From Film Comment (January-February 1982); reprinted in my book Film: The Front Line 1983. My thanks to Jon Jost himself for furnishing me with the frame grabs from Last Chants for a Slow Dance and Stagefright. — J.R.

1. “This is a movie, a way to speak. It is bound, like all systems of communication, with conventions. Some of these are arbitrarily imposed, some are imposed by economic or political pressures, some are imposed by the medium itself. Some of these conventions are necessary: They are the commonality through which we are able to speak with one another in this way. But some of these conventions are unnecessary, and not only that, they are damaging to us, they are self-destructive. Yet we are in a bad place to see this. We are in a theater.” Jon Jost, addressing the camera and spectator in Speaking Directly (1974).

2. Despite five substantial and in many ways remarkable features under his belt since 1974, and nineteen shorts since 1963, Jon Jost at 38 is still a long way from becoming even an arcane household name in this country. Not that he makes it easy on anyone. His originality, technical virtuosity, and political sophistication have all tended to work against him by showing the rest of us up — thereby banishing him from most of the restricted genre and market classifications designed to protect us from his scorn, under avant-garde and mainstream umbrellas alike. In a manner that seems exasperatingly and inescapably American, that alternately warms and chills my blood, Jon Jost embodies the dangers, limitations, and intransigent strengths of isolation more graphically than any other contemporary independent I know — with an authenticity whose challenges often leave a disturbing aftertaste.

An anarchist outsider by self-definition, whose impossibly slim budgets — $2,500 for Speaking Directly, his first feature, in 1972-73; $3,000 for Last Chants for a Slow Dance, his third, in 1977 — are offered like tart reproaches to other filmmakers; Jost has tended to amass a reputation more than a following in the U.S. (In England and, more recently, Germany, he appears to have somewhat more clout. )

His most recent and (by far) most experimental feature Stagefright was shot for German TV in a somewhat Dr. Mabuse/Strangelove spirit (“I wanted to lock actors in a black room for four days and see what would happen… and orchestrate spectators’ feelings with very little content”). When it turned up at New York’s Collective for Living Cinema just before last Halloween, only a smattering of curious people showed up for the event, and a good handful of these walked out during the first fifteen minutes. To the best of my knowledge, no New York publication deemed the film worthy of review — although an attack on the accompanying short, Godard 1980, which managed to get its title wrong, appeared in The Soho News twelve days later, by a reviewer who smugly concluded, “I wish I could get a crack at re-editing this footage.”

“Personally, I much prefer to show my films in provincial places,” Jost told me in Hoboken a couple of days later, interpreting the Stagefright walkouts as New Yorkers being trend-conscious and fad-oriented. “I’d rather do a show in Omaha, because I feel people are more receptive there. It’s the contrary of what people say.”

3. Filmography (includes only films with available prints, all available from Light Communications, P.O. Box 315, Franklin Lanes, NJ. 07417): 1964 — City (short). 1967 — Leak, Traps (shorts). 1968 — 13 Fragments & 3 Narratives from Life (short). 1969 — Susannah’s Film (short). 1970 — Fall Creek, Flower (shorts). 1971 — Primaries; A Turning Point in Lunatic China; 1, 2, 3, Four; Canyon (shorts). 1972 — A Man is More Than the Sum of His Parts/A Woman is (short). 1974 — Speaking Directly: Some American Notes (feature). 1977 — Angel City (feature), Beauty Sells Best (short), Last Chants for a Slow Dance (Dead End) (feature). 1978 — Chameleon (feature). 1980 — X2: Two Dances by Nancy Karp, Lampenfieber, Godard 1980 (shorts). 1981 — Stagefright (feature).

