From the July 14, 1989 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

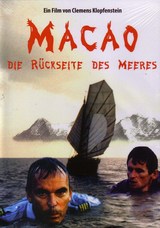

MACAO, OR BEYOND THE SEA

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Clemens Klopfenstein

Written by Klopfenstein, Wolfram Groddeck, and Felix Tissi

With Max Ruedlinger, Christine Lauterburg, Hans-Dieter Jendreyko, Shirley Wong, and Che Tin Hong.

1. Some part of me feels an enormous gratitude for movies that I don’t fully understand. The compulsive legibility of commercial movies — designed to be synopsized in three or four sentences, promoted in one or two catchphrases, represented in a short trailer, consumed in a single gulp — has a tendency over the long haul to give clarity a bad name; Hollywood’s form of lucidity usually rules out feelings, moods, and ideas that can’t be encapsulated so simply. People are fond of comparing movies to dreams, but when was the last time you had a dream that could be synopsized as effortlessly as a Hollywood movie?

Part of the allure of dreams is their mystery — not the kind of mystery that a Marlowe or a Freud could solve, which reduces the unknown to the status of a riddle, but the larger kind of mystery, whose uncanniness is a matter of aura and atmosphere, a cosmic question mark that can’t be resolved by plot contrivances or symbolic substitutions.

It’s similar to the difference between poetry and prose, and poetry is a rare and delicate commodity in commercial movies, particularly because it is so stubbornly resistant to paraphrase. Speaking broadly, poetry (like dreams) invents a language of its own in order to express itself, while most prose (like most movies) makes do with the everyday language that we already have. It’s hardly accidental that the great film poets — Murnau, Dovzhenko, Dreyer, Welles, Cocteau, Bresson, Tati, Tarkovsky (to name only a few) — seldom turn out to be as “commercial” as the filmmakers who are closer to the more workaday rhythms and subjects of prose.

2. One of the many alluring things to me about Macao, or Beyond the Sea was that I knew next to nothing about it before I saw it. Considering its special qualities, it can’t be accidental that it comes to us not through any commercial distributor, but with a traveling package of half a dozen international films selected by Wendy Lidell and collectively called “The Cutting Edge” — the second such program that she has put together. (The first “Cutting Edge” program, which turned up at the Film Center almost two years ago, included such masterpieces as Tian Zhuangzhuang’s The Horse Thief, Raul Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream, and Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A Time to Live and a Time to Die.)

At a time when U.S. distribution of foreign-language films has shrunk to a paltry fraction of what it used to be, making this country a backwater and last stop for many of the most important and challenging features that are currently being made, Lidell has come up with one of the few solutions around for beating the system. By booking her current cycle into about 30 “nontheatrical” sites across the country — museums, universities, film clubs, and so on — she is giving her intriguing batch of films a much wider circulation than any of them could possibly have gotten in an ordinary commercial run (which, given the conservative practices of most distributors, would mean only limited engagements in a handful of major cities).

Usually, a rave review from Vincent Canby in the New York Times is the only way a foreign-language film can reach a wider public — creating a ridiculous bottleneck that needlessly cripples distribution of “smaller” films in the U.S. The reason for such a monopoly isn’t Canby’s strength as an individual critic, but the institutional power of the Times in legislating upscale middlebrow taste, which is perceived in the business as the entire foreign-language-film market. (As Samuel Fuller once pointed out to me, if Vincent Canby lost his job at the Times and repaired directly to a bar, it’s highly unlikely that anyone in the bar would give two cents for his opinion.)

The superiority of Lidell’s method can be easily tested. Her second “Cutting Edge” series opened at the Film Center last weekend with Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Dust in the Wind and Yuri Illyenko’s The Eve of Ivan Kupalo, continues this weekend with Macao and Derek Jarman’s remarkable The Last of England, and concludes next weekend with Jose Alvaro Morais’s The Jester and Anne-Marie Miéville’s My Favorite Story. With the sole exception of the Miéville film — a work of some interest that is nonetheless not up to the level of the other five — each one of these films is indisputably more exciting, interesting, and original than any new foreign-language film currently being distributed in Chicago.

3. I can try to give an idea of what Macao, or Beyond the Sea is about, but be forewarned that it can’t be called an objective description. Synopsizing a film like Macao is tantamount to offering an interpretation of it, and there’s no good reason for my interpretation of Macao to get in the way of yours.

A couple named Mark and Alice (Max Ruedlinger and Christine Lauterburg) who appear to be very much in love are walking through the woods to a cottage; there they interview an elderly couple about the correct local words for certain rock and plant formations in the mountains of this remote Swiss area, which is called Oberland. Shortly afterward, while making love, Mark playfully identifies some of Alice’s body parts with the words they’ve recently learned.

At an airport in Zurich they’re still discussing the Oberland dialect as Mark prepares to leave for Stockholm, a trip that’s clearly connected to his work in philology. After he departs, Alice drives home, singing a strange, lyrical yodeling song.

Next we see Mark swimming fully dressed in the ocean, apparently the survivor of a plane crash. He grabs hold of a suitcase floating nearby, and makes his way to shore; there he is assisted by a Chinese man who leads him to a nearby village. On the way they pass another Chinese man who is heading for the shore to help another apparent survivor who we later learn is Krueger, the plane’s pilot.

At a hotel in the village a Chinese woman gives Mark fresh clothes, and a little girl brings him a cup of tea. Wanting to find a telephone, he tries to speak to the local people in English, but they speak only Chinese and he resorts to pantomime. They direct him to a nearby post office, where he places a call to Alice in Zurich; we cut to Alice in Zurich, and see that her phone is not ringing. Mark goes back to the hotel, pantomimes his plane crash to the amusement of some locals, is brought another cup of tea by the little girl, and returns to the post office to try to phone Alice a second time, again without success. Then, when he tries to send a telegram, he notices on the post-office form that he’s in Macao.

