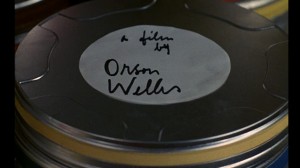

Commissioned and published for the Voyager laserdisc of F for Fake in 1995. My thanks to Marcio Sattin in São Paulo for giving me a printout of this untitled “lost” essay in Spring 2015, which I’ve slightly re-edited.-– J.R.

Orson Welles’ two major documentary forays stand roughly at opposite ends of his film career: It’s All True (1942) and F for Fake (1973), and together the two projects’ very titles express a dialectical relationship to the documentary. Both belong to a form of documentary known as the essay film that interested Welles throughout his career. Notwithstanding some Wellesian hyperbole, it seems safe to say that both titles accurately convey the overall essence of their respectiive projects: Most of the never-completed It’s All True, as Welles conceived and shot it, was true; most of F for Fake is fake -– a fake documentary about fakery, with particular attention devoted to art forger Elmyr de Hory, to author Clifford Irving, and to Welles himself. As Welles put it in a 1983 interview, “In F for Fake I said I was a charlatan and didn’t mean it . . . because I didn’t want to sound superior to Elmyr, so I emphasized that I was a magician and called it a charlatan, which isn’t the same thing. And so I was faking even then. Everything was a lie. There wasn’t anything that wasn’t.”

F for Fake remains one of Welles’ most controversial works. For many spectators, it’s not really a “Welles film” at all. By refusing to include “typical Wellesian” shots –- a deliberate ploy, one learns from a 1982 interview – some viewers may feel they’ve been sold a bill of good. For many people, the Welles legend has much more potency than the reality; F for Fake seems to be both inspired by this paradox and structured around it.

One of the first “tricks” in F for Fake occurs during the opening credits a few minutes into the film, when the word “practioners” appears on the screen. No such word exists in the English language, yet because of the speed with which we read it -– the film frame is quicker than the eye – most of us assume that the word is probably “practitioners”. Appearing only four shots after a passing allusion to Welles’ War of the Worlds radio hoax, the first of his major pseudo-documentaries, this glancing piece of legerdemain is one of the earliest signs that our own gullibility — a form of imagination – is the film’s principal subject (the audience’s imagination remains the essential tool in Welles’ bag of tricks throughout his career). What we think is what we get, and what we think is not so much what we see as what we think we see. Welles spent almost a year editing this film in Paris, working secen days a week in three adjacent editing rooms. Even repeated viewings won’t exhaust its bountiful arsenal of editing pranks, some much less obvious than others.

Like many things in Welles’ career, the film began more as a spontaneous improvisation than as a carefully worked-out project. In the early 70s, Welles was interviewed by French filmmaker François Reichenbach for a documentary about art fakery through the ages; also interviewed was Clifford Irving, known at that time as the author of Fake. After Irving’s own fraud involving the Howard Hughes autobiography was uncovered, Welles became fascinated by the paradox of Irving being interviewed about fakery while he was hatching a major hoax himself. This wasn’t long after Pauline Kael’s notorious essay “Raising Kane” first appeared, arguing — erroneously, as it later turned out – that the sole author of the Citizen Kane script was Herman J. Mankiewicz. The protracted debate about authorship clearly related to de Hory, Irving, and certain issues of Welles’ own career.

Purchasing Reichenbach’s outtakes, Welles set out to create an essay film that dealt with all of these questions, and it’s small wonder that the resulting work raises questions of its own. F for Fake is every bit as much a “Welles film” as Citizen Kane; it’s also equally, in terms of script and title, a coauthored one: Just as the title of Kane came from the film’s producer, George Schaefer, and much of its script was by Mankiewicz, the final title of F for Fake was supplied by its lead actress, Oja Kodar –- Welles’ companion and major artistic collaborator for the last quarter-century of his life –- who also wrote a story that supplied the basis for the film’s “Picasso episode”.

Indeed, the first time that I saw F for Fake -– at a private screening in Paris in 1973 – the cryptic press materials at the time identified the film as ?, listed Welles and Reichenbach as co-directors, and assigned the script to Olga Palinkas (Kodar’s given name). The previous year, when I had been fortunate enough to have interviewed Welles while he was still editing the film, he told me that the title was Hoax and that the film was “not a documentary” but “a new kind of film”. The irrelevance of labels and assigned credits to most works of art is, after all, largely what F for Fake is about. -– Jonathan Rosenbaum