From Cinema Scope no. 91, Summer 2022.

Apart from those few who managed to escape from totalitarian regimes and occupied countries, most North Americans know as little about living under a dictatorship and/or in an occupied territory and what that entails as I do. For the past two decades, I’ve been periodically arguing that progressively minded Yank cinephiles missed the boat in the ’60s and ’70s by focusing too exclusively on Godard, Bertolucci, and similarly oriented Western leftists while ignoring the far more politically and formally radical inventions of Eastern European cinema by Chytilová, Jancsó, and Makevejev, among others — an avoidance that largely came about because we didn’t know more about what was happening in those parts of the world. A comparable limitation in the 1930s and 1940s led critics such as Dwight Macdonald to focus far more on Eisenstein and Pudovkin than on Dovzhenko, and as I’ve argued elsewhere, even a passionate Dovzhenko fan such as James Agee was fairly clueless about the political difficulties this Ukrainian filmmaker was having with the Russians.

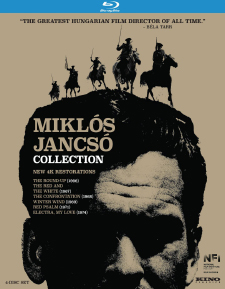

Bearing this shared ignorance in mind, all of the most striking releases I’ve encountered this spring —Serge Loznitsa’s Donbass (2018), on DVD from Salzgeber & Co. Medien GmbH; Radu Jude’s Uppercase Print (2020), on DVD from Big World Pictures; and The Miklós Jancsó Collection from Kino Lorber (four Blu-rays, including half-a-dozen features from the 1960s and early 1970s and several shorts) — offer veritable crash courses in filling in many of the gaps. Some of this comes in the form of factual information, some in terms of art, and sometimes we may not even be sure which is which. In the Jancsó collection, for instance, the wonderful audio commentaries affixed to all six features are as bountiful in some ways as the films themselves, and sometimes the art and craft of these critical explications rests in their teasing out the less obvious factual information (at least to non-Hungarians) that’s embedded in the Jancsó works. Given that Jancsó’s Hungarian films of the ’60s and ’70s, unlike the contemporary Loznitsa and Jude works, were made under constraints that made allegory, myth, and a sense of pagan ritual virtually essential as indirect routes toward political expressiveness, they can’t be judged or described in the same fashion; they need more unpacking, and fortunately, the Kino Lorber set has amply provided this.

The most immediate of these releases, in terms of newsworthy relevance and sheer visceral and emotional impact, is Loznitsa’s pulverizing Donbass, which is about what Russia (that is, certain Russians) was/were already doing in and to eastern Ukraine (that is, Ukrainians and their living spaces) four years ago. (I thank Mark Rappaport for urging me to see this, and should add that his Rock Hudson’s Home Movies [1992] and From the Journals of Jean Seberg [1995] are available now from Kino Lorber, with many spiffy extras.) No less significantly, Donbass occupies the sort of magical cusp between documentary and fiction that many of the best documentary storytellers have excelled in, from Robert Flaherty to Joris Ivens, Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, Roberto Rossellini, Agnès Varda, Françoise Romand, Michael Snow and Peter Thompson. (Perhaps even Frederick Wiseman and James Benning belong in this distinguished bunch — replying to Sight and Sound’s ten best documentary film poll in 2014, the latter memorably nominated “Titanic [Cameron]. This is my only vote: an amazing document of bad acting. And, I might add, all films are fictions.”) And for those who still assign documentary purity to Nanook of the North (1922), it’s useful to point out the often neglected fact that Flaherty’s girlfriend was cast to play Nanook’s wife in the film.

In Donbass, this dynamic is manifested in events that can seem both very real and yet staged for the camera, the various episodes commingling with one another like the stories in a unified collection such as Joyce’s Dubliners or Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio. The collective impact of these stories qualify the film as propaganda, though so too do a good many Hollywood commercial releases and TV news broadcasts. David Walsh of the World Socialist Web Site, for one, has labelled Donbass as right-wing propaganda, apparently because Loznitsa believes in personal property and maybe because Donbass ignores the more Nazi-like Ukrainian separatists who confuse the issue. All docudrama fictions involve certain trade-offs that become especially acute when the material is controversial — so if one is entertained by, say, the freewheeling and adeptly made recent Swedish miniseries Clark, about the exploits of bank robber Clark Olofsson, one has to weigh the giddy high spirits of the anti-establishment slapstick against the appalling sexism with which the hero’s fantasized sexual exploits are depicted and celebrated.

