From Sight and Sound (Spring 1985). — J.R.

With its continuing devotion to the independent and marginal, the Rotterdam Film Festival offered fewer peaks this year than last, but more than enough rolling happy valleys in between. Full-bodied retrospectives given to Jonathan Demme and Nelson Pereira dos Santos wove their way almost contrapuntally through the nine days of movies -– providing the selection with a sturdy populist backbone. Guided by the Langlois-like eclecticism and passion of director Hubert Bals, the festival virtually rebaptises every film that it shows under the banner of a relaxed, low-budget freedom that the Spielbergs and Coppolas can only dream about.

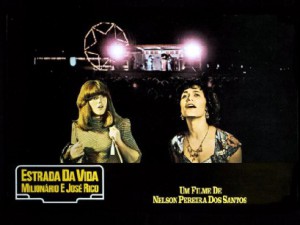

Pereira dos Santos and Demme are cases in point. From the sixteenth century (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman) to the post-nuclear future (Who Is Beta?) to the impoverished present (Rio, 40 Degrees; Vidas Secas), dos Santos’ films blend anthropological wit with neo-realist compassion. The sociological wit and Renoir-like warmth of Demme exude a comparable bias towards the downtrodden. Oddly enough, the two sensibilities nearly come together in the very different pop/folk musicals Estrada da Vida (1980) and Stop Making Sense (1984). Respectively a docu-drama about wall painters who make it big as country singers in Sao Paulo, and an on-stage concert performance by the Talking Heads, both films make striking use of flat colour backdrops to objectify and enhance the cultural clout of the performers. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1988). — J.R.

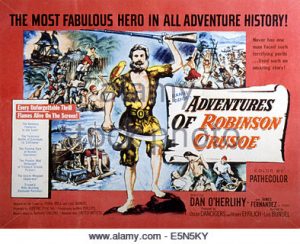

One of the most unjustly neglected of Luis Buñuel’s films, this 1952 feature also happens to be one of the two he directed in English (the other is the equally neglected The Young One). Buñuel shows an overall fidelity to the plot of Daniel Defoe’s classic novel while steering the thematic concerns in a somewhat different direction, and even manages to incorporate a few touches of surrealism. Dan O’Herlihy is superb in the title role (he was nominated for an Oscar when this film was belatedly released in the U.S.), while Jaime Fernandez makes a more than adequate Friday. The color photography is also distinctive. 90 min.

Read more

Read more

R.I.P. Nicolas Roeg, 1928-2018. From The Movie no. 85, 1981.— J.R.

It is surely more than just a coincidence that director Nicolas Roeg has used leading pop stars and rock personalities in three of his five features to date. The sheer satanic presences of Mick Jagger in Performance (1970), of David Bowie in The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976) and, to a lesser extent, Art Garfunkel in Bad Timing (1980), all have something slightly magical about them — as if they held the implicit promise that unusual and outsized events were going to take place around and, in large measure, because of them. Boldly delineated in each case like the demonic princes of dark impulses, they are offered as guides and portals into the decadent fantasies which these films often traffic in. As Roeg told critic Harlan Kennedy in an interview:

What I find interesting about singers is that they all have the qualities of performers but they’re untouched in terms of acting. They’re not from the New York school of this or that: they’re not from the London theatre….So many actors have lost their intent, their beginnings. They’re not this travelling group of players that one evening is a king, another evening is a beggar. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 6, 2001). This is also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema.— J.R.

The Day I Became a Woman

***

Directed by Marzieh Meshkini

Written by Mohsen Makhmalbaf

With Fatemeh Cheragh Akhtar, Hassan Nabehan, Shabnam Toloui, Cyrus Kahouri Nejad, Azizeh Seddighi, and Badr Irouni Nejad.

