Commissioned by the French quarterly Trafic for their spring 2020 issue. — J.R.

The rhythmic clapping resonates inside these

walls, which are hard and glossy as coal: Come-

on! Start-the-show! Come-on! Start-the-show!

The screen is a dim page spread before us,

white and silent. The film has broken, or a

projector bulb has burned out. It was difficult

even for us, old fans who’ve always been at

the movies (haven’t we?) to tell which before

the darkness swept in.

— from the last page of Gravity’s Rainbow

To begin with a personal anecdote: Writing my first book (to be published) in the late 1970s, an experimental autobiography titled Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (Harper & Row, 1980), published in French as Mouvements: Une vie au cinéma (P.O.L, 2003), I wanted to include four texts by other authors — two short stories (“In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” by Delmore Schwartz, “The Secret Integration” by Thomas Pynchon) and two essays (“The Carole Lombard in Macy’s Window” by Charles Eckert, “My Life With Kong” by Elliott Stein) — but was prevented from doing so by my editor, who argued that because the book was mine, texts by other authors didn’t belong there. My motives were both pluralistic and populist: a desire both to respect fiction and non-fiction as equal creative partners and to insist that the book was about more than just myself and my own life. Because my book was largely about the creative roles played by the fictions of cinema on the non-fictions of personal lives, the anti-elitist nature of cinema played a crucial part in these transactions.`

In the case of Pynchon’s 1964 story — which twenty years later, in his collection Slow Learner, he would admit was the only early story of his that he still liked — the cinematic relevance to Moving Places could be found in a single fleeting but resonant detail: the momentary bonding of a little white boy named Tim Santora with a black, homeless, alcoholic jazz musician named Carl McAfee in a hotel room when they discover that they’ve both seen Blood Alley (1955), an anticommunist action-adventure with John Wayne and Lauren Bacall, directed by William Wellman. Pynchon mentions only the film’s title, but the complex synergy of this passing moment of mutual recognition between two of its dissimilar viewers represented for me an epiphany, in part because of the irony of such casual camaraderie occurring in relation to a routine example of Manichean Cold War mythology. Moreover, as a right-wing cinematic touchstone, Blood Alley is dialectically complemented in the same story by Tim and his friends categorizing their rebellious schoolboy pranks as Operation Spartacus, inspired by the left-wing Spartacus (1960) of Kirk Douglas, Dalton Trumbo, and Stanley Kubrick.

For better and for worse, all of Pynchon’s fiction partakes of this populism by customarily defining cinema as the cultural air that everyone breathes, or at least the river in which everyone swims and bathes. This is equally apparent in the only Pynchon novel that qualifies as hackwork, Inherent Vice (2009), and the fact that Paul Thomas Anderson’s adaptation of it is also his worst film to date — a hippie remake of Chinatown in the same way that the novel is a hippie remake of Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald — seems logical insofar as it seems to have been written with an eye towards selling the screen rights. As Geoffrey O’Brien observed (while defending this indefensible book and film) in the New York Review of Books (January 3, 2015), “Perhaps the novel really was crying out for such a cinematic transformation, for in its pages people watch movies, remember them, compare events in the ‘real world’ to their plots, re-experience their soundtracks as auditory hallucinations, even work their technical components (the lighting style of cinematographer James Wong Howe, for instance) into aspects of complex conspiratorial schemes.” (Despite a few glancing virtues, such as Josh Brolin’s Nixonesque performance as “Bigfoot” Bjornsen, Anderson’s film seems just as cynical as its source and infused with the same sort of misplaced would-be nostalgia for the counterculture of the late 60s and early 70s, pitched to a generation that didn’t experience it, as Bertolucci’s Innocents: The Dreamers.)

From The Crying of Lot 49’s evocation of an orgasm in cinematic terms (“She awoke at last to find herself getting laid; she’d come in on a sexual crescendo in progress, like a cut to a scene where the camera’s already moving”) to the magical-surreal guest star appearance of Mickey Rooney in wartime Europe in Gravity’s Rainbow, cinema is invariably a form of lingua franca in Pynchon’s fiction, an expedient form of shorthand, calling up common experiences that seem light years away from the sectarianism of the politique des auteurs. This explains why his novels set in mid-20th century, such as the two just cited, when cinema was still a common currency cutting across classes, age groups, and diverse levels of education, tend to have the greatest number of movie references. In Gravity’s Rainbow — set mostly in war-torn Europe, with a few flashbacks to the east coast U.S. and flash-forwards to the contemporary west coast — this even includes such anachronistic pop ephemera as the 1949 serial King of the Rocket Men and the 1955 Western The Return of Jack Slade (which a character named Waxwing Blodgett is said to have seen at U.S. Army bases during World War 2 no less than twenty-seven times), along with various comic books.

