From the Chicago Reader (July 21, 2006). — J.R.

Made at Fox on the heels of The Girl Can’t Help It, this inventive 1957 comedy by Frank Tashlin is his most avant-garde (surpassing even Son of Paleface) and probably his most political — and therefore one of his most misunderstood. Tashlin adapted a Broadway play by George Axelrod, discarding almost everything but the title, the advertising milieu, and actress Jayne Mansfield. Shot in glorious color and CinemaScope, the film stars Tony Randall as a Madison Avenue executive who recruits Mansfield to endorse his product, and it presents a thoughtful and multifaceted polemic against the success ethic (a key line: “Success will fit you like a shroud”). Like Chaplin’s A King in New York, released the same year, the movie delivers a devastating caricature of 50s America; both directors, anticipating Jean-Luc Godard’s journalistic directive that one can — and must — place everything in a film, created dystopian versions of New York in which TV and advertising (rightly perceived as synonymous) obliterate the divisions between public and private. In keeping with George S. Kaufman’s maxim that “satire is what closes on Saturday night,” Rock Hunter flopped at the box office and was disastrous for Tashlin’s career. Read more

The following was written at some point in the early 1980s, as a kind of postscript or pendant to my first book, the autobiographical Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (New York: Harper & Row, 1980; 2nd ed., Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). I was living in Hoboken at the time, and secretly in love with another writer whose first name was Veronica. A slightly altered and doctored version of this piece eventually turned up in Ian Breakwell and Paul Hammond’s English anthology Seeing in the Dark: A Compendium of Cinemagoing (London: Serpant’s Tail, 1990). The version here has also been altered and doctored a little, and I’ve added all the photos, including those of the Ritz before and after its 1985 restoration. — J.R.

Putting Back the Ritz

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Between about 1947 and 1951, when the Ritz Theater in Sheffield, Alabama was still open (it was built in 1928 and received an Art Deco upgrade for talkies about five years later), my main encounters with the place, between the ages of four and eight, were on trips with my father across the river to pick up the final reports on the daily receipts on all four of the Rosenbaum theaters our family owned in Sheffield and Tuscumbia. Read more

This review for the March 1976 issue of Monthly Film Bulletin was part of a larger project, tied to my position as the magazine’s assistant editor, to have other films by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet that were distributed in the U.K. reviewed in the magazine — in that particular issue, History Lessons (by Yehuda E. Safran), as well as The Bridegroom, the Comedienne and the Pimp (by Tony Rayns) and Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg’s Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene (by Jill Forbes). That same issue of the magazine inaugurated a back-cover feature that persisted for the publication’s remaining life and years, devoted in this particular case to a detailed bibliography that I compiled of interviews, scripts, and “other statements and texts” by Straub and Huillet, in half a dozen different languages. —J.R.

Nicht Versöhnt oder Es hilft nur Gerwalt, wo Gerwalt herrscht (Not Reconciled, or Only Violence Helps Where Violence Rules)

West Germany, 1965

Director: Jean-Marie Straub

“Far from being a puzzle film (like Citizen Kane or Muriel), Not Reconciled is better described as a ‘lacunary film’, in the same sense that Littré defines a lacunary body: a whole composed of agglomerated crystals with intervals among them, like the interstitial spaces between the cells of an organism”. Read more

I’m grateful to have Kristin Thompson’s detailed and useful report on the Jacques Tati exhibition at the Cinémathèque Française, which closes on August 2nd and which I won’t be able to attend myself. But there’s one very small point in her account with which I disagree. I’m not referring to her spelling of Playtime as Play Time — a long-standing position of hers, based (I believe) on the styling of the film’s ads and opening title credit — because it’s possible that she’s been right about this while I and virtually everyone else have been wrong. (For me, the cinching argument either way would be how Tati spelled the title himself. I’m sorry that I never thought to ask him, during the brief period in 1973 when I worked for him.)