“Aren’t you afraid?” some of my stateside friends asked before I visited Iran for the first time last February. “Only of American bombs,” I replied. Notwithstanding all of the things that are currently illegal there — such as men and women shaking hands or riding in the same sections of buses — I’m not sure I’ve ever been anyplace where people display more social sophistication in terms of hospitality, everyday courtesy, or sheer enterprise in the use of charm and persistence to get what they want. Some of this character came through in Divorce Iranian Style, a fascinating documentary that turned up at the Film Center a couple of years ago showing the aggressive resourcefulness of Iranian women in divorce court, despite the repressive laws they have to work with.

The locals I spoke to tended to be pessimistic about the reformist movement — regarding Mohammad Khatami about as skeptically as American liberals regarded Bill Clinton during his last year in office — but it also quickly became clear that some aspects of Iranian life are not defined by Islamic fundamentalism and that what might seem hopeless in one context might be possible in another. Read more

A column for Caiman Cuadernos de Cine, submitted May 28, 2018. — J.R.

The commodification of film categories that publicists otherwise find difficult to market — especially “independent,” “restoration,” and “film noir”—often involves a certain amount of deception when it comes to existential identities.

“Independent” became a commercial category only after moguls maintained that the Sundance Festival was devoted to celebrating films without studio backing — even though “success” at Sundance meant a studio sale that typically entailed a loss of independence. “Restoration” is a label that absurdly gets slapped onto all sorts of real or alleged upgrades of older films, such as one with a newly mutilated and reconfigured soundtrack (the 1992 rerelease of Orson Welles’ Othello), a re-edit (the 1998 Touch of Evil), a belated first edit (the posthumous 2018 The Other Side of the Wind), and sometimes merely a new print. And “film noir” — a term whose meaning has already been slippery to begin with, applied retrospectively to a group of films said to share certain stylistic, formal, and thematic traits — now functions ahistorically and sometimes deceptively while increasing the market value of a given feature by obfuscating its politics.

On Criterion’s new Blu-ray of Frank Borzage’s Moonrise (1948), Peter Cowie’s interview with Hervé Dumont — whose book on the director should be shelved alongside Chris Fujiwara’s book for the same publisher (McFarland) on Jacques Tourneur — primed me perfectly for my second look at this masterpiece. Read more

From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983).

Although I still agree with most of my arguments here, it’s now clear to me that my characterization of Paul Schrader’s politics in 1983 were oversimplified at best, and simply wrong at worst. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. Read more

From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983). Due to the length of this, I’ll be posting it in four installments. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. Read more

From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983). Due to the length of this, I’ll be posting it in four installments. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. Read more

From Film: The Front Line 1983 (Denver, CO: Arden Press, 1983). Due to the length of this, I’ll be posting it in four installments. — J.R.

Tenants of the house,

Thoughts of a dry brain in a dry season.

T.S. Eliot, Gerontion

Preface: When I was approached last year about inaugurating a series of volumes surveying recent avant-garde film, I immediately started to wonder about how this could be done. Having lived nearly eight years in Paris and London and about as long in New York, I’ve had several opportunities to note the relative degree of information flow between these and other centers of avant-garde film activity, and the growing isolation of New York from these other centers made my own fixed vantage point less than ideal in some ways. When a colleague told me that Jonas Mekas had recently said that it was no longer possible to know what was happening in experimental film as a whole, a bell of recognition rang in my head, and I knew at once that Mekas was the only available oracle l could turn to. The Lithuanian patron saint of the American avant-garde film, now 60, has been an American filmmaker for at least half of his life, and a chronicler of the avant-garde film in New York — mainly in The Village Voice and (more briefly) Soho News — for at least 15 years. Read more

Commissioned and published by Fandor in September 2010. — J.R.

Teaching silent film in the mid-1980s at the University of California, Santa Barbara, I was astonished to discover I was the first teacher there who had ever shown a film by Louis Feuillade. Sadly, there was a good reason: at that time, only one Feuillade film was in distribution in the U.S. — Juve contre Fantômas (Juve vs. Fantômas) — and few if any of my teaching colleagues had ever seen it.

My own introduction to Feuillade, one of the most memorable filmgoing experiences in my life, was attending, on April 3, 1969, a 35-millimeter projection of all seven hours of his 1918 crime serial, Tih Minh, at the Museum of Modern Art -– along with Susan Sontag, Annette Michelson, and other enrapt friends and acquaintances. Part of the shock of that experience was discovering that even though Feuillade was a contemporary of D.W. Griffith — born two years earlier, in 1873 — he seemed to belong to a different century. While Griffith reeks of Victorian morality and nostalgia for the mid-19th century, Feuillade looks forward to the global paranoia, conspiratorial intrigues, and technological fantasies of the 20th century and beyond.

Read more

An article about “remakes” of independent documentaries, from the November 20, 1998 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Shulie

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Elisabeth Subrin

With Kim Soss, Larry Steger, Rick Marshall, Eigo Komei, E.W. Ross, Marion Mryczka, Ed Rankus, Kerry Ufelmann, and Jennifer Reeder.

What is it about American culture that compels the film industry to do remakes? The compulsion has been growing over the past two decades — one of my oldest friends, a cinephile and sometime screenwriter based in Hollywood, was already viewing it with philosophical resignation ten years ago. As she put it, “My best friends and I have been spending most of the 80s sitting in cars discussing remakes.”

Since the early 80s we’ve been inundated with more cultural objects than ever before, but we have less and less sense of what to do with them. It’s easy to explain the Hollywood remake syndrome as unimaginative cost accounting: it made money before, so why not do it again? Then there’s the expanding youth market, which encourages unimaginative cost accountants to figure that former hits can be recycled for younger generations — one of the justifications offered by Gus Van Sant for his forthcoming remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. Read more

This appeared originally in Film Comment, July-August 1978, and was reprinted by Saul Symonds in March 2005, with separate new prefaces by myself (reproduced below) and David Ehrenstein, in the online Light Sleeper (which is no longer up, alas). It’s also reprinted in my recent book Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues (2018). — J.R.

Obscure Objects of Desire: A Jam Session on Non-Narrative

By Raymond Durgnat, David Ehrenstein and Jonathan Rosenbaum

Preface by Jonathan Rosenbaum, March 2005:

When this piece was written, or more precisely assembled, over 30 years ago, Ray Durgnat and I were sharing a house in Del Mar, California with experimental filmmaker Louis Hock. Ray and Louis were teaching film in the Visual Arts Department at the University of California, San Diego, where I had taught the previous year — having been coaxed by Manny Farber into leaving my job as assistant editor of Monthly Film Bulletin and staff writer of Sight and Sound in London, at the British Film Institute, and returning to the U.S. after almost eight years of living in Europe. Ray, already a friend, also came over from London to take my position when I wasn’t rehired, and I was starting to work on a book that eventually became Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980). Read more

DARKNESS VISIBLE: A MEMOIR OF MADNESS by William Styron (New York: Vintage Books), 1990, 84 pp.

HAVANAS IN CAMELOT: PERSONAL ESSAYS by William Styron (New York: Random House), 2008, 162 pp.

Two late autobiographical books by a writer I’ve always liked —- the first somewhat disappointing, perhaps because I came to it with the wrong expectations, the second a pleasurable surprise.

I guess what I was hoping to encounter in DARKNESS VISIBLE, Styron’s brief and somewhat sketchy account of his own excruciating bouts with depression in the 1980s, was some clarification or extension of what I found so powerful about his treatment of bipolar behavior in SOPHIE’S CHOICE (1979) -– specifically the depiction of Nathan, which seemed to derive from some deep personal understanding of this condition. But Styron points out early on that his own malady was “unipolar,” not the same thing at all. Still, I admire the scrupulous way he avoids leaping to too many conclusions about a condition that he’s still far from fully understanding.