4. My own first encounter with Jost’s work came when I saw Speaking Directly at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1975, which I wrote about at some length-along with Jean-Marie Straub’s Moses and Aaron, Michael Snow’s “Rameau’s Nephew” by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen, and Chantai Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai de Commerce-1080 Bruxelles (it was a meaty year) — in the Winter 1975-76 Sight and Sound. Made in Oregon and Montana, it’s a materialist exposition of all that the act of filmmaking entails; I can think of no other film like it. As a radical critique of America in the early Seventies, it is as essential a document, in a way, as the collectively made Winter Soldier (1972) — a straight record of the confessions of war crimes given by American veterans back from Vietnam — although the experiences it bears witness to are distinctly different. (Jost was imprisoned in federal custody from March 1965 through June 1967 for draft resistance.)

At the same time, I had certain doubts about Jost’s self-willed isolation as it came across in the film. Writing from the vantage point of an American who had been living abroad for six years and who had already been deeply affected by different attitudes toward collectivity which I’d been exposed to in Paris and London, I was at once attracted to and repelled by Jost’s entrenched, lonely position, which seemed imbued with a cracker-barrel spirit that reeked of Thoreau as well as Mailer. As I put it in Sight and Sound:

“I’m wary about the lure that can be exerted by this brand of all-American confessional — the note of cranky individualism which dictates that all the most well-worn discoveries have to be reasserted anew, like home-made appliances, as if no one had ever thought of them before. It’s the precise reverse of that assumed tradition of several centuries, languages, and ideologies lurking behind every gesture which I find in Straub/Huillet. An American and contemporary of Jost, I’m constantly tempted to indulge in this rhetoric — what else am I doing now? — which may give me a high tolerance for it, extended further by a familiarity with the lifestyles and idioms.”

5. The strange fruit borne by this maverick stance in Stagefright belongs to no acknowledged filmic or theatrical tradition save the magical, yet Jost clearly intends the first section of it to be a “kind of history of mankind and the development of consciousness.” No fooling; and as Jost describes it all, it’s very schematic. What follows is his edited description (with my added interjections):

“You see the woman’s body — egg-shaped, beginnings, right? Then she sort of stumbles around and finally get up on her feet, and by the end of the sequence she’s got her body under control, and she knows it and she smiles and she walks off-screen.” (A man suddenly enters the frame from another direction as she exits, playing with our sense of spatial balance and perspective.) “Then it’s basically the same thing, but dealing with facial expression. First, he’s sort of spastic, then he goes through some elementary expressions, like fear and surprise. Then he walks off, and next you see this actual mirror image where he smiles and frowns to himself. The hand comes in, the camera drops down — I wanted to suggest that expression takes some kind of self-consciousness. But the mirror itself doesn’t produce a dialogue or drama.

“In the next shot you see his face on one side and his infinitely repeated image in a mirror on the other side…. Then comes a mock mirror shot when he smiles and frowns at once, and you get the introduction of conflict. You no longer get a mimicking, but a disagreement.” (After the same actor applies paint to his face, there’s an enormous close-up of his mouth making lip and then guttural sounds, again moving towards greater muscular control.) “I like the very end, when the camera pulls back and his expression really looks like a Francis Bacon character. Then he’s got clothes on — another level of consciousness and repression at the same time.” (Eventually he pulls out a book and reads a Serbo-Croatian myth.)

“Then you go to the alphabet that you hear in different languages and then see in animated figures-again, starting from the earliest ones and going up to the story of Cain and Abel, in Hebrew.” (Blood — or, rather, Godardian red paint — splatters over the Hebrew text, and there’s a dissolve to a close-up of a woman whose face bears an animated cartoon of changing make-up while one hears an audience working itself up into rhythmic applause. End of section.)

It seems to me that Stagefright is your first film that isn’t about America.

Yeah, it’s the first one that isn’t dealing with a specifically American background or context. It’s not dealing with the German one, either — it’s dealing with the universal one. It’s not a pretty picture, I agree…. I was just trying to deal with a more primal form of politics. Most people wouldn’t refer to it as politics, but to me it is. If the prime human story is that we murder one another, that’s definitely a political story — but I was trying to phrase it in more primal terms, that this is something having to do with some very fundamental quality of the human species. And I was trying to deal more on those levels and deal with it so that the viewer received it the way you receive primal things — more on the subconscious level.