No, my disagreement has to do with the influence exerted by Tati on David Lynch, which Kristin deals with only parenthetically by noting that Lynch “might conceivably be said to reflect a Tatian influence only in The Straight Story.” I’m not disputing whether or not The Straight Story reflects Tati’s influence; as nearly as I can recall, this hadn’t occurred to me when I saw the film, and she might well be correct. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 29, 1990). A more recent look at this sequel shows that it dates badly, even (and perhaps especially) with all its Trump references. Its gibes all remain on the same level, even when they’re funny, so that it never becomes disturbing (as its predecessor does) or provocative. — J.R.

GREMLINS 2: THE NEW BATCH

***

Directed by Joe Dante

Written by Charlie Haas

With Zach Galligan, Phoebe Cates, John Glover, Robert Prosky, Robert Picardo, Christopher Lee, Haviland Morris, Keye Luke, and Dick Miller.

A cautionary tale set in a Frank Capra universe, Joe Dante’s original Gremlins (1984) gives us a kindhearted, unsuccessful inventor named Peltzer (Hoyt Axton) who buys a furry little creature called Mogwai as a Christmas present for his teenage son Billy (Zach Galligan). He finds Mogwai in Chinatown, in a curio shop run by the sage Mr. Wing (Keye Luke), who doesn’t want to sell it, but Wing’s practical-minded grandson, who says they need the money, arranges the deal anyway. Peltzer is warned to follow three rules of animal maintenance: keep Mogwai out of the light, don’t get it wet, and, above all, never feed it after midnight. After Peltzer brings it home, he names the pet Gizmo, reflecting his own taste in crackpot inventions. Read more

Since I’m no longer a regular reviewer and never have been much of a fan of the Coen brothers’ special brand of scornful, smart-ass caricature, I’ve been slow in catching up with A Serious Man, which turns out to be one of their most interesting (not to mention most serious, or at least most “serious”) movies. Even though they’ll never come nearly as close to Franz Kafka as Kubrick does in the costume-shop sequences of Eyes Wide Shut, there’s something about their taste for surrealist nightmare that flourishes here when it’s tied to a sense of Jewish misery and doom; and even though their sense of period here is as post-modernist-faulty as it’s ever been, and some of their weirder forays are plainly misfires (e.g., the precredits sequence), their personal take on what it meant to be Jewish in Minneapolis in the 60s still carries a certain charge.

As for their penchant for stylistic pastiche, what’s most striking to me about the behavioral freakishness and geekiness on display here is the degree to which they seem to derive in this case from a non-Jewish model — specifically, David Lynch’s very WASPy Eraserhead. (If memory serves, the only other time that the Coens went in for Jewish stereotypes was in Barton Fink, and then their principal stylistic guides, Polanski and Kubrick, were both Jewish and specifically Eastern European in their gallows humor.) Read more

From the July 14, 1989 Chicago Reader. –J.R.

MACAO, OR BEYOND THE SEA

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Clemens Klopfenstein

Written by Klopfenstein, Wolfram Groddeck, and Felix Tissi

With Max Ruedlinger, Christine Lauterburg, Hans-Dieter Jendreyko, Shirley Wong, and Che Tin Hong.

1. Some part of me feels an enormous gratitude for movies that I don’t fully understand. The compulsive legibility of commercial movies — designed to be synopsized in three or four sentences, promoted in one or two catchphrases, represented in a short trailer, consumed in a single gulp — has a tendency over the long haul to give clarity a bad name; Hollywood’s form of lucidity usually rules out feelings, moods, and ideas that can’t be encapsulated so simply. People are fond of comparing movies to dreams, but when was the last time you had a dream that could be synopsized as effortlessly as a Hollywood movie?

Part of the allure of dreams is their mystery — not the kind of mystery that a Marlowe or a Freud could solve, which reduces the unknown to the status of a riddle, but the larger kind of mystery, whose uncanniness is a matter of aura and atmosphere, a cosmic question mark that can’t be resolved by plot contrivances or symbolic substitutions. Read more

Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S., a catalogue/collection put together to accompany a film series at the Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

SHERLOCK JR. (1924)

In Buster Keaton’s masterpiece, which he directed

solo, he plays a lovesick movie projectionist who

climbs into the movie screen to solve a crime, walking

through several different kinds of movies and

landscapes in the process. Not simply a charming

dreamlike fantasy, this is also a lovely piece of

Americana circa 1924.