Significantly, “The Secret Integration”, a title evoking both conspiracy and countercultural utopia, is set in the same cozy suburban neighborhood in the Berkshires from which Tyrone Slothrop, the wartime hero or antihero of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), aka “Rocketman,” springs, with his kid brother and father among the story’s characters. It’s also the same region where Pynchon himself grew up. And Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon’s magnum opus and richest work, is by all measures the most film-drenched of his novels in its design as well as its details—so much so that even its blocks of text are separated typographically by what resemble sprocket holes. Unlike, say, Vineland (1990), where cinema figures mostly in terms of imaginary TV reruns (e.g., Woody Allen in Young Kissinger) and diverse cultural appropriations (e.g., a Noir Center shopping mall), or the post-cinematic adventures in cyberspace found in the noirish (and far superior) east-coast companion volume to Inherent Vice, Bleeding Edge (2013), cinema in Gravity’s Rainbow is basically a theatrical event with a social impact, where Fritz Lang’s invention of the rocket countdown as a suspense device (in the 1929 Frau im mond) and the separate “frames” of a rocket’s trajectory are equally relevant and operative factors. There are also passing references to Lang’s Der müde Tod, Die Nibelungen, Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, and Metropolis — not to mention De Mille’s Cleopatra, Dumbo, Freaks, Son of Frankenstein, White Zombie, at least two Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musicals, Pabst, and Lubitsch — and the epigraphs introducing the novel’s second and third sections (“You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood. –-Merian C. Cooper to Fay Wray” and “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas any more…. –- Dorothy, arriving in Oz”) are equally steeped in familiar movie mythology.

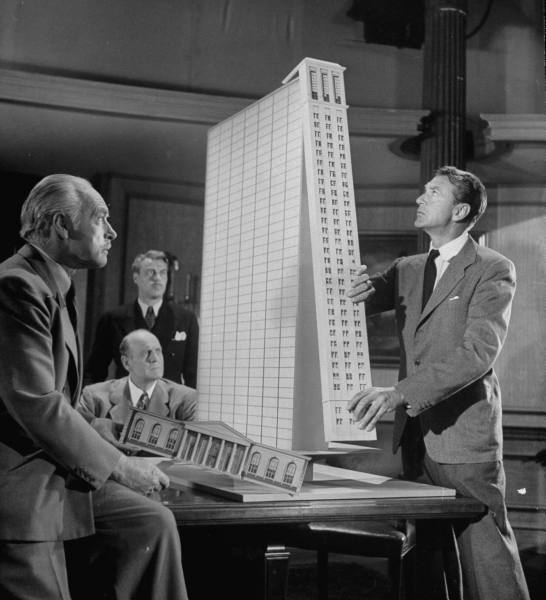

These are all populist allusions, yet the bane of populism as a rightwing curse is another near-constant in Pynchon’s work. The same ambivalence can be felt in the novel’s last two words, “Now everybody — “, at once frightening and comforting in its immediacy and universality. With the possible exception of Mason & Dixon (1997), every Pynchon novel over the past three decades — Vineland, Against the Day (2006), Inherent Vice, and Bleeding Edge — has an attractive, prominent, and sympathetic female character betraying or at least acting against her leftist roots and/or principles by being first drawn erotically towards and then being seduced by a fascistic male. In Bleeding Edge, this even happens to the novel’s earthy protagonist, the middle-aged detective Maxine Tarnow. Given the teasing amount of autobiographical concealment and revelation Pynchon carries on with his public while rigorously avoiding the press, it is tempting to see this recurring theme as a personal obsession grounded in some private psychic wound, and one that points to sadder-but-wiser challenges brought by Pynchon to his own populism, eventually reflecting a certain cynicism about human behavior. It also calls to mind some of the reflections of Luc Moullet (in “Sainte Janet,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 86, août 1958) aroused by Howard Hughes’ and Josef von Sternberg’s Jet Pilot and (more incidentally) by Ayn Rand’s and King Vidor’s The Fountainhead whereby “erotic verve” is tied to a contempt for collectivity — implicitly suggesting that rightwing art may be sexier than leftwing art, especially if the sexual delirium in question has some of the adolescent energy found in, for example, Hughes, Sternberg, Rand, Vidor, Kubrick, Tashlin, Jerry Lewis, and, yes, Pynchon.

One of the most impressive things about Pynchon’s fiction is the way in which it often represents the narrative shapes of individual novels in explicit visual terms. V, his first novel, has two heroes and narrative lines that converge at the bottom point of a V; Gravity’s Rainbow, his second — a V2 in more ways than one — unfolds across an epic skyscape like a rocket’s (linear) ascent and its (scattered) descent; Vineland offers a narrative tangle of lives to rhyme with its crisscrossing vines, and the curving ampersand in the middle of Mason & Dixon suggests another form of digressive tangle between its two male leads; Against the Day, which opens with a balloon flight, seems to follow the curving shape and rotation of the planet.

