From the Chicago Reader (March 8, 1996). — J.R.

The White Balloon

Directed by Jafar Panahi

Written by Abbas Kiarostami, Panahi, and Parviz Shahbazi

With Aida Mohammadkhani, Mohsen Kalifi, Fereshteh Sadr Orfani, Anna Bourkowska, Aliasghar Samadi, Mohammad Shahani, and Mohammad Bahktiari.

In Iran the first day of spring is New Year’s Day, the celebration of which starts at a different time of day every year, and among the objects used in the celebration is a goldfish, which symbolizes life. The plot of Jafar Panahi’s extraordinary first feature, The White Balloon (opening this week at the Music Box), involves the adventures of Razieh (Aida Mohammadkhani), a seven-year-old girl who has her heart set on buying a new goldfish for the celebration, insisting that the ones her family already has are “too skinny.”

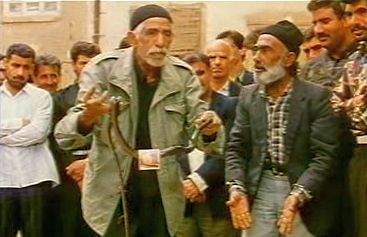

Only 85 minutes long, the film unfolds in real time and almost exclusively in exteriors along a few blocks of Tehran the morning of the New Year. The film opens in a market, where Razieh’s mother (Fereshteh Sadr Orfani) is shopping; she collects Razieh, who’s carrying a blue balloon, and they walk home together. Nearly all of the film’s other major characters — and even a couple of minor ones — are fleetingly glimpsed during this prelude, though we don’t recognize any of them yet. On their way home mother and daughter pass an alley where a crowd of men has gathered around a couple of male snake charmers, and Razieh’s mother pulls her daughter away with a brief reprimand that it isn’t good for little girls to watch such things.

Back in the family’s courtyard Razieh frets about her mother’s unwillingness to let her buy a new goldfish, but refuses to accept this decision as definitive. Her older brother Ali (Mohsen Kalifi) has returned from a shopping errand for their father, an unseen figure who angrily complains that he asked Ali to buy shampoo, not soap, then throws the soap at him. After Ali comes back again with the shampoo Razieh enlists his help in changing her mother’s mind about the goldfish, bribing him with her blue balloon. Insisting that she can buy the desired goldfish in the market for 100 tomans (“You’re crazy,” Ali tells her, noting that he can see two movies for the same amount), Razieh finally gets her wish. Her mother hands her a 500-toman banknote and asks her to bring back the change, and Razieh goes off with an empty glass jar to the fish store at the market a few blocks away.

En route to the store, however, she manages to lose the banknote twice, and the remainder of the movie, about 70 minutes, is devoted to her efforts to get it back again. If this sounds slight in terms of plot, it must be added that the film as a whole can be seen as both light and heavy — fun and easy to take as well as engrossing — though seeing it exclusively as light entertainment does it an injustice. For one thing, the immense importance of the banknote and the fish to Razieh is never shied away from, and part of the movie’s achievement is getting us to share enough of her viewpoint and emotions to make these things seem important to us. For another thing — and this is complexly tied up with the preceding project — The White Balloon reinvents time and our moment-to-moment perception of it, an accomplishment that’s anything but slight. To say that Panahi has served up the universe in a teacup makes the film sound overblown and pretentious, and it’s anything but. Yet it certainly is a universe — a densely realized space-time continuum suggesting both a picaresque novel and a piece of music — that taught me a lot more about the flow of time in everyday life than anything I’ve seen lately from Hollywood.

One of my most vivid childhood memories is of watching a bird building a nest, piece by piece, on a ledge outside a room where I was staying in my grandparents’ house. Part of what makes this memory so vivid is how completely it transformed my sense of time passing: duration became a matter not of how long I was sitting by the window but of how long it took a bird to construct a nest — which made everything else that happened in the vicinity during the same period relatively unimportant, a series of distractions.

In a similar fashion The White Balloon gets us to share Razieh’s sense of time passing, which entails not so much minutes ticking by — a separate flow that she and we become periodically aware of through radio announcements of the countdown to the New Year, which create a feeling of suspense — as what has to happen before she can retrieve the banknote, first from the snake charmers and then from a gutter behind the grating of a shop that’s closed for the New Year. What we experience, in other words, is the difference between subjective and objective time, which also becomes the difference between clock time and film time. (Given a film this beautifully realized, I doubt that knowing the plot in advance can do much harm, but readers who prefer not to know more should step off here.)

For film theorist André Bazin, the integrity of documentary film pioneer Robert Flaherty in Nanook of the North lay in his refusal to cut from Nanook hunting a seal to the seal that eventually emerges from a hole. “It is inconceivable,” wrote Bazin, that this scene “should not show us hunter, hole, and seal all in the same shot….It is simply a question of respect for the spatial unity of an event at the moment [it occurs] when to split it up would change it from something real to something imaginary.”

