From The Soho News (June 4, 1980). In the interests of full disclosure, I should note that Jackie Raynal was and is one of my dearest friends. — J.R.

Deux Fois

A Film by Jackie Raynal

Bleecker Street Cinema, June 9

Debt Begins at Twenty

A Film by Stephanie Beroes

Millennium, May 24

Recalling my four successive visits to the Cannes Film Festival in the early ’70s — when the daily glut of movies and accompanying hardsell was already enough to turn a hardened film freak into a deflated beachball — I still harbor fond memories of the kind of movies that used to spend my days looking for, and the ones that would savor for days more, days on end, once I found them. They were movies that allowed me and Cannes to slow down and linger a bit and regain our strength, and afforded us that pleasure by refusing to hype us into or out of anything that denied either of us the solipsistic joy of total self-absorption.

By taking their own sweet time (all the time in the world) to explore their own bittersweet fantasies, and allowing us to follow them only if we insisted, these movies were like little self-contained oases conjured up and plunked down improbably in the midst of camel stampedes, which is probably why so many of my colleagues hated them — and why most of you, in turn, have heard of so few of them, if any at all. (Pedro Portabella’s Vampyr, James B. Harris’s Some Call It Loving, Werner Schroeter’s The Death of Maria Malibran and Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Who Is Beta? are four characteristically lush and obscure examples that spring to mind.)

As luck would have it, I never had the pleasure of discovering Jackie Raynal’s Deux Fois (Two Times) in those circumstances, even though it was made by a Frenchwoman around the same period — a professional film editor on a visit to Barcelona and environs in 1969. (Today, Raynal is a New York filmmaker and a programmer at the Bleecker Street Cinema, whose Monday Independent Cinema series coincidentally included The Death of Maria Malibran when it started back in April, and concludes with a double bill of Deux Fois and Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx, on June 9.)

But if I’d seen Deux Fois at Cannes back then, I’m sure it would have gotten me over a few lumps. And even though this is years later, when Francophobla seems to be raging, and hippies are prone to be regarded as less appealing than (say) the German measles — when, in short, the specter of a goofy French avant-garde hippie film of that period isn’t likely to sound very fashionable –- it just might get you over a few lumps, too,if you give it half a chance.

***

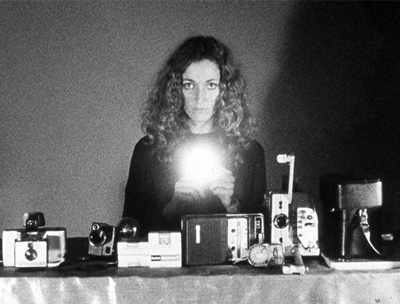

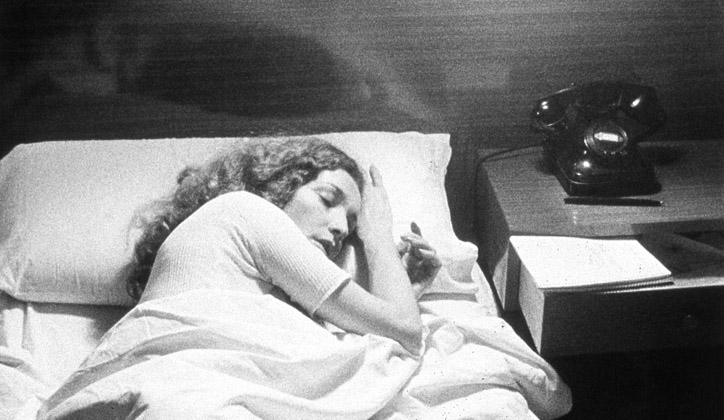

Deux Fois was made in 35mm and black and white, features Raynal in practically every sequence, and has no plot of any sort. Instead of a story it gives you a flow of sequential events that formally rhyme with each other in a variety of ways, so that the title is a succinct representation of the method involved (although there are certain things that the film gives us three, four or five times, too, always with distinct variations). Consequently, on one level the movie is a kind of elementary editing puzzle that asks, “How did I get from this long-take sequence to this one that follows it?” and/or “What are the sexy forms of duplicity between these two sequences — their secret points of agreement and accord, as well as their strongest points of tension?” It’s a film, in other words, about a couple, and about coupling — there is a man who appears with Raynal in many of the sequences — as well as repetition.

Perhaps because Raynal made Deux Fois after a long stint of editing commercial French narrative films (including several early works by Eric Rohmer). there is a liberating feel to it that, all proportions guarded, may have something to do with those obscure oases that I used to cherish at Cannes — a sense of ease regained, of identity tasted and slowly chewed. Raynal’s self-absorption, which occasionally suggests a flipped-out, female version of Jacques Tati’s Hulot character — luxuriates in the space that it affords itself like a puppy in clover, and whether you feel like stepping inside it or not obviously has a lot to do with your own temperament.