Eventually, Mark meets up with Krueger and they try to figure out a rational explanation for where they are. (Mark initially surmises that they’re on an island full of Mongolian refugees.) They board a ferry that supposedly leads away from Macao, but when they reach their destination they find that they’re at the same dock that they’ve just left. Interspersed with all this are shots of Alice dressed in a traditional peasant outfit and performing her yodeling song to a crowd of local peasants on a rocky hillside. Back in Zurich, she learns from a TV news broadcast that Mark’s plane crashed in the Baltic Sea, and shortly afterward, a man from the travel agency that booked the flight turns up at her door.

This is only the first part of the story, but it conveys most of the basic premises. Eventually Mark and Krueger conclude that they’re dead and that Macao is some version of paradise. Alice and the agent wind up at a body of water, where she sings a wordless, yodeling lament. Mark and Krueger decide that their only hope is to return to the ocean and start swimming (“I’ve never heard of anyone dying in paradise”); after they begin, a group of Chinese men set off in a boat in search of them — which parallels the search party that is looking for survivors in the Baltic.

By now, I’ve given you almost two-thirds of the plot, and I’ve hardly told you anything.

4. All of the night scenes in Macao are filmed in black and white through a blue filter, beginning with our initial glimpses of Alice and Mark making love and proceeding through scenes of Mark and Krueger in Macao and Alice and the travel agent in Zurich. Creating a separate poetic register that corresponds to “another world” even before Mark boards his plane for Stockholm, this device recalls the use of blue gels in projecting silent films to suggest night, and reminds us that the silent cinema embodied certain poetic attitudes as a matter of course — attitudes that are much less common in contemporary sound films. (The pantomimes of Mark for the Chinese locals and the unsubtitled Chinese that we hear in Macao may recall certain aspects of the same silent-film tradition and its lack of reliance on language.)

5. When he reviewed Macao for the Village Voice earlier this year, J. Hoberman suggestively noted that “the faux naif Klopfenstein . . . uses semitropical China and rural Switzerland to stand in for heaven and earth, respectively.” In the Berner Zeitung last year, Peter Schranz observed that “the clever cyclic structure of the movie” has been compared to Escher paintings.

In a piece entitled “Thoughts . . . About Creating Macao” Klopfenstein says, among other things, that (a) the film was partially inspired by a 1980 photograph in the Italian publication L’Espresso showing “a completely relaxed human body in torn clothes” floating “on the metallic blue sea” after an Italian passenger plane crashed into the Mediterranean; (b) the cups of tea offered by the little girl to Mark in the film represent Greek mythology’s “cup of oblivion”; (c) the song Alice yodels was originally inspired by a Japanese folk melody heard in Kurosawa’s Ikiru, and is the first Swiss yodel ever scored in a minor key (orgeli, the musical instruments that accompany yodels, are customarily tuned for major keys); and (d) after scouting for locations all over Macao, Klopfenstein finally found exactly what he was looking for in a tiny, “timeless, shabby” fishing village on a nearby island called Coloane, which is where he shot most of the “Macao” sequences.

All of these observations carry some interest, but I tend to mistrust them as guides for understanding Macao because they limit rather than expand the movie’s resonance as dream material by superimposing dreams of their own, even if some of these dreams also happen to be factual. Hoberman’s “heaven and earth” idea can’t be totally dismissed, but it introduces a religious dimension to a fantasy that strikes me as being wholly secular. Similarly, the Escher comparison and the notations of Klopfenstein imply that possessing outside information brings one closer to the movie’s concerns, and I’m not at all confident that it does.

The sheer weirdness of Alice’s yodeling in the film may strike some viewers as camp. But camp, after all, implies an essential knowingness on the part of an audience — what might even be regarded as a surfeit of knowledge — which in this case implies that (a) yodeling is corny by definition, (b) we know that yodeling is corny by definition, ergo (c) Alice’s yodels have to be campy. Maybe they are, but I found them evocative and beautiful, and the film, in its self-generating and self-defining context, wouldn’t be nearly as lovely and as enticing without them. (By and large, the film’s sound track is as pleasurable as its images.)

6. There’s another movie called Macao, a Hollywood effort produced by Howard Hughes and released in 1952, starring Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell. According to standard auteurist parlance, it’s the penultimate film of Josef von Sternberg — before he gave up Hollywood entirely to make his personal and poetic testament, The Saga of Anatahan, on which he functioned as writer, director, cinematographer, and narrator.

Actually, Hughes and so many others mucked about with Macao (including Nicholas Ray, who was brought in to reshoot some scenes) that it hardly belongs to Sternberg at all. Sternberg himself acknowledges as much in his autobiography, where he devotes only four terse sentences to the film: “After Jet Pilot [another Hughes production] I made one more film in accordance with the contract I had foolishly accepted. This was made under the supervision of six different men in charge. It was called Macao, and instead of fingers in that pie, half a dozen clowns immersed various parts of their anatomy in it. Their names do not appear in the list of credits.”

It’s very easy to synopsize Hughes’s Macao — it has none of the poetry of Sternberg’s best work and none of the dreamlike conviction of Klopfenstein’s film (which was shot, incidentally, by Klopfenstein himself). Klopfenstein’s Macao may not be the masterpiece that Sternberg’s Anatahan is, although one thing is certain: it is no less the product of a single poetic, romantic, and idiosyncratic mind, an imaginary world with its own laws and nuances — including its own peculiar notions of life and death. And it is an equally lush treat for the senses.