This was originally a lecture given at a conference on Godard held in Cerisy, France on August 20, 1998. It subsequently appeared in a printed form somewhat closer to that found below, in Screen magazine (vol 40, no. 3), in Autumn 1999, as part of a Godard dossier assembled by the estimable Michael Witt. But, if memory serves, it took about a year of correspondence and wrangling before anyone on the magazine’s staff agreed to send me any copy of the issue. (Note: for a more general essay and interview with Godard about Histoire(s) du cinéma, go here.) —J.R.

Le Vrai Coupable: Two Kinds of Criticism in Godard’s Work

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Since the outset of his career, Godard has been interested in two kinds of criticism — film criticism and social criticism — and these two interests are apparent in practically everything he does and says as an artist. The first two critical texts that he published — in the second and third issues of Gazette du cinéma in 1950 — are entitled “Joseph Mankiewicz” and “Pour un cinéma politique”, and his first two features, A bout de souffle and Le petit soldat, made about a decade later, reflect the same dichotomy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 6, 1998). — J.R.

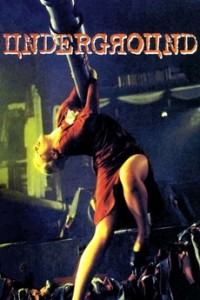

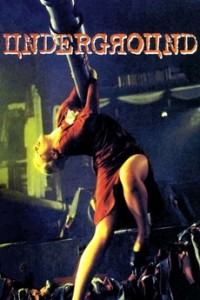

Though slightly trimmed by director-writer Emir Kusturica for American consumption, this riotous 167-minute satirical and farcical allegory about the former Yugoslavia from World War II to the postcommunist present is still marvelously excessive. The outrageous plot involves a couple of anti-Nazi arms dealers and gold traffickers who gain a reputation as communist heroes. One of them (Miki Manojlovic) installs a group of refugees in his grandfather’s cellar, and on the pretext that the war is still raging upstairs he gets them to manufacture arms and other black-market items until the 60s, meanwhile seducing the actress (Mirjana Jokovic) that his best friend (Lazar Ristovski) hoped to marry. Loosely based on a play by cowriter Dusan Kovacevic, this sarcastic, carnivalesque epic won the 1995 Palme d’Or at Cannes and has been at the center of a furious controversy ever since for what’s been called its pro-Serbian stance. (Kusturica himself is a Bosnian Muslim.) However one chooses to take its jaundiced view of history, it’s probably the best film to date by the talented Kusturica (Time of the Gypsies, Arizona Dream), a triumph of mise en scene mated to a comic vision that keeps topping its own hyperbole. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (Mar 1, 1998). — J.R.

After his first two features in the early 60s (The Love Game, The Five-Day Lover), Philippe de Broca, a former assistant to Francois Truffaut and Claude Chabrol, was taken by some to be a member of the French New Wave — an impression that was quickly undermined by the glossy commercial fare that followed, including this enjoyable 1964 thriller romp with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Francoise Dorleac. If memory serves, this is swell light entertainment — there’s a nice score by Georges Delerue, and the original screenplay was nominated for an Oscar — designed to autodestruct as soon as you see it. (JR)

Read more