A special sort of Christmas essay from the Chicago Reader (December 23, 1994). — J.R.

Over the past year we’ve been hearing a lot about the theme of redemption in current movies. Actually the seeds of this trend were probably sown back in 1980, when Raging Bull came out, but now “redemption” is becoming something of a buzzword. I recall being taken slightly aback when I heard Harvey Keitel, speaking at the 1992 Toronto film festival, employ the term without any trace of irony in regard to Reservoir Dogs. And since then I’ve been hearing it more and more, mainly in relation to movies associated with Quentin Tarantino (not only Reservoir Dogs but also True Romance, Natural Born Killers, Killing Zoe, and Pulp Fiction) and such varied films as Cape Fear, Cliffhanger, Forrest Gump, The Professional, and even Heavenly Creatures.

What’s surprising is not only the odd assortment of movies in this new canon but those that are automatically excluded. Looking over last year’s releases, one might logically conclude that movies dealing with the spiritual redemption of their lead characters would include, say, Schindler’s List, Little Buddha, Savage Nights, The Shawshank Redemption, Bill Forsyth’s grossly neglected Being Human, and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Blue, White, and Red. But these films are seldom if ever mentioned as having anything to do with redemption. Going further back in time, one could cite all sorts of films dealing directly with religious vocation, from Diary of a Country Priest to A Man Called Peter to The Last Temptation of Christ. But none of them are taken to have any bearing on the discussion either.

It would appear that a willingness to kill people without compunction — presumably shared even by sweet-tempered simpleton Forrest Gump when he goes off to Vietnam — is the main qualification for being “redemption-ready.” A taste for cocaine and heroin and a command of pop-culture references help but are less important. Theoretically the HIV-positive hero of Savage Nights, who glories in unsafe sex and snorts a lot of coke, is a prime candidate, but the fact that he’s French and bisexual seems to make him more problematic. National, ethnic, and sexual identities play a significant role in determining who is elected for redemption.

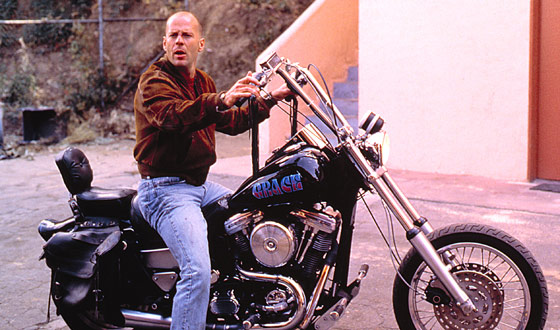

As Janet Maslin has indicated in the New York Times, personalized license plates also count for a great deal. According to her, Bela Tarr’s Satantango is strictly nihilistic because all the characters are greedy and self-centered, but the transcendental Pulp Fiction teaches us something about being redeemed because Bruce Willis — who batters his boxing opponent to death for cash without a trickle of remorse and takes pleasure in hacking away at some nasty hillbillies with a Japanese sword — makes his getaway on a stolen motorcycle with a license plate that says “Grace.” She doesn’t comment on whether a Japanese sword with the word “Grace” on the handle would have done the trick as well, but I suspect it would. Of course, since both the motorcycle and the Japanese sword belonged to the dead hillbillies, I suppose they too could be said to be touched by a certain grace, especially since their favorite pastimes are torture and anal rape of random victims.

I imagine that if the characters in Satantango came across a motorcycle, or a Japanese sword for that matter, they’d steal it too. But because they’re living not in Los Angeles but in a godforsaken hillbilly section of Hungary, they’re denied this option. None of them even has access to a working TV, so they can’t be redeemed by making any passing references to the Fonz or any other American standby. And, assuming that they came across a motorcycle or sword labeled “Grace,” it would still be in Hungarian, and what could be more nihilistic than that?

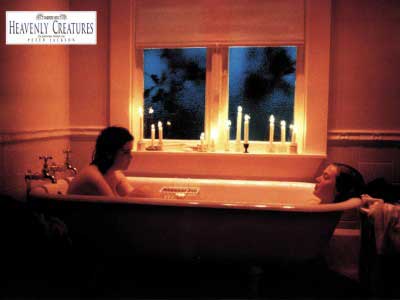

Apparently working-class pride plays a significant role in the new “redemption.” After all, Sylvester Stallone, undoubtedly thinking back to his own Rocky films, employs the term compulsively in interviews he’s given, and the degree to which Tarantino’s scripts and stories are about working-class characters bringing a sense of hip personal style to their lives obviously has a great deal to do with their appeal. One supposes that living in present-day America also helps (though Tarantino’s own pantheon of favorites tends heavily toward French and Hong Kong films dating back to the 60s), and being male is an apparent prerequisite. But if these distinctions are crucial, what’s Heavenly Creatures — which deals with two teenage girls in a middle-class New Zealand milieu during the 50s — doing on the list? These girls don’t snort cocaine or commit mass murders, but together they do kill one of their parents, and they share a cult enthusiasm for Hollywood favorite Mario Lanza. Apparently these facts are sufficient to excuse their national origins and sex.

Not all the sympathetic characters in current so-called redemptive movies, even the more heroic ones, necessarily qualify for redemption. In True Romance I was struck by the degree to which the best scene is also, at least in retrospect, the most morally dubious — something that happens frequently in Tarantino’s pictures. In this scene Dennis Hopper, the semiestranged father of the hero, Christian Slater, is tortured to death by a Mafia drug lord because he refuses to reveal his son’s whereabouts. He adds insult to injury with a racist monologue suggesting that Sicilians are part black because their ancestors were raped by Moors. One might assume that Hopper’s courage and the style with which he defies this villain qualify him for redemption in contemporary terms. Yet Slater never even learns about his father’s death, going off to his Mexican hog heaven with Patricia Arquette at the end without the slightest curiosity about what happened to his old man, whom the viewer is invited to forget as well.

Could it be, then, that one’s age group also has something to do with qualifying for redemption? It seems the young are exempt from damnation in these movies: toward the end of True Romance, Slater and Arquette emerge from a climactic shoot-out miraculously intact, while everyone else in the vicinity gets wiped out. Speaking to Dennis Hopper in the literary journal Grand Street, Tarantino complains about the accidental death of a villain who tumbles onto an anchor in Patriot Games: “As far as I’m concerned, the minute you kill your bad guy by having him fall on something, you should go to movie jail….You’ve broken the law of good cinema.” But judging from True Romance — and Pulp Fiction, for that matter — accidental survival, unlike accidental death, is more than OK; it means you’ve been touched by the screenwriter’s grace.

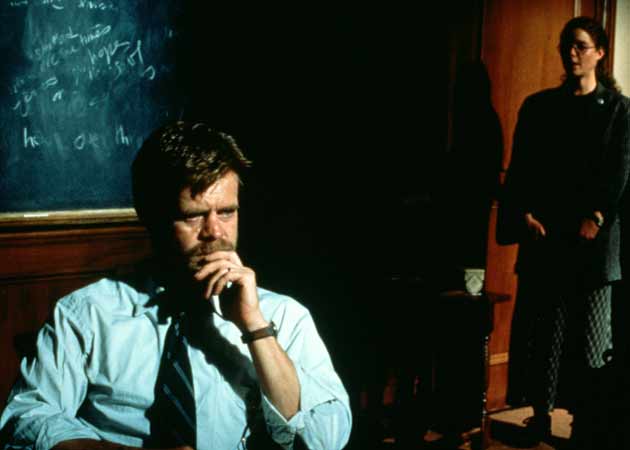

So-called redemptive movies employ a sort of double standard of feel-good ethics analogous to the difference between “bad” and “good” political correctness in the public mind. Bad PC is making the pompous professor in David Mamet’s Oleanna and the female student who charges him with sexual harassment equally detestable — although, according to Mamet on Charlie Rose’s interview show, he finds the two characters equally sympathetic and commendable. (Either way, the movie was destined to be a box-office flop because it obliges the audience to think.) Good PC, on the other hand, to borrow an example from Andrew Sarris, is making Forrest Gump — a white boy from Alabama with a “subnormal” IQ, whose grandfather belonged to the Ku Klux Klan — free of any trace of racial prejudice.

Still, there’s some cause for hope. If we move beyond movies to the recent elections (assuming that there’s an epistemological difference between the two), it would appear that Bill Clinton — unlike Forrest Gump, the characters played by Stallone, Slater, Willis, Travolta, and Samuel L. Jackson, the teenage girls in Heavenly Creatures, and the murderous couple in Natural Born Killers — has been beyond redemption for some time. Fortunately that’s no longer true, thanks to some recent statements by Newt Gingrich. According to him, Clinton is personally responsible for Susan Smith’s killing her two small children in South Carolina, and a full quarter of Clinton’s staff is hooked on drugs. These two facts alone make him a potential double winner in the redemptive sweepstakes; add the fact that he’s a relatively young, currently living American male who comes from the working class and supports the slaughter of third-world civilians and he seems to have nearly all the credentials. He may not have the right kind of customized license plates yet, but like Slater in True Romance he certainly knows when to make reverential allusions to Elvis. So if people believe either or both of Gingrich’s assertions, maybe our own president will finally have the same crack at transcendence currently enjoyed by half-wits, drug dealers, and killers.