From the Chicago Reader (February 17, 1989). I was extremely disappointed in the revised version of this film that was released about sixteen years later, which I also reviewed in the Reader, because I believe it essentially effaced or distorted many of the virtues I found in the original film. (One can find my arguments about this here.) — J.R.

GOLUB

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jerry Blumenthal and Gordon Quinn.

By and large, painting and cinema have always tended to be uneasy bedfellows. To film a stationary canvas with a stationary camera is to deprive the viewer of both the movement possible in film and the movement possible to the viewer of a painting in a studio or gallery. On the other hand, to find a stationary canvas with a camera in motion is to impose an itinerary on the painting in question, thereby limiting the reading of the individual viewer.

While there are a handful of interesting and respectable art documentaries in the history of film, such as Alain Resnais’ Van Gogh (1948) and Gauguin (1950), and Sergei Paradjanov’s recent Arabesques Around a Pirosmani Theme — all three of which significantly happen to be shorts — the overall failure of film to record a painter’s work without recourse to a gliding Cook’s tour or a mincemeat dissection of the work in question has been far from encouraging. Overlooking such uneven biopics as Lust for Life, Moulin Rouge, and the more recent Frida, Wolf at the Door, and Vincent, the challenge of filming a static canvas kinetically has defeated practically everyone.

I’ve never made it all the way through Henri-Georges Clouzot’s ambitious 1956 documentary feature Le Mystère Picasso (known in English as The Picasso Mystery or The Mystery of Picasso), which is currently available on tape, but the opening of that film strikes me as being a veritable checklist of wrong moves. The film opens with an arty black-and-white shot of Picasso sitting brooding across from an easel and canvas on the other side of the room as an offscreen narrator intones, “One would give anything to know what went on in the head of Rimbaud when he was writing ‘The Drunken Boat,’ or in Mozart’s head when he was composing — to know the secret mechanism that guides that creator in his perilous adventure. Fortunately, what is impossible in poetry and music can become a reality in painting.”

This scene is eventually succeeded by the film’s main course, in color — an extended process that allows us to follow Picasso’s hand from the reverse side of the canvas, yielding a sort of animated evolution of a painting, accompanied portentously by classical music. But far from a revelation, this spectacle is only further mystification. And if we assume that the main thing that went on in Rimbaud’s head when he was writing “The Drunken Boat” was precisely “The Drunken Boat,” the implication is that Clouzot’s foray into Picasso’s methods is an equally tautological exercise.

One of the great, refreshing achievements of the 58-minute documentary Golub, which mainly concentrates on the conception, execution, and exhibition of a single painting by Leon Golub, is that it assumes at the outset that there isn’t any mystère Golub to be unveiled or penetrated. Made by the sophisticated Chicago-based collective Kartemquin, which has mainly concentrated in the past on grass-roots political struggles, the film takes on none of the hushed reverence or monumental pretension that usually accompany this culture’s alienated approach to the act of making art. Eliminating art critics entirely from its purposeful discourse, it offers as its main spokespeople Golub himself; Nancy Spero, his wife and a fellow artist; a museum director; and a number of ordinary spectators in various galleries, all of whom prove to be more than adequate to the task.

The fact that Leon Golub is a politically motivated painter is undoubtedly part of what led Kartemquin to his work, but while the film never loses sight of the political significance of Golub’s art, its treatment of Golub’s form, style, and methodology is never reductive. Golub is an artist who recalls a precursor from an earlier generation of American realist painters, Ben Shahn, in the angular sweep of his human figures and the broad stretches of space that surround them, as well as in the direct, graphic address of his social subjects. He is unusually articulate about his aims and methods, and some of the film’s strength derives from its willingness to let him talk.

This is not to imply, however, that Golub is just another talking-heads documentary. Before the painter even appears, there is a prologue (of less than three minutes) of more than two dozen shots — a remarkable sequence that manages to give us a multifaceted precis of what is to follow without providing any kind of obstacle course for the audience.

This rapid, exquisitely timed montage mainly consists of fragments of Golub paintings, gallery spectators, and TV news clips. Most of the shots feature darting camera movements (mainly pans and zooms), and all but the first are accompanied by a single, sustained, growling bass-clef chord from Tom Sivak’s highly effective and functional score; but the filmmakers arrange these elements in a logical and fluid pattern rather than a confusing jumble. The TV clips, which recur throughout the film, serve to dramatize Golub’s treatment of physiognomies, body positions, and power relationships that exist all around us in the world, but they never suggest literal or obvious duplications of the world in Golub’s work; they suggest, rather, that the faces and postures seen in the paintings and those glimpsed in Vietnam, in Nicaragua, at the Iran-contra hearings, and elsewhere belong to the same family of images.

The very first shot of Golub, an unorthodox substitute for a credit title, provides interesting insight into directors Jerry Blumenthal and Gordon Quinn’s highly compressed method. Lasting only nine seconds, the shot features an off-the-cuff camera movement that follows a woman on the street going down and then up two separate shallow flights of steps as she passes an enormous sign bearing the word “Golub” in black letters against an Indian red background. The woman begins below the sign at screen left and ends up on a parallel plane with it at screen right, which suggests a movement away from the standard hierarchy of painting over spectator to a position in which they’re accorded an equal footing, like two individuals in an eye-to-eye confrontation. The Indian red background, moveover, introduces us to the background of the Golub painting that most of the film is concerned with — a color that manages to suggest at the same time blood, earth, and violence.