That somehow seems more Germanic than your other movies.

Well, in a very real way my politics have changed. Hopefully, they will continue to change as I learn more things.

6. “In all my films, I’m always testing the limits of the audience. In Angel City, it was the part where he picks the jigsaw puzzle apart and gives you a very frontal lecture about what you get when you get a story. He tells you what the etymology of the word ‘story’ is, that it comes from ‘history,’ that its origins mean ‘to know.’ Then he gives a lecture about how story — as we think of it, fiction-means knowing the wrong things. Like, Rexon is a phony company when we should talk about Exxon, the real one, right?

“Then he walks offscreen, and you just have this rather beautiful but barren shot of the blue of the swimming pool, with a woman’s corpse laying on the ground. And that’s the point that’s hardest for audiences, for two reasons. One is that they’re being shown a long, static shot where the lead actor [Bob Glaudini] walks offscreen, and meanwhile they’re getting a lecture about something they don’t want to hear about. They don’t want to hear about the real names, or somebody telling them that they don’t want to hear.”

(Angel City — a comic hard-boiled detective story intermixed with an elaborately detailed social, political, and economic critique of Los Angeles — cost a little under $6,000 to make. Jost’s omnipresent gallows humor, extending to such sequences as an actress, who later becomes the corpse beside the swimming pool, undergoing a screen test for a Hollywood remake of Triumph of the Will, or a TV commercial for Rexon in which the supposedly benign president walks casually along a beach, is reflected in Jost’s own frequent laughter, which some find unsettling. The hero of Last Chants for a Slow Dance, played by drama teacher Tom Blair, exhibits a more advanced case of the same manic, inner-directed cackle.)

7. Are all your films distributed by you?

Yes, and it’ll remain that way. There are distributors in America who would now like to handle my films. Unifilm wanted to take them all. But then I asked, “What are the terms?” “Oh, you provide the prints, we take sixty percent.” I said, “How many bookings can you get me a year for all four features?” “Twenty-five.” Well — I can get on the phone and do that in a week. There’s no distributor in America who’s willing to take me until maybe I’m on the cover of Time Magazine or something. [Laughs.] Then, all of a sudden, I’ll become of interest. Which I find embarrassing to some degree. I mean, there’s no reason why Last Chants for a Slow Dance shouldn’t book as well as a lot of Fassbinder. It’s certainly no less accessible.

(I agree. At once the easiest and most disturbing of Jost’s features, and to my mind the best, Last Chants conceivably gets closer to the mentality of the alienated and seemingly motiveless killer than either Mailer or Capote. Broken up into extremely long takes — some of them accompanied by original country-western songs, written and sung in part by Jost himself, which are a lot more authentic than those in Nashville — the film chronicles the aimless wandering of Tom Bates in his truck around Montana, stopping only once to see his embittered wife Darleen, living on food stamps, who informs him during an ugly fight in front of a bathroom mirror that their two accidental kids are soon to be joined by a third.

Supposedly unable to find a job, although we never actually see him looking for one, Tom is cackling away to a male hitchhiker in the opening scene about how he “can smell pussy a mile away.” When he asks, “Hey, you got pussy waiting for you?” and the younger guy responds uneasily, “I got a girl — I don’t think of her like that,” Tom starts to get pissed off, gradually working himself up into a rage: “Fella, all girls are pussies…. You ain’t one of those funnies, are ya?” Before long, he’s ranting that he’s paid for his truck with his own money, doesn’t have to give anybody a lift if he doesn’t want to, stops, and asks the hitchhiker to get out. Throughout this one-take sequence, the camera, after focusing on the moving highway, pans over to take in first Tom and then the rider as well; the following long take pans between Darleen in front of the bathroom mirror and Tom standing beside a door behind her…. After two encounters in his travels — with a hippie and a woman he picks up in a bar — he winds up killing a man he encounters on the road with car trouble, for no apparent reason apart from the pretext of taking his wallet.)

