From the January 30, 1998 Chicago Reader. Since I barely remember Kundun today, I’m pretty sure I must have overrated it, at least in relation to The Apostle (which I remember far better today, even in its truncated version). –J.R.

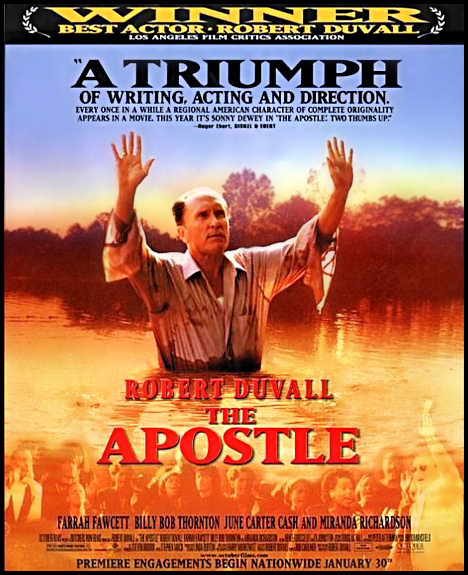

The Apostle

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by

Robert Duvall

With Duvall, Farrah Fawcett, Miranda Richardson, Todd Allen, John Beasley, June Carter Cash, Billy Joe Shaver, Walter Goggins, Rick Dial, and Billy Bob Thornton.

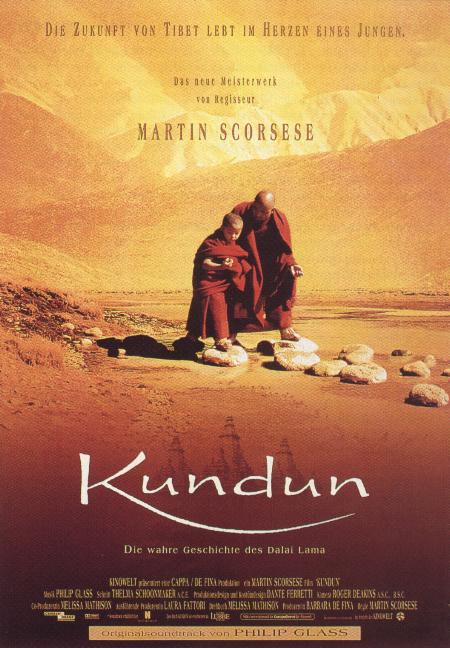

Kundun

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Melissa Mathison

With Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong, Gyurme Tethong, Tencho Gyalpo, Tsewang Migyur Khangsar, Geshi Yeshi Gyatso, and Robert Lin.

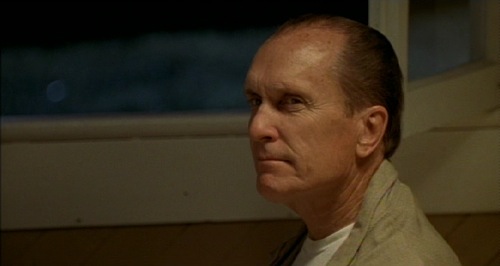

For all their obvious differences, both Kundun and The Apostle are spiritual but nonreligious movies about religious leaders, suffused with a perpetual sense of mystery and driven by an abiding curiosity that provokes our own curiosity as well. As a commercial property, each film amounts to an act of defiance, judging by their critical reception so far. Many mainstream critics have stepped out of Kundun asking, “What could Scorsese have been thinking of?,” and some have come out of The Apostle complaining that it’s basically an ego trip for its writer-director-star.

Both reactions perversely miss the point, telling us more about stereotypical commercial expectations in general than about either project in particular. To ask what Martin Scorsese might have been thinking when he made Kundun isn’t to ask a real question (obviously he was thinking about the 14th Dalai Lama) but to fret about why he wasn’t interested in making another star-studded commercial movie this time around. And contending that The Apostle is about Robert Duvall rather than something else — specifically, a Pentecostal preacher in Texas who critically assaults the young minister (Todd Allen) involved with his wife (Farrah Fawcett) and then hightails it to Louisiana, where he builds another congregation — is another way of dodging the issue, in this case by putting The Apostle on the same shelf with Eddie Murphy comedies and Madonna music videos. In both cases, I suspect, what’s really at issue is the seriousness and relative exoticism of what’s being investigated — which suggests that Scorsese and Duvall are more interested in posing questions than in delivering answers in the form of pseudostatements.

