From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1976). -– J.R.

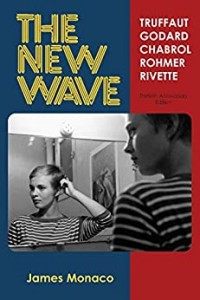

THE NEW WAVE

By James Monaco

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS, £9.95.

A writer whose methods immediately evoke the mood and dynamics of an energetic classroom, James Monaco restricts The New Wave to the five film-making alumni of Cahiers du Cinéma most often identified with that label: Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer and Rivette. Considering the dearth of books in English on the subject (only Peter Graham’s anthology and Raymond Durgnat’s early monograph — both long out of print, and the latter unmentioned in the present book — qualify as predecessors), it is a fertile field for any critic interested in organizing a lot of diverse material, and this task is handled by Monaco with grace and assurance; for its bibliography alone, this over-priced volume is well worth having. Beginning with an evocation of Rivette’s first encounters with Godard and Truffaut (and later Chabrol and Rohmer) at the Avenue de Messine Cinémathèque in 1949 or 1950, he proceeds to the films of each until, some 320 pages later, he has burrowed his way through over a hundred features and shorts.

Lots of grist for the mill; but what kind of product is the Monaco factory manufacturing? Three-quarters of the text is given over to Truffaut and Godard, with the latter getting twice the space of the former, and each of the other three sharing roughly a tenth of the book apiece. The point of this arithmetic isn’t to question Monaco’s priorities but to identify them — although it may be that the unavailability in the U.S. of several films by Rohmer, Chabrol and Rivette at least partially dictated the proportions. Perhaps not coincidentally, Truffaut and Godard are also the figures Monaco appears to be most comfortable discussing; the first two sections bristle with confident assertions, while the others seem altogether more questioning and tentative.

On Truffaut, he writes with the ardor of a committed fan — passionately defending Domicile Conjugal, and even finding extended interest in Une Belle Fille Comme Moi — taking as his principal guideline two questions which he sees being posed again and again in the films: ‘Are films more important than life?’ and ‘Are women magic?’ On Godard, he is equally comprehensive but somewhat more guarded; by the time he reaches Pravda, serious political objections have cropped up, and near the end of this section he confesses that ‘There is something absolutely and inherently hollow about the abstraction of the intellect.’ But the predominant tone is much more upbeat, and he concludes that Godard’s art ‘leaves me breathless’.

Chabrol, treated as the most commercial of the group, a specialist in ‘films noirs in color’, is accorded a relatively terse summary, with abbreviated judgments occasionally taking the place of analyses (André Jocelyn is deemed ‘a nearly total disaster’ in Ophélia, with no explanation offered as to how or why); but the general claim that Chabrol is often taken more seriously by critics than by himself is agreeably substantiated by a witty quote from the director. Rohmer’s smaller oeuvre is approached somewhat more respectfully, with the director regarded as ‘very much a modern thinker, at least as compared with the Henry James of the turn of the century. Rohmer takes things much less seriously,’ and as someone who ‘has allied himself with contemporary film theorists like Straub, Fassbinder, Rossellini and. . . Godard, who have sought to extend the boundaries of the permissible in film language.’ Rivette, mainly seen in terms of his experiments with narrative — but with interesting passing comments on his use of rhythmical and musical structures — is regarded ambivalently as a more difficult and esoteric figure than any of the others.

Monaco oddly fails to consider any part of Rohmer and Rivette’s extensive careers as critics, which offer multiple clues about their film-making, while the more modest critical efforts of Chabrol are discussed at some length. More seriously, in his efforts to keep his study up-to-date with spanking new concepts and references, he can seem a bit hasty at times in his use of terminology. Words like ‘existential’, ‘structural’, ‘formalist’ and ‘materialist’ have acquired usages too specific to allow for broader applications without risking serious confusion, and to describe (say) Truffaut’s and Chabrol’s post-synchronized films as ‘materialist’ only makes sense if one ignores entirely the ‘materialist’ implications of the direct sound used by Godard and Rivette.

In terms of new material, an unpublished interview with Rivette furnishes the Introduction and last chapter with a number of helpful facts. Less satisfactory are the accounts of Rivette’s recent films, which abound in errors: at the end of Spectre, Bulle Ogier is said to be ‘still at the house’ rather than driving off to Paris, while the ’empty’ shots of Place d’Italie are wrongly described as being devoid of people; and the ‘inner plot’ of Céline et Julie is provided with a wholly imaginary resolution in which Camille is ‘seen’ smothering Madlyn while her rival Sophie is presumably absolved of all guilt.

But in the overall context of The New Wave, many of these objections can be written off as quibbles. The fact remains that such a volume is long overdue, and Monaco’s ease in marshaling his sources is well worth attending to. Above all, he conveys the distinct impression that despite all the similarities in taste and background that originally linked these five directors under a common banner, the distances separating them today are often much more striking.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM