From Film Comment (January-February 1975). (January 23, 2012 update: Thanks, once again, to the ever-vigilant Ehsan Khoshbakht for spotting a few typos here and thus enabling me to correct them.)– J.R.

October 8: Victor Erice’s EL ESPIRITU DE LA COLMENA (THE SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE). I’ve been trying all weekend to come up with an adequate description of this lovely Spanish film, but I can’t get anywhere. A colleague recently spoke of the film as “beguiling,” which seems like an honest start. Two remarkably expressive little girls, Ana Torrent and Isabel Telleria, see James Whale’s FRANKENSTEIN at a traveling film show that stops in their village in Castille. Afterwards, Isabel explains to her sister that the monster is still alive — and indeed, he makes a brief appearance in the final reel. The girls’ father is a bee-keeper who broods over Maeterlinck, while the mother writes unexplained letters to someone in France. Isabel plays dead for a bit, and Ana believes her. Ana befriends a fugitive soldier who is eventually killed.

I don’t know what sense to make of either the plot or Erice’s beautiful honey-tone colors and honeycomb compositions, but I find the film haunting and rather spellbinding in a muted way, and emotionally it all seems to add up to something. Like Mervyn Peake’s unnerving fantasy-novella Boy in Darkness, its overall effect is unmistakable yet strangely unaccountable, at least by me. All I can do is point and hope you’ll get a chance to encounter it.

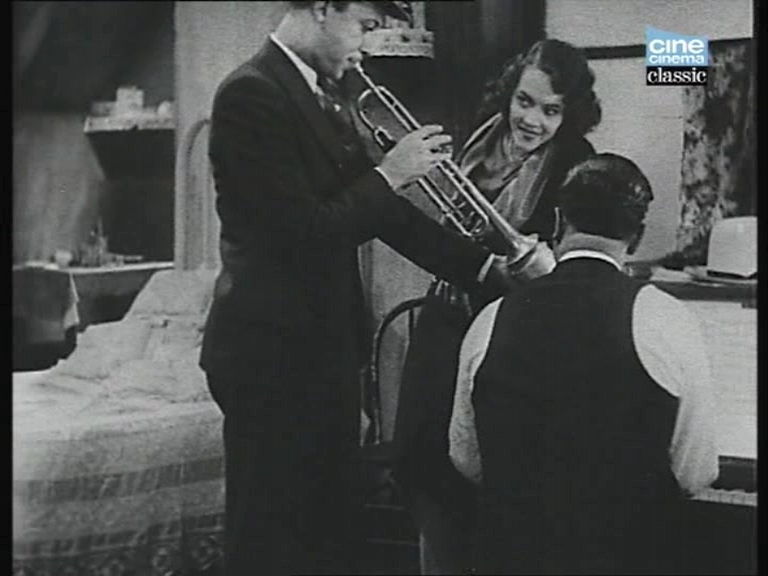

October 10: A program of films and extracts featuring Duke Ellington at the National Film Theatre, judiciously selected, arranged, and presented by David Meeker and Charles Fox. The earliest treat -– and the first recording of Ellington on film -– is BLACK AND TAN (1929), directed by Dudley Murphy the same year as his Bessie Smith film, ST. LOUIS BLUES, with an equally creaky plot and a lot more arty chiaroscuro. But it is full of indelible details and moments. Duke’s elegant rehearsal of the title tune with a trumpeter, interrupted by the arrival of two piano removers (“Move your anatomy from that mahogany!”); a nightmarish dance routine of five men of decreasing heights in tuxedos on a polished, mirror-like floor, combining cancerous Busby Berkeley-like images of multiplicity with a period species of voodoo jive; a death scene worthy of Little Nell’s, with all the sidemen crowded around Fredi Washington’s bed playing a somber blackout melody (the title tune again) and projecting tasteful death shadows on the wall, capped by a final image of Duke fading and blurring out like a candle flame as the dancer-heroine loses consciousness.

The last excerpt in the program, from DUKE ELLINGTON AT THE WHITE HOUSE (1969), offers the satisfying spectacle of Ellington sharing a stage with Nixon without losing an ounce of cool or integrity in the process, outclassing his sponsor with every gesture of courtesy and wit and leaving no doubts at all about who is the presiding nobility. It’s a significant contrast to Nixon’s nauseating John Ford tribute, which contrived to remove the Brechtian distance from the old dodger’s vision and leave us with a chauvinistic postage-stamp of mythology for right-wing auteurists to slobber over — the perfect companion-piece to Ronald Reagan’s program introduction to Bogdanovich’s DIRECTED BY JOHN FORD at the New York Film Festival in 1971.