8. It seems to me that Last Chants is one of the few films that combines elements of structural filmmaking with a whole other tradition that’s more verbal and is closer to someone like Godard. And the structural and narrative aspects set up a very interesting tension between them in relation to things like duration. I’m curious, in any case, what structural films you’ve seen and how you relate to them.

I’ve hardly seen any. What little I’ve seen strikes me as technical exercises, so I end up not being too interested — or I’m interested only if there’s some technical thing I can learn from it.

Have you seen any of Michael Snow’s films?

Just two days ago in Pittsburgh, I saw a reel of The Central Region, and then I saw Wavelength for the first time.

Did they seem like technical exercises to you?

Well, I didn’t get bored with Wavelength, but I also didn’t think it was all that wonderful a film. A lot of the visual intrusions struck me as arbitrary, just sort of fucking around, mainly to maintain your interest visually– all those filters and multiple printing things. It occasionally got a very striking visual effect, but it struck me as arbitrary.

What about the narrative intrusions?

Well, they were there, but they were very skimpy, and then on another level they weren’t believable, because the acting was so amateurish. It was very crude that way. I mean, the idea was interesting, and somehow, cumulatively, you do end up watching it for forty-five minutes. But I was surprised, after reading about it, by what I considered the sort of sloppy way it was done. All those flashes and the filters going over it were a lot cruder than I’d thought might be there. About the first reel of The Central Region, I dunno. It reminded me of a shot in Speaking Directly, the 360° landscape. And I liked it — it was very sneaky as it changed your perspective. I remember having read years ago about those jumps that occur when they changed magazines. I really wish I could have put a 7,000-foot reel on the camera. I find the cuts conceptually very disruptive. And I appreciate the technical problem, although he could have dissolved them and masked them somewhat.

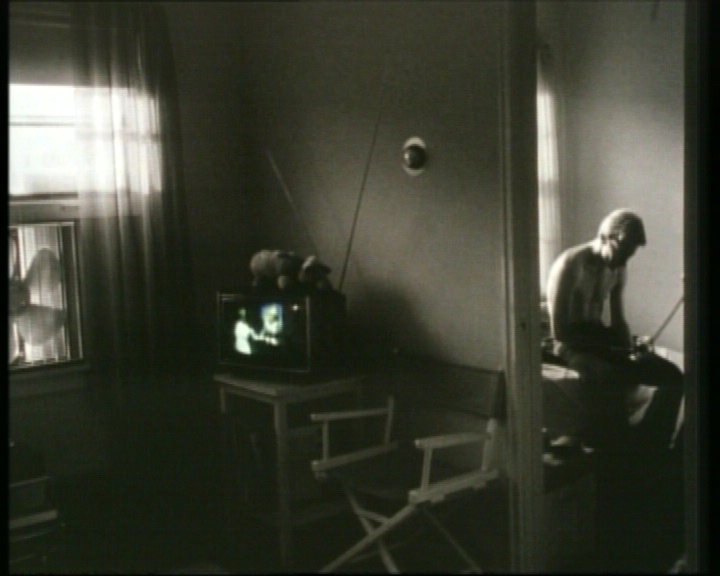

I’m curious about two sequences in Last Chants in which you hold a particular fixed image for a long time. One’s in a roadside diner, and the other’s in a room with a TV set and adjoining bedroom. I’m interested in how you arrived at these sequences and what sort of function they have for you. For me, they both stretch and manipulate the narrative-illusionist precepts of the film in a very interesting way. (I like what Noel Carroll wrote about the film, which applies especially to the latter sequence: “Jost’s strength in this film is his ability to portray the experience of time of the lumpenproietariat who is outside the regimented rhythm of work and sleep, who lives without directions, schedules, and goals.”)

