From the Chicago Reader (October 23, 2003). — J.R.

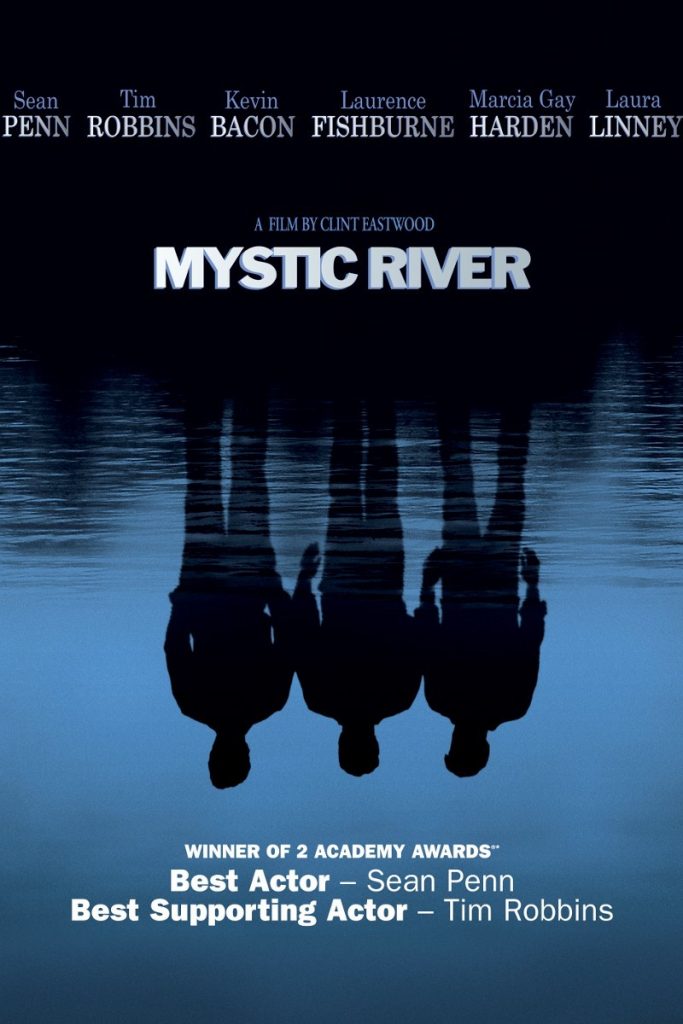

Mystic River

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Brian Helgeland

With Sean Penn, Tim Robbins, Kevin Bacon, Laurence Fishburne, Marcia Gay Harden, Kevin Chapman, Laura Linney, Adam Nelson, Emmy Rossum, and Cameron Bowen.

The critical community has spoken: Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River is a masterpiece and a profound, tragic statement about who we are and the inevitability of violence in our lives — a pitiless view, in which violence begets violence and the sins of the fathers pass to later generations.

Presumably these qualities are also in Dennis Lehane’s best-selling novel, which I haven’t read, but it’s the movie that’s drawing most of the superlatives from American critics. The acclaim started after the film premiered at Cannes, when much of the griping American press seemed to see it as a vindication of American filmmaking, an answer to the terrible state of cinema in general. Some of those critics may have seen it as a vindication of U.S. patriotism as well — one reason it’s likely to rack up plenty of Oscars.

The last Eastwood movie that provoked biblical language and allusions to Greek tragedy was Unforgiven (1992), which also saw violence as both awful and unavoidable — our destiny and perhaps even our birthright. Now the dark vision of Mystic River is being touted as a form of higher wisdom graced with noble feelings that for some reviewers mysteriously translates into high art. The New Yorker‘s David Denby, who can usually be counted on for such judgments, doesn’t disappoint: “Mystic River, with its gray, everyday light, is a work of art in a way that, say, The Big Sleep and Out of the Past, which were shaped as melodrama and shot in glamorous chiaroscuro, were not. Mystic River is as close as we are likely to come on the screen to the spirit of Greek tragedy (and closer, I think, than Arthur Miller has come on the stage).” If Denby had given it more thought, he might have put even Aeschylus (and his lighting schemes) second to Clint. I find less suspect the reviews that have linked Mystic River to opera — an art form that’s generally enhanced rather than reduced by melodrama.

But the larger issue isn’t the degree to which Eastwood’s movie qualifies as art. It’s why reviewers are so desperate to establish its artistic pedigree. Many debates have been waged in the past — often sparked by Pauline Kael — about whether Eastwood the director deserves to be considered an artist rather than a poseur or a popular entertainer. But since Kael herself often, and rightly, celebrated popular entertainment and certain forms of chicanery as legitimate art, there’s something peevish about her objections to him.

