This appeared in the July 26, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

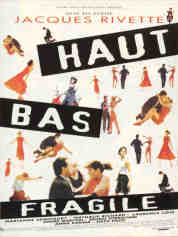

Up Down Fragile

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Laurence Côte, Marianne Denicourt, Nathalie Richard, Pascal Bonitzer, Christine Laurent, and Rivette

With Côte, Denicourt, Richard, Anna Karina, André Marcon, Bruno Todeschini, Wilfre Benaiche, Enzo Enzo, and the voice of László Szabó

The inspiration of Up Down Fragile? The MGM low-budget films of the 50s that were shot in four or five weeks on sets left over from other films. In particular, a Stanley Donen movie, Give a Girl a Break [1953], a simple film shot in next to no time with short dance numbers. — Jacques Rivette in an interview

Entertainment does not…present models of utopian worlds, as in the classic utopias of Sir Thomas More, William Morris, et al. Rather the utopianism is contained in the feelings it embodies. It presents, head-on as it were, what utopia would feel like rather than how it would be organized. — Richard Dyer, “Entertainment and Utopia”

Out of Jacques Rivette’s 17 features to date — in which I include his 12-hour serial Out 1 (1970) as well as both parts of his Jeanne la pucelle (1994) — 9 are set in contemporary Paris. And few other movies I can think of infuse that city with the same kind of distilled, everyday poetry. For Rivette, Paris is a city of secrets and puzzles, of hidden alliances and privileged locations — a park bench here, a courtyard there — forming the nexus of magical encounters.

In a way, the title of Rivette’s Paris Belongs to Us says it all. Solitude and togetherness are the two great themes of his work, often intertwined like the melodic lines of a fugue, and Paris often seems to function as the orchestra that performs and places those melodies, charts their coexistence and their interplay. A city that in many ways seems designed, choreographed, and even lit to provide the settings for romantic musicals — as evidenced in such films as An American in Paris and Funny Face — Paris belongs to loners, couples, and groups, all of whom bring something sad or euphoric to the city as well as take something away from it. It’s a kind of give-and-take we often associate with characters in a musical, interacting singly or collectively but always romantically with their environment.

Haut bas fragile (“Up Down Fragile”) — a 1995 release receiving its U.S. theatrical premiere at the Music Box this week because no New York theater has been willing to give it a run — is the first of Rivette’s films to literally profit from Paris’s ideal qualifications as the setting for a musical. One of the privileged sites is the alleyway outside a delivery service called Vitébien (which one could translate roughly as “Quick ‘n’ Spiffy”), where Ninon (Nathalie Richard), one of the three youthful heroines, parks her moped and chats with her coworkers between deliveries (the movie’s title alludes to the instructions often stamped on parcels). Because the film is set during the summer, doors and windows tend to remain open, and part of what makes this spot a magical nexus, with pathways stretching out in all directions, are such proximate details as an upstairs neighbor who calls down to people in the alley and adjacent office and a nearby atelier, where Roland — the closest thing this movie has to a male hero (and André Marcon is a dead ringer at moments for Gene Kelly) — works as a set designer.

The location reminds me of the courtyard in Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange and other such hangouts in populist French movies of the 30s. But if this alleyway seems like the relaxed setting for a proletarian musical, other locations suggest different classes. The movie’s upper-crust heroine, Louise (Marianne Denicourt) — who’s just settling in at a Paris hotel after several years in a coma in a provincial clinic — tends to gravitate toward decorous settings in and around parks; one of her favorite spots is a bench on the rue du Moulin de la Pointe that seems to have been designed for Leslie Caron. The third heroine, Ida (Laurence Côte), is neither working-class nor wealthy: she’s a librarian at the Library of Decorative Arts, where Roland sometimes goes for research. Like Louise she favors parks, but less decorous portions of them. We often find her at a stand selling crepes and hot dogs, where early in the movie she flees from a crazy-looking man named Monsieur Paul who asks, “Haven’t I seen you before?” (Rivette himself plays the man, and the fact that he cast Côte in The Gang of Four may be part of the joke. The fact that in real life he’s a solitaire like her character — her doppelgänger in a way — may be equally pertinent.)

Ninon and Louise get to know each other, and both of them get to know Roland; each has a musical number with the other two. But Ida tends to remain on the fringes of their separate and interlocking stories, in musical as well as narrative terms. All three actresses created their own characters — a procedure Rivette also followed in Out 1 and Celine and Julie Go Boating. And just as Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto are solitaires in Out 1 and Julie is one in Celine and Julie before she meets Celine, Ida in Up Down Fragile might be described as someone who’d like to be in a musical but can’t because she doesn’t yet know who she is. The adopted daughter of provincial parents whose letters she doesn’t answer, she’s obsessed with fantasies about who her real mother might be and with tracking down a song from her early childhood, of which she remembers only fragments. (Eventually her obsession leads to a meeting with Sarah, a cabaret singer, played by Anna Karina, whom we’ve already seen in scenes with Ninon and Louise.) Narratively and musically, Ida’s in a perpetual state of becoming — the only creature to whom she’s attached is a cat. Meanwhile the other lines in the fugue are the processes by which Ninon and Louise acquire romance and friendship and thereby work their way into musical numbers, all of them various kinds of duets.

A few glosses to the quotations at the head of this review: Apparently the only set in Up Down Fragile “left over” from another film — indeed, the only set at all — is Roland’s atelier, which I’m told is the studio soundstage Rivette used for interiors in the two previous features comprising Jeanne la pucelle. The only other relevance of Give a Girl a Break to Up Down Fragile of which I’m aware is the fact that each film has three heroines and three interlocking mini plots. As for the Richard Dyer quote, I think one could argue that Up Down Fragile not only tells us a lot about what utopia would feel like, it also tells us a little about how it would be organized.

A whole hour of Up Down Fragile passes before the first song-and-dance number. But during that hour Rivette takes a lot of steps — in metaphysical, stylistic, musical, directorial, and choreographic terms — tracing the passage between real life and musical numbers. The same sort of steps are taken throughout the remaining hour and a half of Up Down Fragile, sometimes leading up to or away from musical numbers, sometimes not.

The metaphysical, stylistic, musical, and directorial steps Rivette takes have everything to do with his legacy as a film critic, despite the fact that he wrote and published criticism only between 1950 and 1969. As the most indefatigable moviegoer of all the Cahiers du Cinéma critics who became directors — a distinguished group including Olivier Assayas, Leos Carax, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Luc Moullet, Eric Rohmer, Andre Téchiné, and François Truffaut, among others — he knows MGM musicals like the back of his hand. But he doesn’t express his knowledge in specific homages or references the way an American cinephile normally would. For Rivette this knowledge is precious because it enhances and poeticizes real life, not because it offers an alternative or escape.

Consequently the movie has a documentary roughness — a respect for real durations, for moments that are empty as well as full — that would have been unthinkable in a 50s MGM musical. Moreover, none of the songs is especially memorable, either melodically or in terms of performance (it’s no surprise that there isn’t a sound track album), nor is any of the dancing up to snuff by Hollywood standards. Indeed, some European critics have dismissed Up Down Fragile for precisely these reasons, and I have little doubt many of their American counterparts would do the same.

Tough luck for them. Though I’m sure the movie would be better if it had a better score, I’m less certain about the virtues that “professional” dancers and singers would have provided; I suppose it’s all a matter of how they’d be used. When Louise finally gets acquainted with Lucien (Bruno Todeschini) — a lovable nebbish who’s been awkwardly shadowing her at the behest of her wealthy offscreen father (László Szabó) — their romance finally blossoms inside and nearby a park pavilion in a song and a series of struck poses and dance turns, all of them delightfully amateurish.

This number, my favorite in the movie, reminds me of both a particular park pavilion and the irrepressible youthful giddiness in I Love Melvin (1953), a deliciously modest MGM musical with Donald O’Connor and Debbie Reynolds directed by Don Weis. The fact that Todeschini has none of O’Connor’s technique as a dancer and that Denicourt has none of Reynolds’s slickness as a singer isn’t a liability but one of Rivette’s givens, and he builds the number around his actors just as sturdily as Weis built the numbers of I Love Melvin around his. In Rivette’s case, the vulnerability, even fragility of his performers is every bit as important as the professional polish of Weis’s; in both cases, the directors are using their actors as instruments for conveying euphoria. (I must confess that I also love what Joseph L. Mankiewicz did with nonsingers Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons in Guys and Dolls.)

O’Connor’s number in the pavilion in I Love Melvin is a virtuoso turn performed on roller skates; Nathalie Richard in Up Down Fragile — the closest thing to a real dancer in Rivette’s movie — makes some of her deliveries on Rollerblades, quite gracefully but without performing any of O’Connor’s awesome acrobatics. Is O’Connor automatically a “better” performer than Richard, or I Love Melvin a “better” movie than Up Down Fragile? Criticizing the performances here is a bit like complaining that Thelonious Monk lacked the piano technique of Art Tatum; maybe so, but Monk still had all he needed to say what he wanted to say. Or as Duke Ellington once put it, more succinctly, “If it sounds good, it is good.”

Rivette’s numbers seem closer to life than Weis’s not only because his performers are less polished but partly because he dares to prolong some of Lucien’s and Louise’s dance moves after the music stops, providing one kind of pathway away from the euphoric moment, and partly because he uses a real location instead of a studio set. But surely other and more mysterious stylistic differences are at play as well; in ways that are difficult to pinpoint, a whole lifetime of moviegoing seems to lurk behind the pleasures offered by this movie, a trait it shares with Celine and Julie Go Boating.

Admittedly, the cultivation and appreciation of technique — human as well as cinematic — stand solidly behind the glory of the Hollywood musical, and we’d all be much poorer without it. But what Rivette has that his American critical and directorial counterparts often lack is a poetic and abstract appreciation of what that technique yields and what that glory consists of, especially in relation to everyday life — an appreciation of the dialectic between reality and fantasy that’s always been behind the potency of French cinema. That same dialectic also inspired Godard’s third feature, A Woman Is a Woman (1960), which he noted at the time was conceived as “a neorealist musical.” “It’s a complete contradiction,” he admitted, “but this is precisely what interested me in the film. It may be an error, but it’s an attractive one.” In the same interview he concluded, “The film is not a musical. It’s the idea of a musical.”

A Woman Is a Woman has plenty of glories — rent the widescreen video sometime and you’ll see what I mean — but Godard is right: it isn’t a musical. Up Down Fragile, which derives in a way from the same idea, is a musical, however, because ultimately it practices what Godard’s film only preaches, embodies what A Woman Is a Woman only theorizes about. Sometimes it’s a matter of Rivette stylizing movement — the actors’ as well as the camera’s — and often it’s simply a matter of imparting emotion; a great deal of the film’s solidity as a musical has to do with the way it explores the joys and sorrows of being alone and of being with someone else. But most often it’s Rivette’s acute sense of what steps need to be taken to approach or retreat from a euphoric musical moment, whether romantic or friendly — how to find such steps, how to execute them, and above all how to place them in the midst of an ordinary summer afternoon or evening in Paris. In other words, not only a sense of what utopia might feel like, but also how it might be organized.