From the Chicago Reader (February 12, 1988). — J.R.

THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Kaufman and Jean-Claude Carriere

With Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, Lena Olin, Derek de Lint, Erland Josephson, Pavel Landovsky, Donald Moffat, and Daniel Olbrychski.

Before we are forgotten, we will be turned into kitsch. Kitsch is the stopover between being and oblivion. — Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The semibearable heaviness of Philip Kaufman, at least in his last three features — Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Wanderers, and The Right Stuff — is largely a matter of an only half-disguised didactic impulse, a notion that he’s got something to teach us. For a filmmaker as commercial as Kaufman, this impulse becomes worrying chiefly because we emerge from his movies not knowing anything essential that we didn’t know before we went in. We’ve submitted ourselves to a certain intelligence, grandiosity, and slickness, and we may well have been entertained — Kaufman has undeniable craft as a storyteller — but it’s questionable whether we’re any wiser.

There’s nothing at all disgraceful about this. But the suggestion that we’re supposed to be getting something more than intelligent entertainment from a Kaufman film — which seems to hover over every frame like an admonition, almost a threat — leaves an unsatisfying aftertaste. In the case of The Unbearable Lightness of Being — a sexy, watchable, and touching adaptation of Milan Kundera’s novel that is considerably less than the sum of its parts, yet still qualifies as the best Kaufman film that I’ve seen — it may even interfere with part of our pleasure.

The film runs for well over two and a half hours, and is seldom boring, largely because its three main actors — Daniel Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche, and Lena Olin — are unusually skillful and attractive. Sven Nykvist, Ingmar Bergman’s great cinematographer, is director of photography, and Jean-Claude Carrière, who collaborated with Luis Buñuel on his last masterpieces, worked with Kaufman on the script. The movie, in short, has all the credentials that one could ask for, except for the most important one — a commanding and shaping vision of its own. And because it lacks this vital ingredient, the talents of those involved are enlisted to paper over the gaps, as they have done in other middlebrow favorites over the past few years — Day-Lewis in A Room With a View, Carrière in The Return of Martin Guerre, Nykvist and Carrière in Swann in Love, all streamlined triumphs of art direction, costume design, and ensemble acting, pressed to noble Masterpiece Theatre purposes: tasteful, elegant, intelligent, and artistically dead on arrival, embalmed in their own virtue.

Kundera’s novel, which I turned to only after seeing the film, is a pleasurable and easy read, but it’s hard to imagine any mainstream film being made out of it that wouldn’t violate its essence. Structured in some ways like a Kurt Vonnegut novel, it is mainly composed of short chapters and short paragraphs that circle and recircle the plot rather than burrow through it in strict linear fashion. By returning to the same incidents more than once, Kundera introduces fresh perspectives and details each time around, and creates a certain meditative stasis around the characters — an effect that is further enhanced by philosophical reflections about their lives and thoughts that function, in musical terms, like pedal points. Set before, during, and after the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the novel has a lot to say about the complex interactions between the personal and the political, as well as both the interrelationships of and the differences between love and sex, tracing these themes across the lives of four characters and exploring them partially in essay form.

The important thing about these essays is that they aren’t experienced as interruptions of the narrative, but as natural extensions — a purely literary effect that is acknowledged by Kundera himself. He makes this point more than once — that his characters “are not born like people, of woman; they are born of a situation, a sentence, a metaphor containing in a nutshell a basic human possibility that the author thinks no one else has discussed or said something essential about.” By severing them from their literary origins, Kaufman may be making them “lighter” in Kundera’s terms, but his direction makes them heavier than their truncated selves deserve to be; it weights them down with heroic baggage they were never designed to carry.

The hero, Tomas (Day-Lewis), is drummed out of his profession as a successful surgeon in Prague when, after the Russian occupation, he refuses to make a retraction of his previously published critique of Communist political trials. This comes straight out of the novel, but the film pointedly omits Tomas’s later refusal to sign a petition requesting amnesty for political prisoners. In other words, while Kundera carefully shows how (and why) the fundamentally apolitical Tomas refuses to align himself with either Soviet or anti-Soviet forces, Kaufman simply turns him into a standard-issue political martyr — specifically the kind that Americans most readily like and understand.

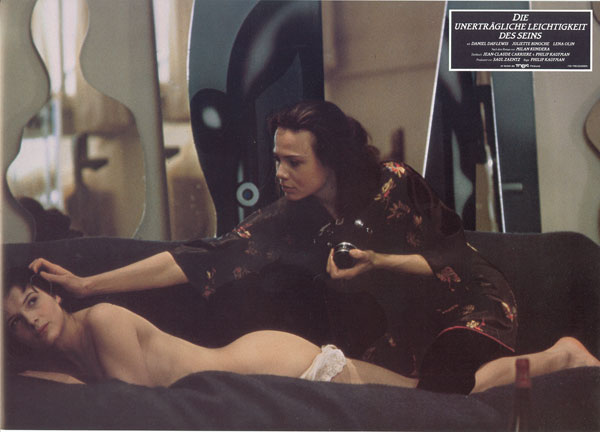

The reasons for this may be technical as well as ideological: the character who asks Tomas to sign the petition is his estranged son by a previous marriage, a character omitted in the film. But it points to an overall simplification and reduction that robs the original of its complex symmetry. Both novel and film follow the lives of Tomas, his second wife, Tereza (Binoche), his sometime lover, Sabina (Olin), who eventually becomes an emigré, and Sabina’s Swiss lover Franz (Derek de Lint), whom she meets in Geneva. But while the book gives all four roughly equal importance, morally as well as aesthetically, the movie more conventionally concentrates on the love story between Tomas and Tereza — the compulsive promiscuity and guilt of the former, the intimidating devotion and dependency of the latter, which are finally resolved when they move to the country.