TWO TARS (1928)

A better-than-average Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy

short about two sailors (or «two tars,» according to

the slang expression) on leave and their dates culminates

in an epic grudge match occurring in the midst

of an endless traffic jam, making this extravaganza

the ideal companion-piece to 1941. Supervised by

Leo McCarey and filmed by none other than

George Stevens, this was directed by Laurel and

Hardy regular James Parrott.

THE MUSIC BOX (1932)

Perhaps the greatest of Stan Laurel and Oliver

Hardy’s sound shorts (1932), which won them

an Academy Award, is a half-hour epic of sorts,

most of it devoted to their torturous efforts to deliver

a piano to a hilltop home. Read more

This appeared originally in the July 23, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

Eyes Wide Shut

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Written by Kubrick and Frederic Raphael

With Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, Sydney Pollack, Marie Richardson, Madison Eginton, Todd Field, Julienne Davis, Vinessa Shaw, Rade Sherbedgia, Leelee Sobieski, and Abigail Good.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Writing about Eyes Wide Shut in Time, Richard Schickel had this to say about its source, Arthur Schnitzler’s 1926 Traumnovelle: “Like a lot of the novels on which good movies are based, it is an entertaining, erotically charged fiction of the second rank, in need of the vivifying physicalization of the screen and the kind of narrative focus a good director can bring to imperfect but provocative life — especially when he has been thinking about it as long as Kubrick had” — i.e., at least since 1968, when he asked his wife to read it. This more or less matches the opinion of Frederic Raphael, Kubrick’s credited cowriter, as expressed in his recent memoir, Eyes Wide Open. But I would argue that Traumnovelle is a masterpiece worthy of resting alongside Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” Kafka’s The Trial, and Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl. Read more

This is the first review I ever did for Monthly Film Bulletin, around the same time that I started working for the magazine (at the British Film Institute, then on 81 Dean Street) as assistant editor, in late summer 1974; this ran in their September issue. –J.R.