To me, both sequences fall into a broader overall plan for the film, which was that it should start off seeming to be in some sort of realist mode. I wanted to start off with that and then slowly push the viewer off that axis. The first significant place where that happens is the cafe shot, which is a black-and-white shot with the word “cafe” in red, done as a multiple printing. I shot the black-andwhite shot, and then I slept in the place overnight and shot the red cafe neon sign that was in the background, although in the picture it reads as being in the foreground. I knew it would create confusion and be an ambiguous image. Part of the reason I did it was I found it was going to be a relatively long take, and I have to throw in a little spice in the image to make you go with it. As it turned out, the improvisation that the actors did [a scene between Tom and the hippie] was quite funny, so probably it would have held without it. But for a longer strategy in the movie, it was the first step toward throwing it off this realist mode.

Then it goes into a bar sequence, then the couple go up the stairs-which is a multiple-image thing where their image and their shadow become indistinguishable. That’s just a short shot, but it’s usually one that’s quite effective; I watch audiences, and one can just see this little ripple going through that says, “What is this?” Then they go in the bedroom, and here the strategy was on several levels. I knew it was going to be a very long shot-it’s around fourteen minutes. There’s a color TV on one side (the left) in a black-and-white image, and you can hear the track of The Johnny Carson Show, or whatever it was-so you’re listening, and it’s kind of interesting, and at the same time you’re subconsciously trying to look around the door on the other side of the set so you can see them fucking. (As it is, one can see only their feet.) Also, where the TV is situated, if you didn’t have a wall there, that’s where their heads would be. That was like a discreet metaphor for what their mentality was-this is the culture they live in. And within the same shot, there’s also this compression of time, because it starts off at night, and within the same shot, although the TV program is continuous, it’s morning.

That’s one of the things that reminded me of films like Wavelength. How did you do that?

It’s ABC-rolled. One roll is nighttime black-and-white stock, one roll is daytime black-and-white stock, and they’re dissolved together. The third roll is the color TV. All I did was put a black piece of paper over the color TV while I shot the black-and-white. Then I blacked out the room at night, turned on the TV, and just shot it.

The intriguing thing is that you get two different time scales.

Yeah, there’s the continuous take of the TV, which is fourteen minutes, and then the rest, which is twelve hours. You see them fucking, and then there’s this real slow ninety-frame dissolve, and the light slowly fills the room, and the bed’s now different; he’s sitting on it and making a telephone call, she’s in the bathroom, and you can hear water running. Then when they come out and pass in front of the TV set while it’s still on, it prints through them, and they turn into ghosts. To me that had a kind of literary meaning, because in a sense they’re not there, mentally.

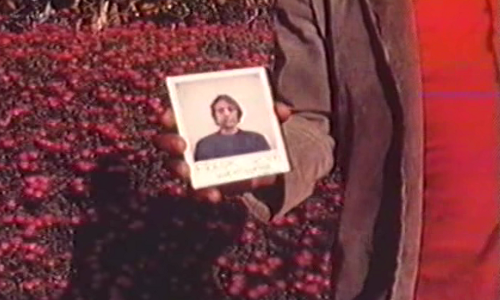

But it was also part of the strategy to keep pushing further and further away from this realist mode. So by the time he leaves her house, this whole thing with the mug shots (Tom looks at and reads “Wanted” notices in a post office, although we see only the notices and hear him offscreen), and writing his postcards (again, in close-up, to Darleen), and the rabbit being killed (in excruciating closeup this time with no discernible relation to Tom), all of that has no plausible relation to narrative logic. What I was trying to do was put you inside the guy’s head rather than have you outside looking at him. So it was basically a step-by-step process away from a realist mode and getting you into a psychic mode of some sort.