This compulsive patterning suggests that the sprocket-hole design in Gravity’s Rainbow’s section breaks is more than just a decorative detail. The recurrence of sprockets and film frames carries metaphorical resonance in the novel’s action, so that Franz Pökler, a German rocket engineer allowed by his superiors to see his long-lost daughter (whom he calls his “movie child” because she was conceived the night he and her mother saw a porn film) only once a year, at a children’s village called Zwölfkinder, and can’t even be sure if it’s the same girl each time:

So it has gone for the six years since. A daughter

a year, each one about a year older, each time

taking up nearly from scratch. The only continuity

has been her name, and Zwölfkinder, and Pökler’s

love—love something like the persistence of

vision, for They have used it to create for him the

moving image of a daughter, flashing him only

these summertime frames of her, leaving it to him

to build the illusion of a single child—what would

the time scale matter, a 24th of a second or a year

(no more, the engineer thought, than in a wind

tunnel, or an oscillograph whose turning drum

you can speed or slow at will…)?

***

Cinema, in short, is both delightful and sinister — a utopian dream and an apocalyptic nightmare, a stark juxtaposition reflected in the abrupt shift in the earlier Pynchon passage quoted at the beginning of this essay from present tense to past tense, and from third person to first person. Much the same could be said about the various displacements experienced while moving from the positive to the negative consequences of populism.

Pynchon’s allegiance to the irreverent vulgarity of kazoos sounding like farts and concomitant Spike Jones parodies seems wholly in keeping with his disdain for David Raksin and Johnny Mercer’s popular song “Laura” and what he perceives as the snobbish elitism of the Preminger film it derives from, as expressed in his passionate liner notes to the CD compilation “Spiked!: The Music of Spike Jones” a half-century later:

The song had been featured in the 1945 movie of the same name, supposed to evoke the hotsy-totsy social life where all these sophisticated New York City folks had time for faces in the misty light and so forth, not to mention expensive outfits, fancy interiors, witty repartee — a world of pseudos as inviting to…class hostility as fish in a barrel, including a presumed audience fatally unhip enough to still believe in the old prewar fantasies, though surely it was already too late for that, Tin Pan Alley wisdom about life had not stood a chance under the realities of global war, too many people by then knew better.

Consequently, neither art cinema nor auteur cinema figures much in Pynchon’s otherwise hefty lexicon of film culture, aside from a jokey mention of a Bengt Ekerot/Maria Casares Film Festival (actors playing Death in The Seventh Seal and Orpheus) held in Los Angeles — and significantly, even the “underground”, 16-millimeter radical political filmmaking in northern California charted in Vineland becomes emblematic of the perceived failure of the 60s counterculture as a whole. This also helps to account for why the paranoia and solipsism found in Jacques Rivette’s Paris nous appartient and Out 1, perhaps the closest equivalents to Pynchon’s own notions of mass conspiracy juxtaposed with solitary despair, are never mentioned in his writing, and the films that are referenced belong almost exclusively to the commercial mainstream, unlike the examples of painting, music, and literature, such as the surrealist painting of Remedios Varo described in detail at the beginning of The Crying of Lot 49, the importance of Ornette Coleman in V and Anton Webern in Gravity’s Rainbow, or the visible impact of both Jorge Luis Borges and William S. Burroughs on the latter novel. (1) And much of the novel’s supply of movie folklore — e.g., the fatal ambushing of John Dillinger while leaving Chicago’s Biograph theater — is mainstream as well.

Nevertheless, one can find a fairly precise philosophical and metaphysical description of these aforementioned Rivette films in Gravity’s Rainbow: “If there is something comforting — religious, if you want — about paranoia, there is still also anti-paranoia, where nothing is connected to anything, a condition not many of us can bear for long.” And the white, empty movie screen that appears apocalyptically on the novel’s final page—as white and as blank as the fusion of all the colors in a rainbow — also appears in Rivette’s first feature when a 16-millimeter print of Lang’s Metropolis breaks during the projection of the Tower of Babel sequence.

Is such a physically and metaphysically similar affective climax of a halted film projection foretelling an apocalypse a mere coincidence? It’s impossible to know whether Pynchon might have seen Paris nous appartient during its brief New York run in the early 60s. But even if he hadn’t (or still hasn’t), a bitter sense of betrayed utopian possibilities in that film, in Out 1, and in most of his fiction is hard to overlook. Old fans who’ve always been at the movies (haven’t we?) don’t like to be woken from their dreams.

Footnote

- For this reason, among others, I’m skeptical about accepting the hypothesis of the otherwise reliable Pynchon critic Richard Poirier that Gravity’s Rainbow’s enigmatic references to “the Kenosha Kid” might allude to Orson Welles, who was born in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Steven C. Weisenburger, in A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion (Athens/London: The University of Georgia Press, 2006), reports more plausibly that “the Kenosha Kid” was a pulp magazine character created by Forbes Parkhill in Western stories published from the 1920s through the 1940s. Once again, Pynchon’s populism trumps— i.e. exceeds — his cinephilia.