I have to assume that reviewers who get this worked up about how much a work of art is a work of art — and Denby is far from the only one — want to buttress some ideological and psychosexual program they fear won’t be taken seriously enough without the label of “art.” Since I have doubts about the ideological and psychosexual program of Mystic River — especially the part implying that the thirst for revenge is an honorable adult emotion — I should stress that Eastwood’s artistry is equally relevant to my argument. The success of Mystic River as melodrama and art is precisely what I mistrust about it, because that success comes with dubious baggage in tow — baggage that’s less obviously dubious than the Nazi propaganda served by Leni Riefenstahl’s artistry in Triumph of the Will but still consequential. If artistic effects are often enhanced by being perceived as artistic, propagandistic effects, regardless of the intent behind them, are often enhanced by not being perceived as propagandistic.

In any case, my ambivalence about the film makes me feel that none of the usual star ratings is adequate. I’ll grant that the film, despite some flaws involving plausibility and structure, can be called a masterpiece insofar as it’s the work of a master. But does that oblige me to conclude that it’s a must-see or even worth seeing? I’m not at all sure, because I find it both impossible and undesirable to separate the film from its contemporary resonance and social meanings.

I ran into a related problem with Jonathan Demme’s 1991 The Silence of the Lambs, a less artistically accomplished film. I thought there was something obscene about audiences’ delighted fascination with the evil and brilliant lunatic Hannibal Lecter gleefully killing without a shred of compunction, especially since some in those audiences seemed indifferent to the slaughter of innocent Iraqis that was going on at the same time. I couldn’t blame Demme or the story he was filming for that obscenity, since he wasn’t responsible for the delight with which his movie was received or the time at which it was released. Mystic River is too depressing to fill audiences with delight, but it does seem to validate questionable attitudes, especially an indifference to the suffering of innocent people and a willingness to shoot first and ask questions later.

A couple of fathers discuss baseball on a porch in their working-class Boston neighborhood, setting a tone of patriotic nostalgia. Around the corner three boys play stickball, lose their ball in a gutter, then turn to writing their names in the freshly laid cement of a sidewalk, Dave following Sean and Jimmy. A car arrives, and two men who claim to be police nab Dave for defacing public property. They hold him prisoner for several days, sexually abusing him until he escapes.

A quarter of a century later we catch up with these three boys as adults. Dave had written only the first two letters of his name in the cement before he was abducted — a brilliant literary conceit whereby “Da,” baby talk for “dad,” symbolizes his arrested development after his trauma (which the movie views as the only significant event in his life), just as the ball lost in the gutter symbolizes his eventual fate. Now he’s a conscientious father, though otherwise he’s fairly dysfunctional, socially and professionally. Tim Robbins’s performance — by far the most remarkable I’ve seen from him —conveys his character’s gnarled repression almost immediately through his voice and body language.

Jimmy (Sean Penn) is an ex-con who lords it over a few hoods, runs a neighborhood grocery, and seems like a fairly contented family man until his teenage daughter Katie (Emmy Rossum) is found brutally murdered with no apparent motive. Sean (Kevin Bacon), a police detective who investigates the murder with a colleague (Laurence Fishburne), has recently been deserted by his wife, though she periodically phones him only to say nothing.

My own favorite Eastwood “tragedy” is White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), partly because it has the guts to show John Huston, effectively played by Eastwood himself, as a stupid asshole as well as a macho charmer. Yet this is probably the least critically esteemed of Eastwood’s ambitious films, and one of the least commercially successful. I assume that what makes Unforgiven and Mystic River so much more popular is their capacity to fulfill the usual genre expectations — as a bloody western and a police procedural whodunit, respectively — and also fulfill art-movie expectations by reflecting on the genres, though without ever seriously challenging their macho underpinnings.

Because the whodunit in Mystic River isn’t solved until very late, we wind up sharing many of the doubts and uncertainties of some of the characters, particularly Jimmy, Sean, and Dave’s wife, Celeste (Marcia Gay Harden). This uncertainty is given much more poignance, significance, and force by something we hear Jimmy saying at one point to his dead daughter: “I know in my soul I contributed to your death — but I don’t know how.” This is precisely where the art-movie function kicks in, because insofar as we share these characters’ ignorance about the murder, we become morally implicated in some of their decisions.

Eventually we discover how Jimmy did in fact indirectly contribute to his daughter’s death, though this realization registers as secondary to his killing of Dave in the mistaken belief that Dave killed Katie. What bothers me most about Mystic River is the emotional, as opposed to logical, validation of this killing, a validation that reminds me of George W. Bush’s apparently proud indifference to the fate of the 152 prisoners executed while he was governor of Texas — he’s never shown any doubt about their guilt and even publicly mocked one woman’s plea to live, a decidedly unadult, not to mention un-Christian, attitude.