In recent interviews Duvall and Scorsese have each alluded to a documentary impulse in arriving at the respective styles of The Apostle (mainstream docudrama) and Kundun (introspective art film). The fact that both directors deftly mix professional, semiprofessional, and nonprofessional actors is part of this impulse (though many more of Kundun‘s actors are nonprofessionals); another part is their absorption in the material, which makes plot both a structure and a side effect but not the main focus. (Significantly, the heroes of both films are identified more often by their titles than by their names, which implies that their vocations precede and therefore determine their identities.) Duvall cites Englishman Ken Loach as his major influence — a fiction filmmaker, to be sure, but one who invariably works with documentary materials and methods (and, incidentally, a radical leftist whose politics are probably far removed from Duvall’s). And in the January-February issue of Film Comment, when Gavin Smith asks Scorsese, “Were you trying to do without familiar reference points, to take the viewer outside of the kind of realms they’ve encountered in cinema?,” Scorsese’s lucid declaration of principle seems equally applicable to Duvall’s approach:

“Exactly: to put a Western audience in the middle of a farmhouse in Amdo in the middle of nowhere in Tibet, and then in the middle of this palace, and not explain any of it. Not to condescend, but to throw you into the middle of a culture and let you sink or swim. If it’s alien, if you’ve never seen anything quite like it, you don’t even know what they’re doing or even what the ceremony is sometimes — whether it’s religious, political, or just eating breakfast — what do you get, how do you hook on to the people? There’s only one thing — you hook on to the people, which is what it should be.”

Substitute “integrated Pentecostal church service” for “farmhouse in Amdo,” replace “Tibet” with “Texas,” and you have a fair description of what much of The Apostle is like. Does this mean that some viewers, including critics, feel every bit as removed from Pentecostal fundamentalists as from Tibetan Buddhists? Judging from reactions I’ve heard, some feel more removed, even threatened — which is to say that they sink rather than swim, perhaps because they have more biases regarding fundamentalism. Indeed, The Apostle is exciting and important precisely because it invites us to consider a world that many of us, consciously or not, think is beneath consideration. And like Kundun, it offers this invitation without pretension, condescension, or false humility.

By refusing to buy into the Elmer Gantry stereotype, which suggests that every fundamentalist preacher who shows signs of being a scoundrel is also a hypocrite, Duvall’s movie throws us into a subculture of devout belief without the sort of moral signposts that many of us city slickers have grown to depend on defensively and as a matter of automatic reflex. Sonny, Duvall’s troubled and troubling preacher, may be a warped creature who lies to himself, but on the basis of everything we see and hear, he believes deeply in saving souls. And by making all the church services interracial, Duvall complicates our responses still further, especially if we stereotype most white fundamentalists as racists. (Or indulge in statistical guesswork, as Amy Taubin did in the Village Voice when she tried to prove that the film is racist. I would claim on the basis of my experience as an Alabama native with some background in the civil rights movement that these integrated services are believable; whether they’re typical is, of course, another matter.)

Though Duvall presents Sonny as a problematic hero, he never presents Sonny’s followers as a pack of idiots for believing in him. In fact, if The Apostle were the ego trip its detractors claim, its heart might be Sonny’s numerous sermons, but its true essence is the communal and spiritual exaltation that his preaching fuels and shares and rides on, in both Texas and Louisiana. The film asks us to experience that exaltation and decide where or if we belong in it, without making any simple judgments. The fact that Sonny is a dangerous character as well as a believer adds ambiguity to this process, but Duvall is less interested in validating or condemning him than in exploring him, as well as the world that he springs from and depends on.

It stands to reason, then, that Duvall’s principal cinematic building block, above all during the church gatherings, is neither the close-up nor the medium shot but the long shot. In the prerelease festival version, which was about 17 minutes longer, lengthy takes were equally important, increasing the spectator’s freedom in choosing how to come to terms with these collective events; the effect was that of an ethnographic documentary. For its commercial release, the film was re-edited by Walter Murch, apparently with Duvall’s cooperation (though Duvall stipulated that none of the services be shortened, even if they were edited differently); Murch’s major thrust was to chart a narrative path through this open-ended material, so that every cut now advances the story line.

Yet storytelling is what Duvall does least well, in this movie anyway. His genius for mise en scène emerges in individual sequences rather than the ways they fit together or produce a legible story. Though several characters resonate in both versions — not only Sonny but also Brother Blackwell (John Beasley), the retired Louisiana preacher whose former congregation he takes over; a radio station owner (Rick Dial); and the latter’s secretary (Miranda Richardson), whom Sonny tries to seduce — many loose plot strands remain. The new version minimizes this problem but reduces some of the original’s documentary-like immediacy and rawness, a clear case of style sacrificed to content. I’m still figuring out the full consequences of these changes, but even in its more streamlined version The Apostle is an awesome achievement.