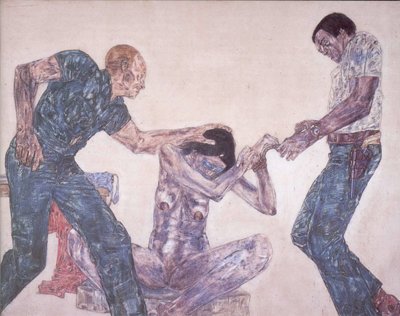

Most of the remainder of the film concentrates on Golub’s production of a single large canvas. The camera follows him through a detailed series of steps, with Golub himself most often providing commentary about the various decisions involved while he works. Looking for pictures of figures in certain positions in his massive file cabinet of photographs, he comes up with two key photos — one of a man whose face is being pushed into the ground, the other of a man stooping who can be used as a model for the man who is doing the pushing. Golub tapes these two photos to different sections of a huge blank canvas on his studio wall and then begins to sketch his two figures below them in chalk, revising certain details of posture and position as he draws.

He deliberates on whether the aggressive figure should be bare chested or in a uniform, and finally settles on an undershirt; he describes the awkwardness of his drawing — not with false modesty, but as a statement of fact — and explains that he tries to exaggerate this awkwardness in creating a certain disjunction between the figures in his paintings. By this time he has decided to introduce a third figure into the painting, a man hovering over the victim with a gun, who is seen mostly from behind. He goes back to his file to select a picture of the kind of pistol he wants and then dispatches a student to purchase a toy pistol that matches the picture; eventually he gets the student to serve as a model, holding the pistol in the appropriate gesture and position while he sketches him. He also solicits a critique on the size and position of his sketched figures from his wife, Nancy Spero.

Turning next to paint, Golub mixes colors and fills in certain details with a brush. Then, with the help of students, he pastes strips of paper around the outlines of the figures, switches to larger brushes and a roller, transfers the canvas to the floor, adds a solvent, and goes through an elaborate process of blotting, scraping (with a meat cleaver), and further sketching and painting, which continues after he moves the canvas back to the wall.

This abbreviated synopsis describes only a central part of the film’s mosaic; intercut with the above are TV clips and comments from gallery spectators, with Sivak’s music and various commentaries bridging these sequences. We learn from Golub that this painting “has something to do with what we’re involved with in El Salvador” (“I once described myself as a machine for producing monsters. But my production of monsters is really minuscule compared to the real production of monsters”).

There’s never any pretense that Golub’s activity is being filmed by an invisible camera — the presence of the filmmakers is constantly felt — and there’s no attempt to challenge or provoke the audience on the part of either Golub or the film. Both are concerned with directly engaging the spectator rather than with climbing on a soapbox. Golub’s remark that his art is “a report on how things are going today” is a statement of fact that we can interpret in a variety of ways, and part of the role of the TV clips and the comments from gallery spectators is to suggest some of this variety rather than impose a single reading.

The film is concerned with hidden depths as well as flat surfaces; part of the painting process that we see is involved with covering up previous work, turning the painting into a palimpsest, and Sivak’s variable and layered score, which mainly makes use of wind instruments and percussion, often seems to build its textures according to related principles. Some of the individual comments connect up with others: a girl in a gallery says of Golub’s paintings, “They make me feel very ugly”; and Golub himself remarks later, “Another ugly item goes out into the world.” Another viewer, at a show of Golub and Spero’s work in Northern Ireland, where the central painting is finally hung, compare’s Spero’s positive images of women with Golub’s negative images of men; and still another woman says while looking at a Golub canvas, “It doesn’t seem like there’s any space in there for women at all.”

Part of what makes the Kartemquin group’s approach to this subject distinctive is that it treats the exhibition of Golub’s painting as an essential part of the production process. There’s no magical moment when the painting is proclaimed to be “complete” that exists in isolation from its engagement with an audience. Indeed, when students are finally hammering in grommets to hold up the canvas and Golub is affixing his signature to the bottom, the filmmakers take care not to show us the finished work as a whole entity before it reemerges in a social context at its gallery opening; and even there, we never see it detached or isolated from its audience.

There are a couple of minor flaws in Golub; neither can be regarded as serious, but both seem to be worth noting. While the film certainly acknowledges the presence of Nancy Spero, it never seems entirely comfortable about how to deal with her as an artist distinct from her husband; the only facets of her work that are broached are those that relate to his, and her work is treated rather reductively as a consequence. The film also isn’t entirely confident about where to end; after a stunning match cut from wall graffiti in Northern Ireland to Golub walking past wall graffiti in New York, the film continues with a brief anticlimactic section in which Golub discusses a couple of his other paintings, and brings up the question of his capacity to depict blacks in one of them. The sequence is interesting enough in its own right, but it adds nothing indispensable to what has gone before.

Otherwise, Golub strikes me as being virtually perfect, both in achieving everything that it sets out to do and in the more general political program of conceptualizing its own agenda. Perhaps because this view of the painterly process is brought to us by filmmakers whose previous concerns have been with social issues, it conveys the exhilarating sense that art is inseparable from both the world that engenders it and the world that receives it.