I tried to make an honest picture of a small segment of American society. It was definitely an outgrowth of my two years in prison, where I met lots of people like that. And I’m interested in those characters. It has some connection to the Gary Gilmore case, which had happened the previous year.

9. (Chameleon, my least favorite Jost feature, brings back Angel City‘s Bob Glaudini, this time playing a Los Angeles drug dealer who tries to convince an artist to execute forgeries for him. Like Jost’s other story films, it has a narrative only in a quasi-deceptive sense; like Stagefright, it seems freighted with a great deal of literary allegory.)

I read somewhere that the initial idea for Chameleon came from a shot which you weren’t able to do in Angel City. It had something to do with color, I think. And I remember the changing color backdrops during the screen test in Angel City.

Yes, and you see the same thing in the make-up shot in Stagefright. Actually, I think what you’re talking about is something I wound up not being able to do in Chameleon, either. I was talking about the scene in the art gallery [with Gene Youngblood], where each shot has a different color. And originally what I wanted to do was have a continuous take, where the printer would step you through the spectrum. And the reason I didn’t do it was because the continuous take wasn’t strong enough on its own, and I had to cut some flat spots out of it. Also, I probably would have had to scream bloody murder at the lab I was with, to go through a light change every forty frames. Because you could gradate it so there would be no sense of steps, it would just take you right through the spectrum. The lab I’m working with now in San Francisco could do that.

10. When Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin came to the U.S. with Tout va bien in the early Seventies, Jost arranged five west-coast screenings and drove them to each one, after picking them up in the Seattle airport. Godard saw three of Jost’s shorts in Eugene — Primaries, A Turning Point in Lunatic China, and 1, 2, 3, Four — and wound up forcing the San Francisco Film Festival to show them right before Tout va bien. Later, a local newspaper quoted him as saying of Jost, “He is not a traitor to the movies, like almost all American directors. He makes them move.” To the best of my knowledge, Godard remains the only internationally well-known filmmaker, living or dead, whom Jost respects, at least as a filmmaker. (He has supported several lesser-known filmmakers in both America and Europe.) Significantly, when Jost was initially helping to set up a film project with Nicholas Ray and Wim Wenders in 1979, which eventually became Lightning Over Water (see Jost’s article in the Spring 1981 Sight and Sound), Ray had already seen at least one of Jost’s film, Last Chants, but Jost had not recalled seeing anything by Ray.

The seventeen-minute Godard 1980, produced by Framework Magazine in England, shows Peter Wollen and Framework editor Don Ranvaud interviewing Godard, who, to their consternation, backs away from endorsing his own Dziga Vertov Group films and some of his other earlier practices: “For a while, I made movies for other directors, or people who wanted to be directors, who were my real audience…. Loneliness could be good, but isolation is not so good.”

“My experience with Godard is that he’s a lot more mellow than he used to be,” Jost told me in Hoboken. “He’s much better with audiences in answering questions — he doesn’t get sucked into stupid arguments that aren’t going to help anybody. I think he’s learned a lot. Like I know when Sauve qui peut (la vie) went to London, a lot of people were upset, because they were still sitting there theorizing in a dry academic way about things that Godard had already said goodbye to, eight or ten years ago.”

11. At the Collective, you were very critical of what Godard’s interviewers were saying. Are you critical of what Godard says also?

Well, I just feel like — I’m a filmmaker, and I can sympathize and understand a lot more what Godard’s situation and thinking is. But as it was, he wasn’t getting asked good questions, because Don and Peter had pigeonholed him. And they were too much in awe of him. He’s just a human being; if you want to ask him a question, you don’t have to apologize about it before you ask it. [Laughs.]

There’s one moment that’s quite striking, when Godard says that even though he hasn’t been to Vietnam and hasn’t been under a tank, he’s been in a Pans traffic jam. And the moment he says this, what seems to happen is that Don and Peter become, in effect, members of a bourgeois audience responding to a Godard film: they’re embarrassed, shocked, speechless.