Making Sabina and Franz more marginal — in effect, characters who matter only in relation to Tomas and Tereza — the film never knows quite what to do with them; Franz, in particular, seems stranded in a semigratuitous Gig Young part, and the movie drops him like a hot potato the first chance that it gets. While we learn of Tomas and Tereza’s eventual death less than halfway through the book, the movie saves this morsel for the very end; and because most of the contrapuntal effect of alternating between different characters and time frames is lost, much of the novel’s meaning goes with it.

The obvious respect that Kaufman and Carrière show for the novel, even while they’re disemboweling it, registers as a kind of tokenism whereby the shards of certain themes are left dangling, as puzzling allusions to the book that no longer have a function of their own. “In the kingdom of kitsch, you would be a monster,” Sabina remarks to Tomas at one point — one of the puzzling details that drove me to the novel to discover what I was missing. The line is initially puzzling in the novel as well, but is eventually clarified by an extended discussion of kitsch that is one of the best things in the book.

Kundera defines kitsch as “the aesthetic ideal” of “a world in which shit is denied and everyone acts as though it did not exist.” Examples in the novel include not only Communist kitsch such as May Day parades, but American kitsch, such as the remark of an American senator to Sabina after she has emigrated to the United States, made while his children are playing in the grass around a stadium, “Now that’s what I call happiness.” The implication that Kundera finds in this comment is that Sabina’s native country was a place where “no grass grew or children ran.”

Whatever Kaufman is out to teach us, lessons in kitsch are not a vital part of the curriculum. As Kundera points out, “In the realm of kitsch, the dictatorship of the heart reigns supreme,” and this is more or less where the film of his book resides as well. Thus a farmer’s pet pig, which has a small place in the novel, is practically given a costarring role in the movie, so that it can be brought on like a vaudeville standby whenever the action flags; add Tereza and Tomas’s adorable mutt Karenin, which matters even more, and one wonders if this isn’t the first R-rated pet movie.

The kitschy musical taste of Soviet officials is pushed to the fore in a scene that has no counterpart in the novel. But as “positive” musical examples before and after this scene, Kaufman gives us “Hey Jude” in Czech (a nice idea, and quite in keeping with Kundera’s passing celebration of the Beatles’ white album) and “Sentimental Journey” played by a fiddler in a village tavern, neither of which is supposed to be perceived as kitsch.

The kitschy leftist political impulses of Franz and an American movie star resembling Jane Fonda — who join an international protest march to the Cambodian border, which is a major episode in the novel — obviously have no place at all in this movie. Kundera’s political defeatism can be either defended or attacked as an attitude formed by the last two decades of Czech history; the point is that Kaufman treats it like shit and pretends that it doesn’t exist.

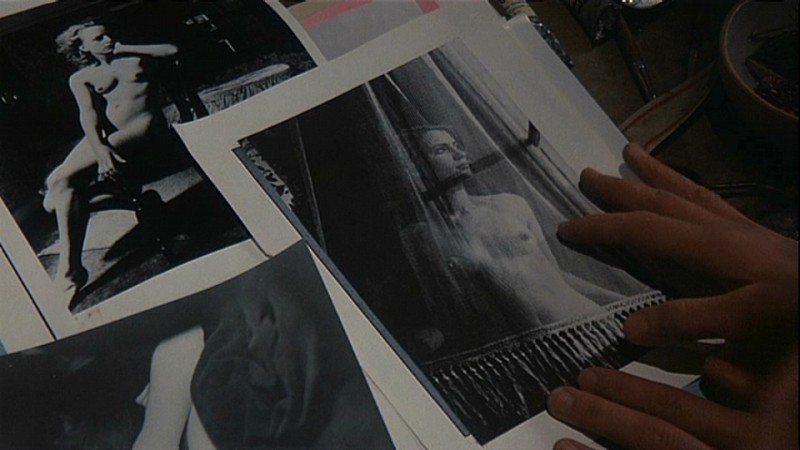

Turning Tomas’s apoliticism into something very American, the movie essentially opts for the love story, gooses up the sex, and introduces newsreel footage of the Russian invasion of Prague so that Kaufman and Nykvist can exhibit their skill in shooting their own matching footage of Tomas and Tereza in the crowds. The technical accomplishment of the latter is impressive. But it is symptomatic of the film’s formal laxness that, like the jokey printed intertitles that appear at the beginning of the movie, this figures as a passing fancy, an incidental set piece and attraction, rather than as an integral part of an overall design.

Admiring this technique is rather like admiring the capacities of Day-Lewis (English), Binoche (French), and Olin (Swedish) to speak English with Czech accents, which they seem to do rather well. It turns us all into gaping tourists rather than thoughtful participants, and the portions of Kundera’s novel that don’t match our preconceptions about the subject slip effortlessly out of sight.