The late essays collected in HAVANAS IN CAMELOT deal with such topics as a few amicable encounters with John F. Kennedy (the title essay), an apparent contraction of syphilis during his youth (as a fledgling Marine at a naval hospital in South Carolina), his friendships with fellow novelists (Truman Capote, James Baldwin, and Terry Southern), some late prostate trouble, and walks with his dog in his early 80s. Read more

THE FURIES, directed by Anthony Mann (1950, 109 min.), in a Criterion box set.

Last night, I saw this grand, exciting, unruly failure, Mann’s first western, for the first time, thanks to the timely arrival of the DVD from Criterion, handsomely boxed with the Niven Busch novel that Charles Schnee (and Mann, uncredited) adapted it from. I haven’t yet sampled the Jim Kitses commentary, but there’s also an excellent new essay by Robin Wood that’s very attentive to both the strengths and weaknesses of the film, cross-referencing KING LEAR in all the right ways. And on the same disc, a Paul Mayersburg interview with Mann shortly before his death that was recorded for British television–the first I’ve ever seen–as well as a no less revealing interview with Mann’s daughter Nina, which introduces me to certain relevant aspects of Mann’s childhood: specifically, growing up mainly without parents in a Theosophical Institute in San Diego where there was an outdoor amphitheater that produced Greek tragedies, among other things.

My only complaint, really, is that there’s no allusion in the booklet to Arthur Hunnicutt’s uncredited appearance in the film––the same year he appeared as Chloroform Wiggins in Jacques Tourneur’s STARS IN MY CROWN. Read more

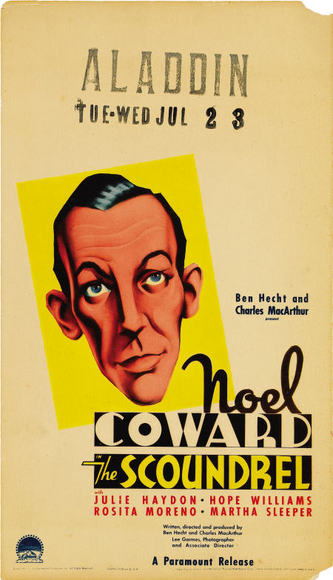

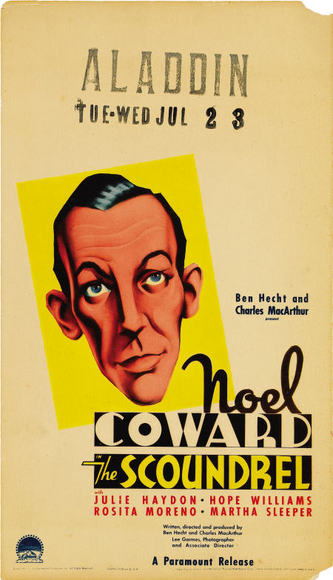

THE SCOUNDREL, written and directed by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, with Noel Coward (1935, 76 min.)

Interesting to discover from Alfred Kazin’s AN AMERICAN PROCESSION -– specifically, from the beginning of his chapter about AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY and THE SOUND AND THE FURY -– that Horace Liveright, the onetime publisher of Dreiser, was “the model for Ben Hecht’s maliciously engaging film THE SCOUNDREL“. Having recently reseen and again hugely enjoyed the second feature codirected as well as cowritten by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, starring Noel Coward in the title role as Anthony Mallare (apparently his first film part, unless one counts his uncredited cameo in Griffith’s 1918 HEARTS OF THE WORLD), I’d been wondering how much of this memorable antihero was attributable to the imaginations of the writer-directors and how much came from life.

Hecht directed or codirected seven features in all, starting with the equally mannerist CRIME WITHOUT PASSION (with its deliriously campy avant-garde prologue) in 1934 and concluding with the rather awful ACTORS AND SIN (codirected by Lee Garmes) in 1952. All of them are difficult to find nowadays, though I’ve managed to track down a few from various Mom and Pop operations on the Internet. Read more