“All the images of our imaginations are real,” Raynal declares in an early autonomous sequence. At their best, the sequences of Deux Fois are like neatly sculpted, delicately lit arenas where different versions of this postulate can be staged, by Raynal and spectators alike. Solipsistic, masturbatory games, to be sure. But isn’t the camera a solipsistic instrument, and moviegoing largely a solipsistic activity — regardless of their manifold alibis and social excuses (which is what most film criticism is all about)? Deux Fois is perhaps an avant-garde film first of all because it allows itself no shame whatsoever for reveling in the pleasures to be found in those simple facts.

***

Whether Deux Fois should be regarded as a feminist film – as was implied by the detailed coverage given it in the first issue of Camera Obscura (“A Journal of Feminism and Film Theory”) in 1976 -– is a different matter, and one questioned by Raynal herself in a recent interview (to be published in a double issue of Millennium Film Joumal. due out this fall). In a similar spirit. Stephanie Beroes decided to omit Recital, a 1978 short she described as feminist, from her program of recent work at Millennium last Saturday, because, she said, it didn’t seem to fit the context of the other two films she was showing.

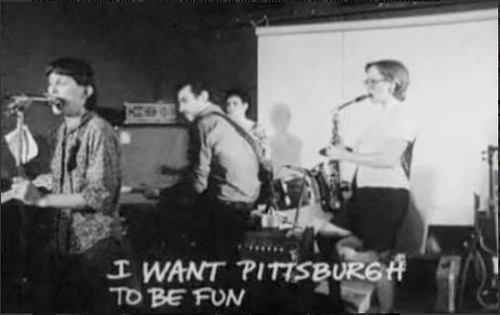

Not that Valley Fever and Debt Begins at Twenty, the films in question, have very much in common –- apart from a graceful craft evident in everything from the hand-held camerawork to the jump cuts and other kinds of transitions. The former movie, a 20-minute short completed early last year, is a conceptual work about perception that takes off from a text by phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty beginning, “There is a perceptual uneasiness in the state of being conscious.” Debt Begins at Twenty, which is twice as long, is a “docudrama” about Bill Bored, the drummer in a New Wave band known as the Cardboards, shot entirely in Pittsburgh.

Beroes, who is 27, has divided much of her recent time between Pittsburgh and San Francisco, pointed out at the screening that one of the differences between the punk scenes in both cities is that the one to be found in Pittsburgh is basically working class, while the one in San Francisco seems to be made up largely of middle-class art students. Certainly a lot of the charm of Debt Begins at Twenty has something directly to do with its youthful cast, which consists mainly of the members of three New Wave groups -– the Cardboards, the Dykes, and the Shakes (the latter now known as Combo Tactics) – who provide one another with serious and enthusiastic audiences.

***

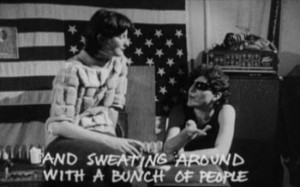

Starting and ending with a Dick Tracy comic strip about punk, the film faithfully follows the movements of Bored in trying unsuccessfully to sell his used record albums, watching TV, reading a comic, talking on the phone and singing “Low Level Radiation” with his band. The images are helpfully outfitted with handwritten subtitles that either duplicate or supplement what’s heard; one that appears over the performance just cited is, “Warning: There is no footage of A-bombs in this picture.”

All three of the bands involved recall some of the spastic/elastic/plastic conceits of a James Chance (or a Brad Dourif, offering a punk performance as the lead hayseed in John Huston’s Wise Blood) without quite the same degree of anger/angularity/anguish. As a modest celebration of music growing like a hothouse flower out of the grayness of Pittsburgh, the movie reminded me in spots of A Hard Day’s Night, Having a Wild Weekend, and even some of the Sam Katzman exploitation specials featuring Bill Haley and Chubby Checker. Different musicians are asked the same questions (e.g., “How would you like to die?”), and we get stirring renditions of such homegrown classics as “I’m Bored,” “Hysterectomy” and “You Need a New Outfit”. (The latter leads off with the intriguing refrain, “Pretend your mind is a dress –- change it.”)

It’s entirely in the nature of the movie’s celebratory punk spirit that it points to (and snickers at) some of its own supposed technical flaws. An “AKG mike” is indicated, Dick-Tracy-like, with an arrow in one subtitle over a shot that allegedly shows us Bored sitting alone; and when Sesame Spinelli, a vocalist with the Dykes, looks the hero up in the final sequence (preceded by the title, “Six Months Earlier”) and winds up making love with him to a joyfully gyrating camera, the self-conscious acting and banal, embarrassed dialogue between them is happily lingered over. Reminiscent at times of some of the early romps of Warren Sonbert involving silent footage of frolicking friends and rock music, Debt Begins at Twenty provides as much honest fun as a day on the beach.