Leaving aside the fact that The White Balloon is a fiction film and hence imaginary, it’s entirely understandable that Panahi cuts from Razieh looking down the gutter at the banknote to a shot of the banknote itself. Why? Because the integrity here lies in the unity of an emotional event — Razieh looking at something, followed by what she sees — and not the unity of a spatial event.

The fanaticism and purity of Razieh’s desire — which lead her to recover the banknote twice — are charted over a limited stretch of time and space, yet Panahi brings a sense of satisfying fullness to every moment in which that desire plays itself out. It can even accommodate other desires that conflict with her ostensible desire to purchase a particular fish — when it leads her to defy her mother’s instructions by penetrating the world of men represented by the snake charmers, to linger in front of a pastry shop, and to ignore her parents’ admonition not to talk to strangers by conversing with a soldier on leave (Mohammad Shahani). And far from being an idealized desire, it also leads her to snub a new friend and virtual savior when she achieves her ostensible desire–recovers the banknote and pays for the fish — and wants to rejoin her family. Following the extent and multifaceted consequences of that desire wherever they lead is Panahi’s elected project.

Critics who describe this movie as fluff or as conventional realism — and a surprising number do, even some of the film’s more enthusiastic partisans — have to ignore a good deal of what happens to arrive at such conclusions. They have to overlook such peculiarities as the sound editing, which periodically foregrounds the radio reports about how much time remains before the New Year — reports that, unless I missed something, are never accompanied by any visible radio. They have to repress Panahi’s formal decision to shoot all the action in the streets and alleys of a small patch of Tehran, apart from the airy interiors of a couple of shops — which places domestic interiors out of bounds (comparable to the ground rules of Jacques Rivette’s 1980 Le pont du nord, though its exclusive use of exteriors was “justified” by the claustrophobia of the central character, who’s just emerged from a long stint in prison) — and some of the strange consequences of that decision: for instance, we never see Razieh and Ali’s father, even though we hear him. These critics also have to overlook the highly unconventional swerve in the film’s narrative trajectory that ultimately leaves us not with Razieh or Ali, who run off to join their parents, but with an Afghan balloon seller (Aliasghar Samadi), who becomes an important character only in the film’s final act.

The White Balloon could be described without exaggeration as the most popular non-American movie that showed at the Cannes film festival last May, where it wound up receiving the Camera d’Or. If you’re wondering why it’s taken so long to open here, why it’s being handled by a small distributor (October Films, which also handled Terence Davies’s Distant Voices, Still Lives) rather than a big one, and why it hasn’t been nominated for an Oscar, I suspect a single explanation suffices: because it’s Iranian.

Iranian films carry special burdens in the West. When Iranian film professionals voted to make The White Balloon Iran’s official entry for Academy Award consideration, the Iranian government, as a way of protesting economic sanctions against it, asked the academy to withdraw the film from consideration. The academy refused, though the film didn’t make it into the (mainly mediocre) selection of five foreign film nominees. Yet the enormous prestige The White Balloon has brought Iranian cinema has already created a backlash among Iranian critics, which also seems related to the international reputation of Abbas Kiarostami — Panahi’s mentor, and the film’s principal screenwriter.

Neither especially religious nor especially political in his public life, Kiarostami is regarded by some Iranian critics as a darling of French intellectuals (and French camp followers), a trendy internationalist whose cultural calling cards tend to be Western; some of these critics, for instance, have complained about the prominent use of Vivaldi and a French car in And Life Goes On… Of course any Iranian filmmaker who achieves some international prominence — and therefore at least some theoretical independence from Iran in terms of funding — is bound to be viewed with suspicion by the government, though this suspicion is clearly offset by some protection from harassment as well. (The more Islamic and more uneven — though undeniably gifted — Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Kiarostami’s most distinguished counterpart in Iranian cinema, benefits from the same protection, even though some of his films have been banned.)

Born in 1960, Panahi made three documentaries and two short films for Iranian television between 1988 and 1992, the last a tribute to Kiarostami’s first film, the ten-minute Bread and Alley (1970). Having seen Bread and Alley at Locarno last August, I can report that its relation to The White Balloon is immediately apparent — in the canny blending of documentary and fiction and in the skillful use of the labyrinthine alleys of Tehran as an integral part of the mise en scène.

Kiarostami founded the film unit at the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults — a state-supported organization started in the late 60s by the shah’s wife that’s now known as the Kanun — and it has produced practically all of his films to date. Not all of these films are, strictly speaking, children’s films, and some are documentaries; but most of them feature children, and in many respects they establish a particular kind of filmmaking that The White Balloon exemplifies: loosely scripted narratives with documentary elements that employ mainly nonprofessional actors. One technique developed by Kiarostami that Panahi adopts is keeping the overall story a secret from the actors — especially the child actors — to ensure the spontaneity of their performances.

