking for: thrills, chills, spectacle, global saturation, tons of braggadocio and hype — the same elements found in this year’s terminally tacky Oscar telecast. What’s known in the trade as streamlined storytelling is what drives this approach. (The telecast producers’ idea of good storytelling: cutting to Spike Lee in the audience after any black person appears onstage for any reason.) But having now seen the only two of Linklater’s six features that don’t squeeze all the action into one clearly defined 24-hour period, I can see why he used that structure in Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, and SubUrbia (1995): because storytelling, at least as the company store understands it, isn’t really his forte. So why not let the natural shape and flow of a consecutive day and night form four of his narratives, if narrative is only a secondary consideration?

This film is based on an oral history — The Newton Boys: Portrait of an Outlaw Gang by Willis and Joe Newton, as told to Claude Stanush and David Middleton — and it’s a fascinating true-life tale, but not the kind designed to turn you into the slave of pile-driving yarn spinning. In 1918, after Willis Newton gets out of prison for a crime he didn’t commit and goes through a frustrating stint of cotton picking, he comes home to Uvalde, Texas, and enlists two of his brothers and a nitroglycerin expert in a scheme for robbing banks. They go in the middle of the night in part because they don’t want to kill or hurt anyone, and Willis figures that the bankers they’re stealing from, all covered by insurance, are thieves themselves. As Willis put it to Stanush years later, “We was just businessmen like doctors and lawyers and storekeepers. Robbin’ banks and trains was our business.” They got caught six years and 80-odd robberies later — during which time another Newton brother joined them — after pulling off their biggest job, a $3 million mail-train heist a few miles outside of Chicago. What happened after this point is in some ways even more significant and surprising than their crimes. Some true-crime buffs will know the outcome already, but everybody should stick around for the final credits.

There isn’t a dull moment in The Newton Boys — its true story is packed with charm and interest — but the user-friendly storytelling that the company store banks on isn’t as important as the film’s other virtues: direction of actors, period detail, sense of rhythm, sweet-tempered tone, comic flavor, visual taste, and imagination. Both times I saw the picture I periodically had trouble telling three of the four Newton boys apart. The exception is Willis, the brother played by Matthew McConaughey — in what is surely his best and most likable performance — because it’s always clear that he’s the hero and the one in charge. (The fact that McConaughey hails from Uvalde himself likely added to his investment in the part.) But it’s surely no fault of the actors that brothers Joe (Skeet Ulrich), Jess (Ethan Hawke), and Dock (Vincent D’Onofrio) lack the instant legibility of even Disney’s seven dwarves. The problem is that Linklater has so much to say and do in scenes involving two or more of them that their identities tend to slide in and out of focus. Similarly, certain plot strands — such as whether the father of the ten-year-old son of Willis’s girlfriend Louise (Julianna Margulies) is dead or alive — are taken up only to be abandoned; probably they got lost in the shuffle of the final editing. (It also has to be said that the scenes with Louise after her first meeting with Willis are conventional to a fault, even shopworn.)

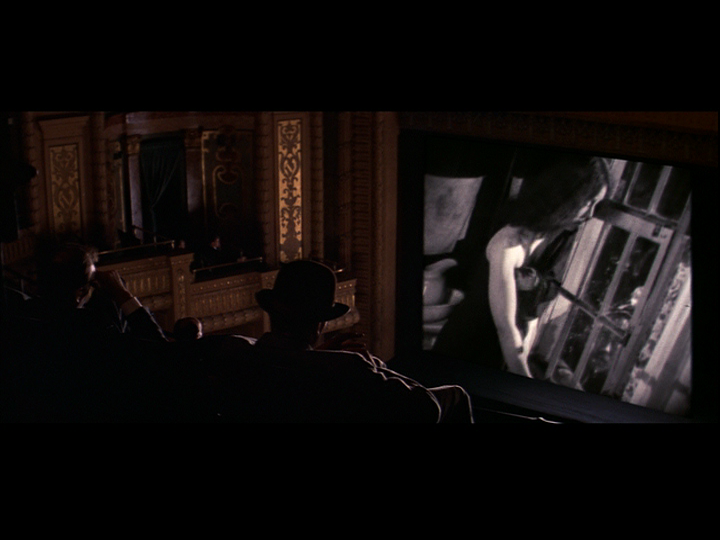

I can’t tell you which two gang members are watching Erich von Stroheim’s Greed from the balcony of a picture palace after a semibotched daytime heist in Toronto in 1924 — my favorite movie reference in any Linklater feature. I’m much too preoccupied with the Greed scene itself, with Trina (ZaSu Pitts) refusing to let Mac (Gibson Gowland) in from the cold when he knocks at her window, with the weird and fabulous way the huge movie screen is slanted in relation to the balcony and the plush theater accoutrements, and with the comment of one of the two gang members: “Hey, I know that gal — I went to Sunday school with her in Parsons.” Pitts was born in Parsons, Kansas, in 1898, so I suppose one can deduce that the person uttering this line isn’t a Texan at all, hence not a Newton but the nitroglycerin expert, Brentwood Glasscock (Dwight Yoakam).

But figuring out who the two characters are has so little to do with this wonderful little stretch of film that it matters as little as the fact that Greed was actually released several months after the scene is supposed to take place. Cameron or Spielberg wouldn’t be caught dead creating a mysterious parenthesis of this kind, a discreet pocket of bliss in which audience members are invited to lose themselves: the company-store necessity of lurching the story and the audience forward eliminates the very possibility of such a dreamlike interlude. Even if they had the imagination to think up this daffy scene and made sure you knew exactly who the two characters were, the poetry that comes as easily to Linklater as breathing would still have eluded them.