Whatever demurrals might be offered about the simplifications and evasions of the various episodes in Donbass, they still made it far easier for me to understand some particulars about what’s happening now, four years later, in Ukraine. For those who prefer streaming to purchasing the DVD, my brother Alvin informs me that you can access Donbass at easterneuropeanmovies.com ($5 for a one-day pass).

How much do most of us know about living under constant surveillance? My own innocence was such that the only time I ever visited a Communist dictatorship — a few hours spent in East Berlin in 1989, a few months before the Wall came down — I couldn’t understand why everyone in the cafés and bars I visited spoke in murmurs and whispers. Radu Jude and Gianina Cărbunariu’s Uppercase Print, a film version of Cărbunariu’s documentary play derived from the police records of the Romanian city of Botoșani during the 1980s, is the best corrective I’ve yet encountered for this blind spot.

In 1981, chalked graffiti in uppercase letters started appearing in public places in Botoșani, extolling such things as “freedom” and “justice” and “free unions” (as in Poland). The police investigation, which involved handwriting analysis and recorded interrogations of suspects and possible witnesses, eventually zeroed in on Mugur Călinescu, a teenage boy who was arrested and who immediately confessed to writing the graffiti — although the fact that he refused to express remorse about his deeds led to extensive wiretapping of phone calls made at his home and secret recordings of both his conversations with his parents and a meeting of his teachers and other school authorities. Even the fact that he sometimes listened to Radio Free Europe (before his radio broke down) was subject to endless interrogations and alarmed speculations.

Many of these police reports, interrogations, and conversations are presented in Uppercase Print in a very striking and deliberately artificial studio setting of adjoining stages that resembles a brightly coloured and fluorescent comic strip; the conversations of the boy with each of his parents are played out in front of a gigantic TV screen, for instance. These are basically stationary recitations by the actors, whether they’re seen in close-ups or in long shots, and the only striking movements come from the camera traversing the enormous set. The delivery of lines is equally artificial, toneless and uninflected in a way that recalls Brecht’s instruction that the actors should seem to be quoting — as indeed these actors are, verbatim, from the police reports, easily demonstrating that the facts of the case are awful enough on their own and have no need for dramatization (the precise reverse of Loznitsa’s strategies).

Alternating with these presentations are TV clips from the same period — commercials for cars, cosmetics and tourism, government pronouncements and pageants, cheerful displays of toddlers dancing, full-scale musical and opera performances—most (if not all) of which provide a sarcastic counterpoint to the police reports (which eventually conclude with the police’s justifications for all their surveillance and their getting the boy’s schoolmates to squeal on him). Sarcasm, a recurring emotional register in Romanian art cinema in general and Jude’s work in particular, gradually appears to become the only possible response to the collective weight and impact of the material.

I’m watching these DVDs and Blu-rays at a time when American would-be dictators and the TV stars promoting them are devoted to eliminating voting rights and reproductive rights to millions of people at the same time that the Russian dictator they’re backing so doggedly is busy destroying the country of Alexander Dovzhenko and millions of his successors. In this context, the lessons available from these talented descendants of the crippled casualties of the Austro-Hungarian Empire aren’t valuable simply as diatribes or warnings, they’re also outrageously beautiful as works of art — that is, works of particular kinds of art that we’ve customarily been taught to ignore or overlook. A similar avoidance often applies to those singular and troubling works by Eastern European directors commenting at least partially on our side of the planet, e.g., Emir Kusturica’s Arizona Dream (1993) or Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) and Sweet Movie (1974).

It’s not surprising that North America is far behind France and the UK in paying some heed to the huge legacy of Miklós Jancsó (1921–2014), surely the greatest of all Hungarian filmmakers. About six years ago, the Cinémathèque française and Clavis Film released a Jancsó DVD box set with ten features from the ’60s and ’70s and a good many extras, including a feature-length documentary by Jean-Louis Comolli for Cinéastes de notre temps, a booklet with essays by Martin Scorsese (who also briefly introduces The Miklós Jancsó Collection), Marina Vlady, Noël Simsolo and Jancsó himself, and many short films. And Second Run Features, over roughly the same period, has been offering us many superb editions of Jancsó features on both DVD and Blu-ray.

