This is my text, read aloud for an audiovisual essay on Arrow Films’ new digital release of Red Angel.Due to a technical glitch in my sound recording, Arrow had to omit the last portion of my narration, which is retained here, — J.R.

Hello. My name is Jonathan Rosenbaum and I’m a Chicago-based film critic. Thanks to a research project that I embarked on in the late 1990s, and which I was able to pursue in both the United States and in Japan, I estimate that I’ve been able to see around 40 of Yasuzo Masumura’s 55 features. These 55 features were all made between 1957 and 1982. And on the basis of the 40 or so that I’ve seen, I would offer the generalization that Masumura’s best features often tend to be the ones in black and white and Cinemascope that were made in the 1960s, which was his most prolific period, and that a good many of them star the wonderful young actress Ayako Wakao, whom he first encountered when he was working as an assistant director to Kenji Mizoguchi on the latter’s final feature, Street of Shame, only two years before Masumura directed her in his own second feature, The Blue Sky Maiden.

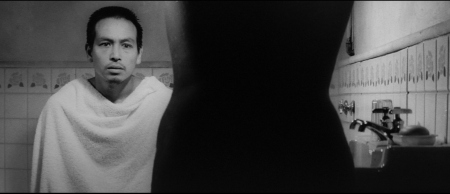

The Masumura film that sparked much of my interest and inspired my research project was Red Angel, which meets all three of these specifications: black and white, Cinemascope (or rather, the Japanese counterpart of that format), and Ayako Wakao. One of the things that intrigued me the most about it was how much it reminded me of the American B-film director Samuel Fuller—not so much the war films that Fuller actually made as the theoretical realistic ones he once described to me in an interview. When he was depicting the Normandy invasion in The Big Red One, he said, “I could have had that whole beach the way it was in life, all filled with nothing but intestines. That’s over 900 yards of just guts. Don’t know who they belong to! Bodies, too — a head here, an arm there, an asshole here, it’s all over the place. But I’m driving everyone out of the theater!” Red Angel, I hasten to add, doesn’t do any of those things, but it uses our imaginations to show that it might have, and it does force us to confront the reality of severed limbs and amputations. In fact, Masumura shows his mastery through an economy of suggestive details, and allows his sense of morality to emerge through acts that his mise en scene and his storytelling refuse to judge.

I wouldn’t call Red Angel Masumura’s very best feature—that would probably be A Wife Confesses, a 1961 courtroom melodrama that unfortunately hasn’t yet been made commercially available with English subtitles, maybe because it lacks the sexual exploitation elements thatmany Western viewers tend to associate with Masumura (including both color films such as The Blind Beast and Hanzo the Razor that I don’t much care for as well as ones that I find far more interesting such as Manji, Sex Test, and Love for an Idiot). I should stress that like many other prolific company or studio directors, Masumura took whatever was handed to him as an assignment, and his output was highly uneven: many good films, but also many duds. To my mind, Red Angel is almost a great film, marred only by a somewhat sentimentalized final chapter to the story.

Masumura was a film critic as well as a director–an intellectual who wrote a dissertation about Soren Kierkegaard as well as someone who studied filmmaking with Michelangelo Antonioni in Italy (who later returned the compliment late in his life by attending a Masumura retrospective while confined to a wheelchair). And as a film critic, he could be quite lucid about his own work. According to the Asian film scholar Earl Jackson Jr., Masumura designed his war films to undermine or subvert the three kinds of war films that were deemed acceptable at the time: antiwar films that addressed viewers’ consciences, comedies, and spectacles. In Yakuza Soldier (1964), for instance, a World War 2 comedy which precedes Red Angel, all the slapping and bone-crushing shown is by Japanese soldiers against other Japanese soldiers and none of it involves the Manchrians they’re fighting against; also, desertion is treated as a sane and responsible response to a soldier’s life. Nakano Spy School, made the same year asRed Angel, resembles Masumura’s industrial espionage pictures, such as Black Test Car, a film I’ve discussed on another Arrow release. In Nakano Spy School, everyone winds up betraying everyone else because the system itself is intrinsically rotten. The narrator-hero graduates from officer training school during the China-Japan war of 1937, tells his fiancée to wait a couple of years until his discharge, and then he never sees her again until he learns that she’s spying for the British and receives orders to kill her. Needless to say, they make love first—a seeming requirement in this grim subgenre.

Earl Jackson has pointed out that the fictional story of Red Angel is derived from two “historically verifiable situations that arose by 1939 in the Japanese campaign against China.” Lacking medical resources, “amputations became a default treatment for infection and injuries that often did not warrant such measures,” and presumably out of a fear of damaging morale, “amputees were often kept in [field hospitals] indefinitely without explanation.”

The most striking thing about Red Angel isn’t just the corruption of the system–guaranteeing that many wounded Japanese soldiers either died or got their limbs sawed off, often with little or no anaesthesia, and then not allowed to return home, which might have discouraged the civilian population from fighting. It’s also the sort of extreme behavior this provokes in the title heroine, both as a nurse and as a sexual angel of mercy and redemption. Masumura liked to depict extreme and even crazy kinds of behavior in his heroes and heroines as responses to the regimentation and conformity of Japanese society, and in this adaptation of a contemporary novel, which I haven’t read, a young nurse named Sakura Nishi agrees to have sex with her morphine-addicted boss if he gives a blood transfusion to a man who previously raped her—not exactly because she’s forgiven her rapist but because she doesn’t want him to die thinking that she was causing his death to get even. Later on, she gives sexual favors to an armless soldier in order to try to make his life more bearable, and then discovers instead that it makes his subsequent life more unbearable, leading to his suicide. I think that Masumura asks us to suspend any moral judgments about either her favors or his suicide and to regard these acts analytically as bizarre responses to wartime conditions–conditions that he does encourage us to judge.

The first time I saw Red Angel, I was reminded of MASH, the movie that made Robert Altman famous, a comedy about funloving American army surgeons during the Korean war. But I now think that the mixture of sex and surgery in MASH is quite unlike what Masumura does with this mixture in Red Angel. Both filmmakers oppose wartime bureaucracy. But the message ultimately being sold in MASH is how healthy a mob’s collective euphoria can be, especially when led by partying surgeons and waged against sexual hypocrites and religious fanatics, whereas Masumura is more concerned with ethical scruples about collective sentiments and policies. As his interest in Kierkegaard suggests, Masumura was a bit of an existentialist who thought about individual responsibility in relation to a society that was so collectivized that the Japanese language doesn’t even distinguish between singular and plural nouns. This is undoubtedly part of what makes him so fascinating as well as eccentric to us in the West–