Other parts of the Ellington anthology raise the whole complex issue of compatibility between jazz and film as independent and/or interactive art forums: clearly the best jazz doesn’t always add up to the best cinema , and the contrast of filmic approaches to the music is interesting for its illustration of diverse ways of dealing with the problem. A lunatic extract from MURDER AT THE VANITIES (Mitchell Lesien, 1934) frantically interlaces plot and performance, ending with the entire Ellington band murdered by a spray of machine-gun bullets; the quasi-abstract title credits of CHANGE OF MIND (Robert Stevens, 1969) gives the music a more neutral surface to play against, but wind up serving as a relatively static backdrop. Perhaps the only moment in the entire evening when jazz becomes cinema occurs in Will Cowan’s wonderful SALUTE TO DUKE ELLINGTON, a Universal short of 1950: in the midst of a tune, Ray Nance steps forward and “improvises” Louis Armstrong in everything but his music — aural improvisation suddenly blossoming into visual improvisation as he mugs and mimes his way through an inventory of recognizable Satchmo stances, in a spirit perfectly matching that of the music around him.

October 13: The same issue of musical and filmic values affecting one another crops up in a revival of GUYS AND DOLLS on BBC television. Nearly all of the critical accounts of this underrated movie suggest that it’s weakened by the “unprofessional” singing of Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons; for my money, Frank Loesser’s music has never come across better. Why? Because the vulnerability of Brando and Simmons performing these tunes enhances their characters, making them unusually tactile as musical-comedy figures.

The slight quavers and hesitations in their voices as they approach and probe at certain notes give their songs –- “I’ll Know,” “A Woman in Love,” “If I Were a Bell,” “Luck Be a Lady” –- an additional emotional layer precisely because of the risks and tensions involved, which immediately translate themselves into the emotional risks taken by Sky Masterson and Sister Sarah Brown. (Is GUYS AND DOLLS the only Method musical?) Listen to Robert Alda and Isabel Begley in the original-cast album of the stage production, and you’ll hear to what extent “professionalism” can bleach out or eliminate these touching overtones, giving us a more polished surface with much less sense of the human beings/actors behind the voices. Which only demonstrates that an aesthetic for the film musical, musically speaking, shouldn’t necessarily be the same aesthetic used for stage musicals.

One wonders how Straub will resolve the related problem of camera placement in his MOSES AND AARON film: will he reveal the necessary facial distortions of the singers in closeups, or preserve the opera house illusion of relative repose in long shots?

October 15: At long last, a Fassbinder film I can celebrate! MARTHA, inaugurating a season of new German cinema at the National Film Theatre, pushes the campy and distancing effects of THE BITTER TEARS OF PETRA VON KANT and ALI until they serve up their richest fusions and clearest contradictions. Practically any given moment of this startling masterpiece is enough to warrant a scream or a giggle, and staggering uneasily between these screams encourages us to appreciate the horror story (virgin librarian loses father, marries sadist) in all its various and overlapping aspects. A parody of bourgeois marriage, informed by Fassbinder’s characteristic empathy and compassion; an improbable meeting ground for Hollywood in the Fifties and Dreyer (with some scenes suggesting either a Minnelli remake of GERTRUD or a Sirk adaptation of Georges Bataille, with intermittent traces of VAMPYR); a festival of fluid camera movements, balancing deep-focus effects and candy-box colors; and a mounting sense of the monstrous as Helmut’s insane demands and accelerating cruelties against his fragile wife fit with increasing snugness into the commonplace banalities of soap opera.

Helmut is played by Karlheitz Böhm, the creepy title hero of PEEPING TOM — fleshed out here to suggest a hulking slab of respectable granite -– while Martha is expertly incarnated by spindly and sparrow-like Margit Carstensen, in a freakish mannerist performance of near-epic proportions. People who don’t like this film call it self-indulgent, which I take to mean not boring enough to qualify as classicism nor quite rigorous enough to qualify as either measured or monolithic. I suppose five minutes or so could be dropped from the film without serious damage; but considering the fact that the film virtually lives in its excesses, I can’t imagine preferring a tamer or saner version.

November 1: Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s PENTHESILEA: QUEEN OF THE AMAZONS is clearly and unabashedly a theoretical film, which means that only a handful of people in London seem interested in seeing it. No matter. Split into five autonomous “one-take” sequences -– actually two reels each, with semi-invisible ROPE-like junctures -– this ambitious and difficult work explores a series of didactic possibilities, how to convey information through sounds and images, and invites us to compare and juxtapose the alternatives at every level.