Although The Apostle has its share of brief internal monologues — most of them added to the shorter version — these function mainly as narrative bridges and as indications of the preacher’s sincerity. The film’s focus is almost entirely on the external world, not the state of anyone’s soul except as it impinges on that world. In contrast, Kundun is mainly concerned with the subjective inner states of its title character, played at different ages by four actors, so that the occasional printed titles establishing dates and historical events function like thumbtacks, the structural equivalent of The Apostle‘s internal monologues. It begins with the recognition of the two-year-old Tenzin Gyatso as the 14th Dalai Lama in 1937 and ends with his departure and exile from Tibet in 1959, but our sense of period in his sheltered and remote world is fairly minimal.

A key framing device, taken directly from Melissa Mathison’s script, is a frontal shot of the Dalai Lama waking up, followed by a subjectively tilted, sideways view of his parents’ feet that rotates 90 degrees until they’re seen normally. We see this when he’s two years old and then shortly before he leaves Tibet, as a kind of waking dream that recalls the earlier experience. This passage from objective to subjective reality and back again, sometimes within the same shot, is a recurring pattern in the film; it often suggests a movement between reality and abstraction, particularly because dreams are accorded the same status as waking experiences.

The script grew out of some 15 interviews Mathison had with the Dalai Lama over several years, as well as his two autobiographies and several books about him. Scorsese’s treatment of this “found” factual material as the basis for abstraction oddly recalls the genesis of Raging Bull, which of all his films thematically resembles Kundun the least. (The earlier biopic is about a life dedicated to violence; this one’s about a life dedicated to nonviolence.) In the film’s most remarkable single shot, based on a nightmare recounted by the Dalai Lama to Mathison, the camera begins with him and then cranes up into the sky: he’s standing in the center of a field of corpses, all Buddhist monks clothed in red, and the field of red expands until the corpses lose their human identities, becoming simply an abstract visual pattern. More than one critic has improbably linked this shot to the crane away from the wounded soldiers in Gone With the Wind, which lacks precisely this sense of abstraction and vertiginous horror. (A likelier source and parallel, suggested to me by critic Kent Jones, is the camera pulling back from mounds of human hair in Alain Resnais’ short documentary about the Nazi death camps, Night and Fog, though the graphic and painterly effect also recalls certain details in Akira Kurosawa’s color films, especially Dreams.)

Much as The Apostle challenges many received ideas about fundamentalists (preachers and churchgoers alike), Kundun confounds the Hollywood boilerplate notion of a religious leader developing through a series of transcendental revelations. (A piece of 50s kitsch called A Man Called Peter represents the locus classicus of this formula.) Perhaps the closest thing in Kundun to a revelation of this sort is one of its loveliest details: the sight and sound of a rat lapping up water from a temple’s ceremonial cup during a moment of meditation. More characteristically, the film doesn’t even bother to define a particular point at which the spoiled brat of its early scenes, who demands to sit at the head of his family’s dinner table, is transformed into a holy man. Throughout the film cause and effect, the mainspring of most narratives, is replaced by a sense of spiritual synchronicity.

Indeed, many of the personal and historical events alluded to in the film occur offscreen, and most of those shown — such as the meeting between the adult Dalai Lama (Tenzin Thuthob Tsarong) and Chairman Mao (Robert Lin) — are deliberately soft-pedaled as homey incidents rather than trumpeted as earthshaking events. Sand paintings and mandalas are used symbolically to replace many other such events; by constructing an internal landscape with exquisite visual tact, Scorsese respects our curiosity about this individual’s life without contriving to satiate us with the usual travelogue and lecture material. In most cases such placebos limit our involvement, keeping us at a safe and comfortable distance from an exotic subject, but Scorsese’s more intimate approach invites us to respond instinctively.

I have one major demurral, however. Though I used to pride myself on being the first person to order Philip Glass’s debut recording in the early 70s (Music With Changing Parts), I’ve subsequently decided that the live experience of his music may be the only one worth having, apart from his score for Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach (see below). None of Glass’s scores has ever worked for me: they always seem to have been applied like varnish, and they tend to sound like reductive, congealed packages addressed to no one in particular. What felt like real and even swinging music in live performance comes across as new-age twittering in his sound tracks. His film score for Kundun may well be his best to date, but any spiritual lift I get from the film is in spite of Glass’s mechanical throbbing, not because of it.

A major reason for this lift is the human presence — people confronting us as other people and not as abstract concepts. This is precisely the quality that animates Glass’s music in concert and that his film scores fail to capture. Both Duvall and Scorsese argue that our proximity to other people counts for more than any shared beliefs, and whether you accept this notion or not, neither of these remarkable films would be possible without it.