Jimmy promises to let Dave live if he’ll “tell the truth” and “admit” that he killed Katie, which forces Dave to lie. That Jimmy kills him anyway — not for lying but for supposedly telling the truth — isn’t allowed to interfere for a second with Jimmy’s status as tragic hero rather than pathetic, retarded monster. Dave, who committed a desperate, vengeful murder of his own around the time Katie was killed, is seen as pathetic and retarded because of his childhood trauma, though his victim is viewed as another bit of collateral damage that needn’t concern us; there’s a tacit assumption that because he was a sexual molester, he probably deserved to die.

Jimmy, whatever his failings, is allowed to stand tall. A desire for revenge –no matter how illogical, misguided, and ultimately disastrous its premises might be — is probably the most validated emotion in current American movies and current American politics. It’s seen as so noble and righteous that for some it justifies a loss of civil liberties, as well as capital punishment, holy wars, and collateral damage. Even if the wrong people die, at least we know our intentions were good. This is a form of popular psychosis, and it gives even such seemingly antithetical movies as Mystic River and Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill–Vol. 1 a grotesque kind of kinship. I hasten to add that the most winning aspect of Tarantino’s frenetic movie is that it doesn’t in any way pretend to be grown-up, whereas critics are claiming Eastwood’s movie has all the wisdom of his 70-odd years, if not the wisdom of Solomon.

Jimmy’s desire for revenge creates its own kind of collateral damage, yielding the film’s tragic conclusion. This might not bother me so much if revenge and payback weren’t so central to American action movies, especially those made over the past 30 years — a period that largely coincides with Eastwood’s career as an actor and encompasses many of the biggest successes of his two mentors, directors Sergio Leone and Don Siegel. (Siegel introduced us to the Dirty Harry character, whose stoical payback style and terse delivery were consciously emulated by at least two former Republican presidents.)

All of this is ratified in Sean Penn’s powerful and, indeed, artistic performance as Jimmy, which is probably as much of a milestone in his own career as Robbins’s performance is in his. Yet those who are rightly linking this performance to the tradition of Marlon Brando aren’t acknowledging the glamorized, liberal, narcissistic masochism that comes with it, which is just as instrumental in defining the character’s impact as righteous conservative vindictiveness. This tradition helps create a performance so powerful it makes me sick. And so powerful it even helps his character’s wife, Annabeth (Laura Linney), excuse the murder of Dave in what Newsweek‘s David Ansen has aptly called the Lady Macbeth scene. After all, Jimmy bares his naked torso to us, Christian tattoo and all, and he hurts as much as Brando with his own naked torso did. This is supposed to be enough to make us, like the dutiful Annabeth, love and respect him. After all, at least by implication, he’s Christ, though the only part of sinning humanity he seeks to forgive is himself.

One might counter that Eastwood is perfectly aware of the monstrousness of this conclusion and that the darkness of his film’s vision makes room for it. Maybe, but I don’t much care. Most of the critical appreciations of Mystic River I’ve read seem so smitten with the fatalistic and deterministic side of this scenario that Eastwood’s intentions don’t matter. He may have tried to cross tragic inevitability with some form of Christian forgiveness — of Jimmy, if not the child molesters — but if we’re doomed regardless of what we do or think, what’s the point of trying to clean up our act? We’re free of any obligation to act differently — yet also free to relish the nobility of our pain at the realization that we’ve done something wrong.

Also dismaying are Eastwood’s two-dimensional depictions of Celeste and Annabeth and his one-dimensional depiction of Sean’s wife — whom we don’t see and who scarcely exists on any level except as a thematic and structural prop. Apparently Sean wasn’t paying enough attention to her when they were together, though by the end of the film he’s learned his lesson. She’s there simply to provide some narrative symmetry and the basis for a redemptive, if highly qualified, happy ending.

Stuart Klawans, writing in the Nation, suggestively includes Mystic River among Eastwood’s westerns. But one thing that prevents the film from being an “adult western” like one of Anthony Mann’s in the 50s is the failure of the womenfolk to represent or express any alternative to the unreasoning violence of Jimmy and Dave. We’re asked to accept not only that Celeste has known nothing about Dave’s childhood trauma until recently, though she grew up in the same neighborhood, but that she’s so terrified by his aberrant behavior, even after years of being married to him, that she thinks he murdered Katie and is willing to say so to Jimmy, sealing his doom. And Annabeth is so fully in denial about Jimmy being guilty of anything that she sees it as her sacred duty to assure him he’s right even when he’s wrong.

Is this tragic inevitability or misogyny? Or is it maybe some of both, with redemptive love and the equivalent of operatic arias thrown in as validation? Whatever it is, it’s the American way, and Eastwood has been elected its official commentator. Maybe he’s telling us we’re wrong even when we’re right, but he’s made it too easy to read that message in reverse.