Some of the film’s most striking moments, in fact, are based on film history: the opening old-fashioned black-and-white credits, complete with a “Passed by the National Board of Review” title and an introduction to all the cast and characters punctuated by wipes; a beautifully timed iris opening out on the first ‘Scope shot after the credits; a breathtaking montage chronicling the gang’s exploits circa 1922, including a gorgeous glimpse of the group posing for a photograph beside a creek and a brief bout of bicycling that clearly evokes Jules and Jim — whose playful, affectionate, gliding style is one of Linklater’s reference points throughout. More generally, the film gracefully conflates the look of westerns and gangster films. As the founder and artistic director of the Austin Film Society, Linklater knows at least as much about the emotional content of film history as he does about its forms; the evidence of his understanding was already fully apparent in Before Sunrise — a movie that had as much to say about Hollywood love stories like The Clock as it did about the difficulty of modern relationships and how to spend a day in Vienna.

Even more striking is Linklater’s way of dressing sets (with the help of production designer Catherine Hardwicke) and actors (with costume designer Shelley Komarov). The movie expresses and generates a sustained curiosity about and fascination with the way streets, clothes, hotel lobbies and bedrooms, banks, storefronts, speakeasies, cars, trains, houses, oil wells, and bathtubs looked in the late teens and early 20s. Such details as an early passing street scene of three little girls performing for the Baptist Orphans Relief Fund, an array of magazines at a cigar stand, and a weathered and tattered Wild West show the gang briefly visits illustrate the sort of intricate filigree at which the movie excels. These moments also invariably stop the storytelling dead in its tracks, inviting viewers to climb inside the space and roam around. From this standpoint, it might be argued that the more radically contemplative It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books represents Linklater’s art at its purest. But because the real story of The Newton Boys is the kind of ambience, personality, and feelings that blossom out of a milieu and the taste of these qualities when you roll them around on your tongue, the relative absence of Disney-Spielberg-Cameron mechanics is more a gain than a loss.

Whether the movie happens to be Song of the South, Empire of the Sun, Schindler’s List, or Titanic, the streamlined route into history is to start with the cliched “archetypes” of a place and time and never stray too far from them for fear of challenging the audience. If you give viewers what they think they already know and continue to flatter them for their knowledge, they can be shuttled through the specifics of the plot as easily as through the key points in a theme park ride. The way this simplifying process entails mental shrinkage — whatever the size of the sets — is literalized in the design of Disneyland’s Main Street, U.S.A., where every brick, shingle, and gas lamp is five-eighths normal size. (As Uncle Walt put it, this approach makes “the street a toy….Besides, people like to think their world is somehow more grown-up than Papa’s was.”) The same principle is expressed in cartoons when aerial locations are conflated with maps, as in the opening shot of Florida in Dumbo or in the various evocations of South America in Saludos Amigos. Incidentally, it also explains Cameron’s idiotic notion of having Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon go down with the ship: if you want to demonstrate the heroine’s art savvy in 1912 without making the audience feel any less sophisticated, you’ve got to shove that familiar totem into her stateroom. [2010 footnote: according to the Internet Movie Database, “The painting by Picasso (sic) is not the famed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, but merely a painting in the same style.”]

Moreover, if shuttling viewers through thrilling, chilling plot turns is your goal, then violence, death, or both — the prime emblems of closure — are most likely the little “gifts” dispensed near the end of the line: Bobby Driscoll is gored by a bull at the climax of Song of the South, while Spielberg gives us the A-bomb and the gas ovens and Cameron achieves artistic apotheosis with hundreds of floating corpses.

By choosing to tell a bank-robber story in which no one gets killed and most of the violence is light enough to pass for slapstick, Linklater shows he isn’t interested in this sort of game plan. Even though the jolly period music by Jelly Roll Morton and others makes you periodically anticipate the retributory bloodbaths of Bonnie and Clyde and its multiple spin-offs, the movie keeps depositing you instead in privileged pockets of historical space, setting you loose in a re-created world and asking you to find your own way. In this respect, the nearest cousin to the spatial adventure of The Newton Boys can’t be found in American cinema — which is completely tied up in remasticating what it already knows — but in Chinese cinema, where a sense of its own history is just beginning to take shape. I’m thinking specifically of Stanley Kwan’s ravishing Actress (also known as Center Stage and Ruan Ling Yu), an early-80s look at Chinese filmmaking in the early 30s that proposes the past as something larger and more labyrinthine than the stereotypical present, more worthy of our exploration and wonder.

Couldn’t one interpret the nostalgia in The Newton Boys as a form of political defeatism, a strategic retreat to a “simpler” past? Only if one doesn’t pay attention to the film. There’s a distinct political message lurking behind Linklater’s method and story, a humanist message that combines a bit of Capracorn with a dash of populist anarchism — the notion that we’re all thieves by necessity when we’re dealing with the company store, which robs us blind and then asks us for more money in return. In this respect Willis’s failure as an oilman is as significant as his success as a bank robber: he discovers that even when he tries to play the capitalist game of drilling for his wealth instead of stealing it, Standard Oil and Gulf Oil suck his resources dry. Linklater’s awestruck absorption in the American past simply proposes a better and clearer way of looking at the present.