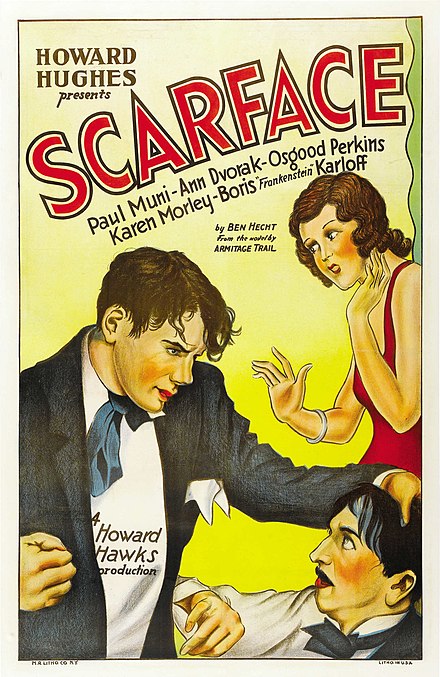

What distinguishes the criminal indictment of Trump in Georgia from his three preceding indictments is its finally forcing the media to call the man a gangster via its repeated use of the term “racketeering”. This brings us, at long last, to the basic ground level of understanding and acknowledging held by Americans in the 1920s who had the clear sight and honesty to call Al Capone a crook, meanwhile implicitly or explicitly dubbing him the king of Chicago. But why has it taken our media this long to call a former President a crook? It seems that more Americans today believe in him as their public servant than 20s Americans thought the same about the mobsters in their midst, although I might be wrong about making this assumption. Either way, the 20s crowd was way ahead of us in acknowledging their own living conditions. And in appreciating them: Capone cared about culture (e.g. opera) whereas the Donald can only succeed if or when he makes us meaner and uglier.

Read more

From The Soho News (February 18, 1981). — J.R.

Ici et Ailleurs

A film by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville

Against the Grain

A film by Tim Burns

Radical Images

James Agee Room, Bleecker Street Cinema

Despite all the signs of exacerbated brilliance in Godard’s work since 1968, it is arguable that only after he left Paris in 1973 for Grenoble and Rolle — and before he made Every Man for Himself about a year ago — has he been able to function seriously as a political filmmaker, in direct and personal confrontation with his subjects.

Before that, preoccupations with the “correct” lines about certain struggles and their representations have cheifly yielded case studies for conservative armchair Marxists — ideal meditations for Parisian camp followers preferring to keep their feet dry and their politics fashionably academic. And from the vantage point of the next five years, it is difficult to avoid seeing Godard’s recent alliance with Coppola, at least partially, as a gesture of impotence and defeat.

The more purposeful stretch of his career that I have in mind begins with Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), in 1974, continues with Numéro Deux (1975), Comment ça va and Sur et sous la communication (both 1976) and ends with his difficulties in getting his second TV series France/tour/détour/deux/enfants broadcast as he intended in 1978 and 1979. Read more

A special sort of Christmas essay from the Chicago Reader (December 23, 1994). — J.R.

Over the past year we’ve been hearing a lot about the theme of redemption in current movies. Actually the seeds of this trend were probably sown back in 1980, when Raging Bull came out, but now “redemption” is becoming something of a buzzword. I recall being taken slightly aback when I heard Harvey Keitel, speaking at the 1992 Toronto film festival, employ the term without any trace of irony in regard to Reservoir Dogs. And since then I’ve been hearing it more and more, mainly in relation to movies associated with Quentin Tarantino (not only Reservoir Dogs but also True Romance, Natural Born Killers, Killing Zoe, and Pulp Fiction) and such varied films as Cape Fear, Cliffhanger, Forrest Gump, The Professional, and even Heavenly Creatures.

What’s surprising is not only the odd assortment of movies in this new canon but those that are automatically excluded. Looking over last year’s releases, one might logically conclude that movies dealing with the spiritual redemption of their lead characters would include, say, Schindler’s List, Little Buddha, Savage Nights, The Shawshank Redemption, Bill Forsyth’s grossly neglected Being Human, and Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Blue, White, and Red. Read more

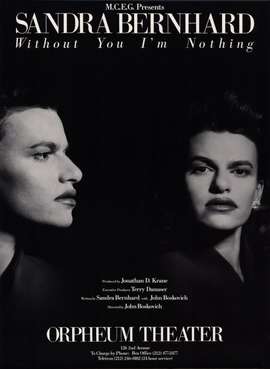

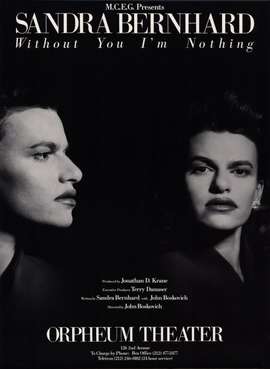

From the Chicago Reader (July 6, 1990). — J.R.

WITHOUT YOU I’M NOTHING

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Boskovich

Written by Sandra Bernhard and Boskovich

With Sandra Bernhard, John Doe, Steve Antin, Lu Leonard, Ken Foree, and Cynthia Bailey.

Once upon a time, before postmodernism came along, art tended to be about reality and the world — not always, to be sure, but more often than today. Then a group of professors and hucksters (as well as huckster-professors) got together and said, “What are reality and the world except particular versions of what we used to call art? And anyway what do we know about the world apart from what we see on TV, which is a form of popular art? The subject of art has always been other art, and postmodernism — unlike modernism, which is old hat by now, and all art prior to modernism, which is even older hat — is up-to-date art about other art. And what’s up-to-date is what sells.” Or words to that effect.

If capitalism is devoted in part to developing new markets, and advertising and journalism are devoted to promoting them, then postmodernist criticism is a means of backing up that promotion with hard intellectual currency. Read more