Well, they were taken aback. And then Peter says, ‘There are some ways in which it’s the same, and there are other ways in which it isn’t.” To which Godard says, “For me it’s just the same.” And I put that in because I think it’s provocative — especially so for people who have these political brackets that they’re operating in. All he was saying was that, with the subjective experience of being under a machine, it doesn’t matter where it is — if you’ve been under it, that’s what it’s like.

I hear this interview really affected Peter’s opinion of Godard, for the worse.

Well, there’s another part of that, too. Because he and Laura [Mulvey] went out to dinner with him, and he didn’t say anything.

I hear that he did the same thing in New York with David Denby. It makes sense. As far as I can tell, Godard isn’t especially friendly or warm to critics who consider themselves stars.

What Peter and Laura wanted to do was sit down and have a big theoretical conversation, and I don’t think Godard gave a shit.

12. What are we going to do about Jost? One critic of my acquaintance who hates his work has a simple solution for dealing with his combined brilliance and asocial tendencies. She assumes that he steals his ideas from other films, then lies when he claims that he hasn’t seen those films. According to this argument, there’s a lipstick scene in Angel City that’s a direct lift from Flaming Creatures, and the black studio space of Stagefright comes straight out of Le Gai Savoir.

I think that Jost tells the truth and hasn’t seen either of the above films — which doesn’t exactly prevent his work from remaining problematical, either. (In Hoboken, where these issues seem to matter less, he admitted that the opening shot of Godard 1980, which frames Godard from behind, comes directly from the opening of Vivre sa vie.) Jost openly admits that all his films are mainly part of a learning process, that he wants to get a foothold (or even a toehold) in Hollywood, that Angel City and Last Chants, and Chameleon were all partially made to demonstrate that he could make well-acted and attractive-looking story films for practically nothing, that his ultimate goal is to make “essay films for mass audiences.”

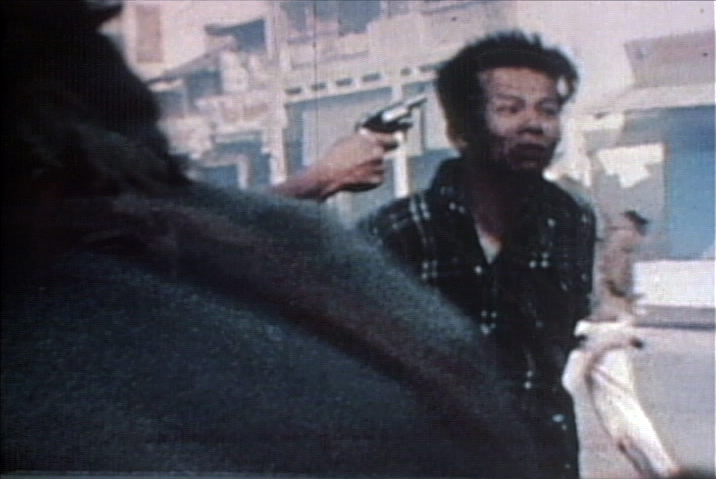

Toward the end of Stagefright, after a lot more magic and allegory and reflections about acting, an actor gets a pie thrown in his face. The sequence slows down until it becomes a meditation on a nearly static image (pie-in-the-face) that seems to last forever. After one feels ready to scream and is ready to howl for blood — without ever looking away, for Jost is cunning enough to hold one’s interest with the visual tease of quick intrusions, like a stopwatch and a screwdriver that enter and exit the frame — Jost suddenly cuts to another shot, taken directly from a 35mm print of Hearts and Minds. It’s footage of a Vietcong suspect being shot at close range through the head and is one of the most powerful and shocking eruptions of violence I’ve ever seen in a film. Like the killed rabbit in Last Chants, it both gratifies our desires for meaning and action and shows the resultant blood on one’s hands in the process. As long as Jost goes on making more films just as truthful, I don’t expect him to win any popularity contests.