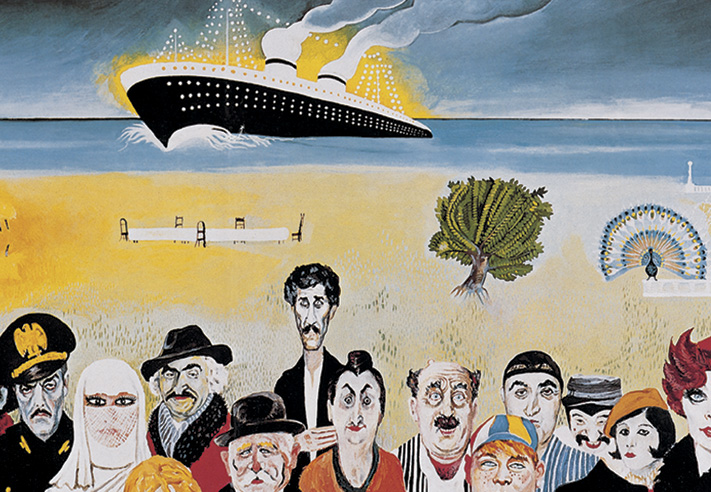

Amarcord

Italy/France, 1973 Director: Federico Fellini

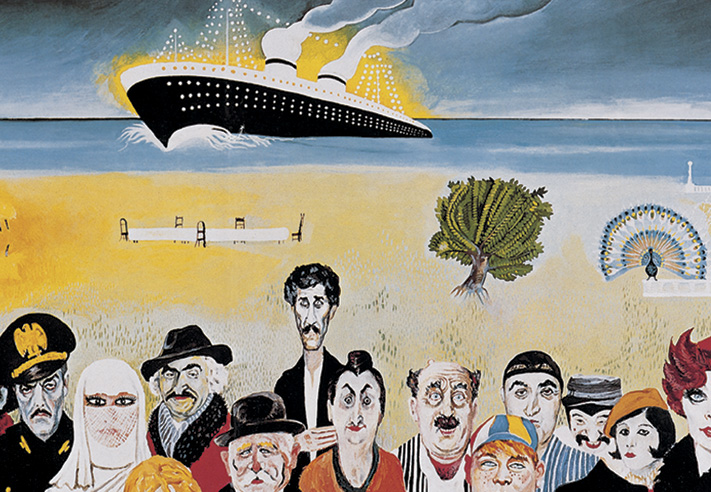

A small Italian town, during the Fascist period. The end of winter is announced by the arrival of manine, a white fluffy substance that blows into the province. That night, a large bonfire is built in the city square to celebrate the beginning of spring; a local resident recounts some of the town’s history. Volpina, the village whore, walks along the beach and flirts with construction workers, including Aurelio Biondi. At a stormy family dinner, Aurelio screams at his teenage son Titta for not working, and Titta is later sent b y his mother, Miranda, to the priest for confession. Asked whether he masturbates, he recalls and imagines several encounters with women in the town. A fascist rally is held to greet a visiting dignitary. That night, the police shoot down a gramophone from a church tower when they hear it playing a “subversive” song; prevented by Miranda from attending the rally, Aurelio is brutally interrogated by the police. Read more

This review of Jacques Rivette’s weirdest film, from the Winter 1976/77 issue of Sight and Sound, is one of the few pieces of my significant writing on Rivette from this period that hasn’t already been reproduced either on the excellent web site devoted to Rivette, “Order of the Exile,” or on this web site (e.g., my essay for Film Comment about Duelle). Having spent five very memorable days during the summer of 1974 watching the shooting of Noroît, in and around a 12th century fortress on the Brittany coast (see “Les Filles du Feu: Rivette x 4″, an article I wrote with Gilbert Adair and the late Michael Graham, reproduced on “Order of the Exile”), this was a film that I found in some ways even more compelling as a project than as a realized work.—J.R.

Noroît

If each new Rivette film marks a decisive break as much as a discernible development, Part III in the projected Scènes de la Vie Parallèle — the second film made in the tetralogy — reinforces this principle with a vengeance. Receiving its world premiere at the London [Film] Festival, immediately after a screening of Duelle (Part II of the cycle, discussed in my Edinburgh article elsewhere in this issue), Noroît has already occasioned the sort of extreme realignments provoked by Spectre after L’amour fou, or by Duelle after Céline et julie vont en bateau. Read more

I still seem to be in a minority in preferring Family Plot to Alfred Hitchcock’s other late films, but after reseeing the film countless times, I’m not about to revise my opinion. It would appear that some of Hitchcock’s biggest champions, such as Robin Wood, have tended to dismiss the film because it isn’t sicker. I tried to respond to their criticism at least provisionally in the opening of this review, written for the summer 1976 Sight and Sound, which they ran as their cover story for that issue and which I’ve revised, but only minimally. — J.R.

Family Plot

“Everything’s perverted in a different way,” Hitchcock has noted; and perhaps no other filmmaker has illustrated this postulate better, by starting from precisely the opposite premise. Without a well-established sense of the normal, the abnormal doesn’t even stand a chance of being recognized, and the director has always made it his business to offer all the right signposts and comforts to guarantee complacency before proceeding to unhinge it. Yet one of the rules of the game is deception, and if the Master’s artistry has been identified more with rude shocks than with the subtler conditioning which makes them possible, one can be certain that this too plays a role in his overall strategies. Read more

This appeared in the February 24, 1989 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

THE ‘BURBS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Joe Dante

Written by Dana Olsen

With Tom Hanks, Bruce Dern, Carrie Fisher, Rick Ducommun, Corey Feldman, Wendy Schaal, Henry Gibson, Brother Theodore, and Courtney Gains.

Director Joe Dante is the perfect refutation of the idea that popular American comedies have to be simple. His movies are never pretentious or difficult to follow, but embedded in each of them are a sophisticated understanding of popular culture and an awareness of the multiple stances and positions that are possible within the confines of supposedly simple genre movies.