After attending screenings at the institute during his childhood and finding himself drawn to Kiarostami’s work, Panahi eventually decided he wanted to work for him; following the example of Luis Buñuel, who got his start in filmmaking by working for Jean Epstein, he phoned his master, went to the shooting site of Through the Olive Trees, and eventually was hired as assistant director. During the shooting of that feature, Panahi told Kiarostami the basic plot he had in mind for The White Balloon, and Kiarostami helped him out by dictating an impromptu screenplay into a tape recorder during car trips to and from shooting locations, then revising the transcribed results. (Kiarostami used the same method in scripting his next film, which is expected to surface at Cannes in a couple of months.)

The White Balloon — perhaps the first serious Iranian picture to receive serious distribution in this country (and hopefully not the last) — is clearly the work of a Kiarostami disciple, but it adapts his overall approach in a highly personal manner. If Kiarostami’s most noticeable “signature” is the cosmic, extended long shot–a distant view of the characters and landscape that condenses the action and meaning philosophically, as in the stunning final shots of And Life Goes On… and Through the Olive Trees — The White Balloon works comparable wonders with a restricted time frame and physical terrain.

If there’s one school of thought that tends to dismiss The White Balloon because it’s Iranian, there’s another school of thought that tends to laud it for the same reason. People who assume that I belong more to the second group aren’t entirely wrong, but determining which school of thought any viewer subscribes to — and this includes Iranians as well as non-Iranians — is no simple matter.

Case in point: In what strikes me as a well-intentioned but wrongheaded and ungenerous review by Simon Louvish in the January 1996 Sight and Sound, The White Balloon is assigned to “a genre which might be called low-intensity third-world neo-realism,” in which “children, being pre-political, are an obvious subject in a country where art is tightly controlled by the government and subject to the strictures of an Islamic State” — yielding a film where, “as in Cold War Soviet cinema, filmmakers take refuge in a broadly based humanism, which highlights the daily solidarity of ordinary people while being able to comment obliquely on persistent social problems.”

My quarrel with this kind of analysis — which goes on to criticize The White Balloon for not even attempting to challenge, even cautiously, “the ubiquitous imagery of chador-clad women, fulfilling their traditional roles” — is that it places an outsize requirement on filmmakers like Panahi that most Western critics would never dream of placing on Western filmmakers. Though I share Louvish’s indignation about the enslavement of Iranian women, obliging every Iranian filmmaker to address this subject implies another (albeit less direct) form of enslavement — and one that costs the Western critic nothing.

Looking around at some of the apparent dividends of Western “adult” freedom that are also showing in Chicago this week — such as the sentimental sexist slop of Up Close & Personal, or the bold decision of Peter Greenaway in The Baby of Macon to dramatize the rape of a virgin (Julia Ormond) by 217 soldiers in 17th-century France, carried out with the church’s full blessing and plenty of Ormond’s ear-piercing screams — I wonder if the “broadly based” antihumanism of these films and countless others is supposed to serve as a model for the socially conscious cinema that Iranian filmmakers are supposed to aspire to, even at the cost of their careers. Admittedly, this week’s crop of films also includes the politically audacious The Birdcage, in which Elaine May’s hilarious script implies that only a drag queen could live up to Pat Buchanan’s dream of the ideal woman. But this movie is a rare exception in the politically gutless commercial cinema of the West that Louvish is implicitly castigating Panahi for not attempting to emulate.

Ultimately Louvish’s brief on behalf of Iranian women entails a trashing of The White Balloon because it’s Iranian. (Similarly, we demonstrate our devotion to the freedom of the Iraqi populace through anti-Saddam sanctions, but blame the massive deaths of Iraqi children through malnutrition that the sanctions entail on Iraq’s own Islamic strictures.) Even more subtly, the praise for Iranian cinema offered by some of my other colleagues — who argue that the multiple restrictions placed on Iranian filmmakers by their government parallel the “benefits” of the production code in classic Hollywood by offering filmmakers a tight system to work within (or against) — becomes another form of patronizing jabberwocky. These two Western critical alternatives seem to offer either the conservative assumption that Iranians are nothing like us or the liberal assumption that they’re exactly like us — neither of which happens to be true.

Speaking for myself, I can only report that some of the Iranian characters in The White Balloon — in particular an irascible tailor (Mohammad Bahktiari) quarreling with a customer — remind me of some urban American Jews, and some of the symbolism in the celebration of the Iranian New Year makes me think of the Jewish holiday Passover. Strictly speaking, these responses are “critical” only insofar as they counter the tribalism of both Jews and Iranian Muslims by recognizing that both tribes initially came from the same part of the world. In other respects, however, these responses aren’t critical at all; they’re merely descriptions of the trajectories of my own imagination as it’s engaged by the film. But how good or bad this movie is has nothing to do with how Iranian it is. Panahi’s consummate artistry, I’m happy to say, lies elsewhere.