Starting with a mime of Kleist’s Penthesilea filmed in one static and alienating long shot, the film subsequently reverses itself in a sequence featuring words and camera movements, where a lecture about the film’s subject by Wollen while moving through a garden terrace and living room is accompanied by the“subtext” of the camera’s independent path through the same general space, zeroing in on the cue cards left behind by Wollen for some witty, playful, and paradoxical effects. Next comes a lengthy presentation of diverse objects relating to the Amazon myth (from ancient sculpture to Wonder Woman frames) accompanied by Berio’s “Visage” and separated by animated wipes and maskings; then a simultaneous recitation of a feminist text and projection of a silent feminist film; and finally sequence number five which presents four TV monitors replaying the four previous sections (eventually supplanted by new material) while the camera periodically isolates individual scenes and soundtracks.

Initially somewhat soporific –- before the overall design becomes evident –- but ultimately fascinating, PENTHESILEA offers just as much as one is willing to bring to it, rewarding intellectual collaboration but scrupulously avoiding the discourse of illusionist narrative while exploring “the space between a story that is never told and a history that has never yet been made” -– contrasting diverse presentations of texts and relative surfaces that accumulate around a hypothetical subject.

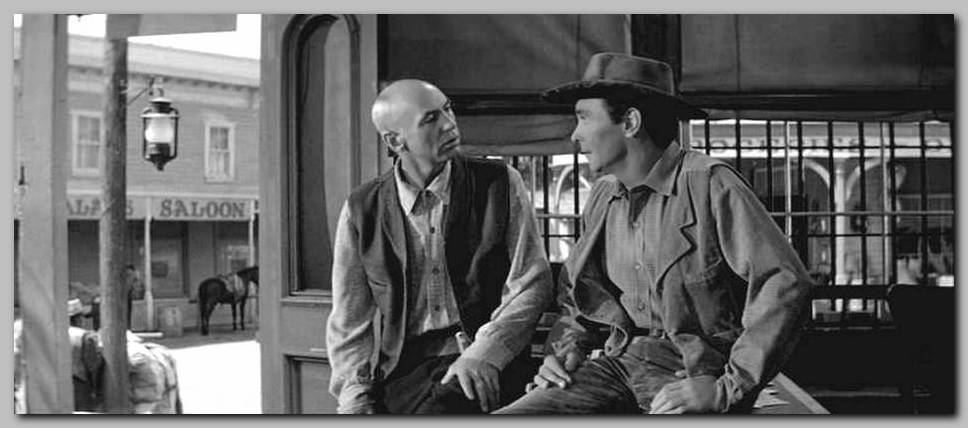

November 16: Samuel Fuller’s FORTY GUNS on BBC-2. Concluding a series of three Fuller Westerns –I SHOT JESSE JAMES and THE BARON OF ARIZONA were shown the previous weeks -– this rough gem is brutally distorted by the BBC’s infuriating habit of (1) cutting off both sides of the CinemaScope frame and (2) re-editing the film in the process, so that now (for instance) the celebrated endless tracking shot through the town is marred by a cut. This sort of tampering is nothing new, of course: only three weeks ago, BBC-2 had the lousy idea of broadcasting Dovzhenko’s EARTH with added sound effects – a barrage of twittering birds and crickets, moaning peasants, etc. – which sabotaged the film even if one turned the volume off, because it necessitated showing it at the wrong speed.

Since FORTY GUNS has a partially incomprehensible plot to begin with, the losses tend to be strictly formal rather than narrative (apart from the inevitable censor’s cuts). But what still comes through with remarkable clarity is how –- in striking contrast to the mystery-play concentration and unswerving narrative progression in I SHOT JESSE JAMES -– FORTY GUNS is such a workshop of uncontinuous formal ideas. Virtually every character, scene, and shot stands at an oblique angle to every other, splintering an already not-so-lucid storyline into a thicket of uneven, autonomous slabs jutting out in every conceivable direction. This cacophony of styles, like that of Godard in the late Sixties, is curiously enough an attempted negation of style. So powerful is the force of the dialectic in each director’s work that their strategies often seem to derive from the premise that no single approach is possible, therefore every possible approach is necessary.No wonder that the ideology of both directors’ films is so ambiguous: CHINA GATE is as full of paradoxes as LA CHINOISE.

Refusing to stand still long enough to sustain a consistent strategy, FORTY GUNS seems to benefit rather than suffer from its abbreviated shooting schedule -– a ten days wonder with all forty of its guns (figuratively) firing at separate targets, resulting in one of the most non-linear movies in the history of Hollywood. Perhaps it is the one Fuller film that most reflects his legendary shooting method of beginning every shot by firing a gun and ending it with the command “Forget it”: it is hard to think of a more succinct parody of existentialism.