Gremlins offered an ambiguous cluster of proliferating beasties to illustrate a cautionary moral fable about magic; it also managed to be an amoral satire of the same facets of the American dream exalted in the fable. Innerspace postulated the injection of a miniaturized Navy test pilot (Dennis Quaid) into the body of a hypochondriac (Martin Short), leading to simultaneous and parallel narratives as each character’s progress influenced the other’s.

A knowledgeable connoisseur of the American cartoon, Dante makes movies that take place in the kind of manic world where anything can happen. This sensibility bore particular fruit in his segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie (set in a universe ruled by the mind of a vindictive little boy who loved cartoons) and the climactic sequence of his Explorers (a nightmarish Mixmaster version of American TV strained through the sensibility, body, and technology of an extraterrestrial mimic); both of these segments anticipated the subversive universe that other filmmakers developed on Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Read more

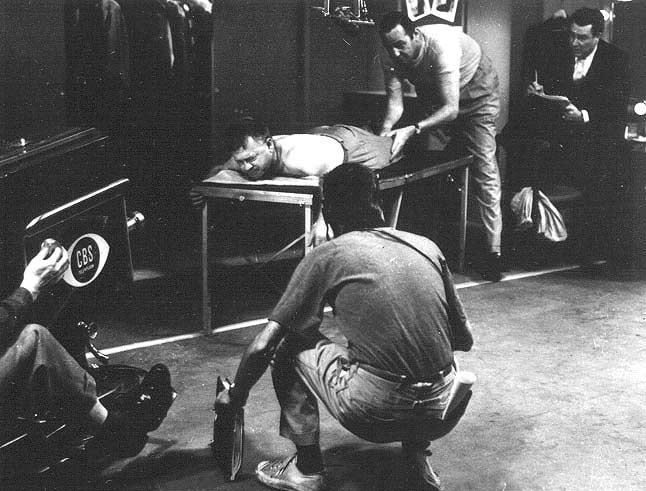

During my early teens, I watched Studio One fairly often, but Playhouse 90 went on too late for me to be able to watch it more than occasionally. So about two weeks prior to my 14th birthday, I missed The Comedian (1957), which I’ve just seen for the first time on a DVD compilation called The Golden Age of TV Drama — starring Michael Rooney in the title role as an abrasive, tyrannical TV star, Mel Tormé as his weak-willed brother, Kim Hunter as the latter’s despairing wife, and Edmond O’Brien as the comedian’s harried scriptwriter, and powerfully directed by John Frankenheimer. (I initially thought that was Frankenheimer on the left in the publicity photo below, but a friend suggests that it’s more likely Edmond O’Brien.)

Frankenheimer was probably the only TV director in that period whom I recognized by name, and it was a name that I valued highly. (He shot his first film feature the same year, and by the time The Manchurian Candidate came out five years later, his auteurist stamp was already unmistakable—especially in his volatile way of doubling one’s view of the action via TV monitors, already apparent at the very beginning of The Comedian.) Read more

If this Chicago Reader review from November 15, 1996 is of any interest today, I suspect this is more because of what it has to say about Australia and the U.S. than because of what has to say about a rather forgettable Bill Murray comedy. —J.R.

Larger Than Life

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Howard Franklin

Written by Roy Blount Jr., Pen Densham, and Garry Williams

With Bill Murray, Janeane Garofalo, Matthew McConaughey, Keith David, Pat Hingle, Jeremy Piven, Lois Smith, Anita Gillette, and Linda Fiorentino.

They say an elephant never forgets, but what they don’t say is, you’ll never forget an elephant. — Bill Murray in Larger Than Life

Farmer has bought an elephant at an auction. Gives him to Tom, Huck and Jim and they go about the country on him making no end of trouble. — from Mark Twain’s working notes for The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Are you still suffering from postelection malaise? I’ve just gotten back from a couple of weeks in Australia, where voting is compulsory, and for all the complaints I heard about the downsizing of government services and ugly efforts to renege on aboriginal land rights and change immigration policies, the political atmosphere seemed decidedly less alienated and despairing than it does here. Read more