In her persuasive and highly polemical audio commentary to Jancsó’s The Confrontation (1969) for the new Kino Lorber set, Kat Ellinger dates the time and place that the West started turning its back on Eastern European cinema as the Cannes Film Festival in 1968, which was shut down largely through the efforts of Godard and Truffaut — who in effect decided that the rights of French workers mattered so much more than the exposure of Eastern European films that the festival had to be cancelled, thus preventing many features (including The Confrontation) from being shown. Even though I happen to find The Confrontation less thrilling than the other two Jancsó colour films included in the set — the 1971 Red Psalm (with another audio commentary by Ellinger) and the 1974 Electra, My Love (with an audio commentary by Samm Deighan, who also lends her thoughts and voice to the 1969 Winter Wind) — it’s the only political musical of Jancsó’s that I’ve seen with a contemporary 20th-century setting, which makes it all the more lamentable that it wasn’t allowed to become part of the French left’s rallying cry.

One reason why I’m focusing so much on these six audio commentaries is that so much historical and contextual information (as well as critical insights) are imparted in them that an entire course in Jancsó could easily be constructed out of their contents. Most of us will have to bone up on certain aspects of Hungarian history and culture in order to appreciate what he’s up to here beyond the films’ more abstract qualities, and the commentaries in this box set are designed to help us in that endeavour. Perhaps the most impressive of these is the first, by Michael Broke on The Round-Up (1966), which displays so much expertise that it made me dizzy at times, ready with my pause button to declare “Enough!” yet still too entranced to press it. But Jonathan Owen on The Red and the White (1967) — the first Jancsó film I ever saw, during its initial commercial run in New York — isn’t far behind, and the two commentaries apiece by Ellinger and Deighan are full of other facts and perceptions.

For all their differences, the half dozen Jancsó features in this package, all of them scripted or co-scripted by Gyula Hernádi, could be described as poetic parables about power and its abuses, constructed like musical compositions out of a choreographed camera in motion and choreographed performers dancing in continually shifting relations to one another. Many of these attractive performers — most often women — appear nude, for reasons that appear to be either politically incorrect or non-existent, but at no point do the proceedings even remotely resemble a burlesque show. (Similarly, many other attractive performers, most often men, appear on horseback, but at no point do the proceedings look like a Western.) The Round-Up and Winter Wind each largely focus on the sort of paranoia that grows out of surveillance, yet the ways such paranoia gets exposed and analyzed bear no resemblance to the artistic strategies employed in Jude’s Uppercase Print. The Red and the White and The Confrontation deal, respectively, with Red troops and White Guards clashing on Soviet territory in 1918 (or 1919, according to Owen’s audio commentary), and Communist and Catholic students debating and defying one another in 1947, shortly after the Hungarian Communist Party assumed power.

For Red Psalm and Electra, My Love — my two favourite Jancsós, both in colour (and the latter in dispersed, Antonioniesque Scope) and both exhilarating mixtures of myth and allegory in a highly sensual form — the assistance of the commentaries by Ellinger and Deighan, respectively, is especially valuable (as much so as Raymond Durgnat’s essay on the former film at Rouge). The 70-minute Electra, My Love (which plays out in a mere dozen takes) is adapted from a contemporary play by László Gyurkó that uses the Greek myth of Electra to compare Agamemnon to János Kádár, the prime minister of Communist Hungary, yet it unfolds in a fantasy netherworld that is neither Hungary nor Greece. In her commentary, Deighan helpfully cites J. Hoberman’s description of Jancsó’s surrealism as “the Theater of the Absurd without the laughs” — a kind of formalist playground of non-narrative pageantry whose sensual and dramatic values redefine what we mean by freedom, pleasure, and spectacle without ever becoming flippant or cynical, thereby persuading us to reinvent ourselves in order to engage with it. On the other hand, Ellinger begins her commentary on Red Psalm with a warning against over-intellectualizing Jancsó and viewing his work too abstractly.

The only serious problem I have with these Jancsó audio commentaries is that it’s impossible to enjoy them and to enjoy the direct impact of a Jancsó film at the same time. One has to approach this box set in separate stages, and as a different kind of spectator each time one enters it.