From the Village Voice (April 25, 1971). This was the first piece I ever published there, thanks to Andrew Sarris, and I’ve done a light edit (in October 2012) in order to make it a little more bearable to me. The “Indian girl” [sic] mentioned here, who subsequently became a very good friend, was Munni Kabir; as Nasreen Munni Kabir, she is identified today on Wikipedia as an author and TV producer, based in the U.K., and about ten years ago, I saw her again in London when she came to a public discussion I was having with Geoff Andrew about the short films of Kiarostami.

I believe I was mistaken about the seasonal setting of the Dostoevsky story, and apologized profusely about this to Bresson himself when he expressed interest in reading this article (which he conveyed to me via Munni, along with his address) and I sent him a copy, along with a note; I still have a copy of his gracious thank-you note, sent to me in Alabama, including his assurance that my error wasn’t very important….My subsequent encounters with (or, more precisely, sightings of) Bresson in Paris occurred at a screening of Luchino Visconti’s White Nights at the Cinematheque’s auditorium on Rue d’Ulm, a private screening of Susan Sontag’s Promised Lands, and two successive private screenings of Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac with members of his cast and crew.

One can access Four Nights of a Dreamer, incidentally, with English subtitles, at https://ok.ru/video/7321995119175. — J.R.

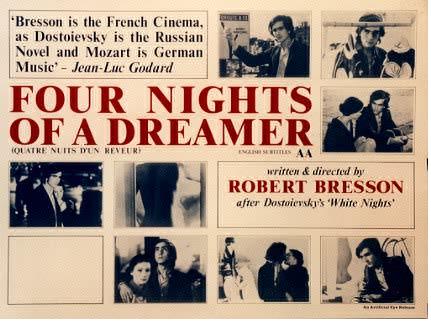

PARIS, France -– Nothing happens accidentally in a Bresson film, yet my opportunity to work as an extra in the latest one, Quatre Nuits d’un rêveur (Four Nights of a Dreamer), was completely fortuitous. A cinephile living in Paris who, like many others, makes regular treks to the Cinémathèque Française, I arrived one evening to attend a screening of Otto Preminger’s Advise and Consent. I knew that Bresson was making a film, because I’d already heard enthusiastic reports about it from Annette Michelson, who had watched a great deal of the shooting a month earlier. I vaguely knew that it was an adaptation of Dostoevsky’s story “White Nights” which — like Bresson’s last film, Une Femme Douce, also taken from a Dostoevsky story –- relocates the action in contemporary Paris. But nothing was further from my mind than this limited information when I entered the Cinémathèque, bought my 36-cent ticket, sat in the front row, and was asked by a young Frenchman, along with several others, whether I wanted to be in a Bresson film. “Of course!” I said. And two and a half hours later I was on my way to an address on Paul Doumer, a few blocks away, where the shooting was taking place.

Watching a Bresson film, whether it be the taut closet dramas of Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne or A Man Escaped, or the harsh rural fables of Au Hasard Balthazar or Mouchette, one is always in the presence of secrets, of personalities withheld so that an emotional purity might shine through their absences, of hermetic conclusions modeled into beautiful objects of contemplation. Not only have I been unable to discover those secrets, I’ve also been unwilling to look for them. The sheer aloneness of Bresson with his materials is something to be respected, particularly because any penetration of this mystery is bound to be an interruption.

It is not easy to make a film of the sort that one expects from Bresson, and his difficulties in making this one extend far beyond the two nights with the crew: as I write, some months later, his film is facing new budgetary problems, and recently the sound-mixing had to be temporarily postponed. With luck, the film may be completed in time to appear at the Cannes Festival, or at least at the New York Film festival next fall, but at present nothing is certain. Not having seen a single frame of the footage, I can give no indication of what the film will look like. A quick comparison of Dostoevsky’s story with the shooting script – the latter lent to me by a Indian girl who assisted on the film, makes it clear that Bresson has respected the contours of the original; but what he is to make of these contours is anyone’s guess.

“White Nights,” one of Dostoevsky’s earliest stories, at first glance seems to defy Bressonian transcription: a tale of young rapture, unrequited love, and loneliness, it exudes the same kind of pathos as Chaplin’s City Lights. When Visconti filmed the story in 1957, much of this pathos was dissipated by a florid use of Marcello Mastroianni and Maria Schell as the leads, and what was left was mainly contained in an elaborately contrived set and a sumptuous snowfall that occurs in the final reels. Bresson, on the other hand, has stuck to the habits of using non-professional actors and natural locations, and as far as I can tell makes about as much use of snow as Dostoevsky, who set his story in springtime.

When I arrived at the address on Avenue Paul Doumer, a shot was already being prepared. The crew was rather small, and even if one included all the extras and bystanders (of whom there weren’t very many), a minimal amount of cold sidewalk was being used. Before long, shooting began of a short scene between the two central characters, Marthe and Jacques, as they look up at the moon. The actors, Isabelle Weingarten and Guillaume des Forêts, had quintessential Bressonian faces pure, sculptural, and transparent. They stood in front of an artificial tree, a trunk placed there for the shot that taped off into nothing above camera range. Bresson was standing next to the camera and calling out instructions, but one wasn’t immediately aware of him as a directorial presence.While everything taking place in front of the camera was obviously his doing, one eventually became aware of him not so such as a “center” of various activities as the web binding these activities together. (More than three hours later, while talking to another extra, I discovered that he had no idea which director in the crowd had been directing him, since all the instructions had been relayed to him by other people.) More noticeably active was a woman named Mylène, the assistant director, who conveyed many of the orders, placed the extras, and, in the next shot, tapped us on the shoulder when we were to start walking across the sidewalk. [Note: This was Mylène van der Mersch, a Belgian woman who assisted Bresson on all of his last pictures and became his wife.]

The latter shot went through no fewer than 11 takes; it was a rather complicated one, involving an abrupt entrance by Marthe into the frame, an embrace of Jacques, and an abrupt exit while a stream of extras pass by on both sides. (When I came to read the Dostoevsky story much later, I discovered that this shot conveyed the climactic moment in the plot.) The lights and camera were set up half a block from the previous shot, and Bresson began by rehearsing the shot without extras, making occasional adjustments in the lighting and framing; then he brought us into camera range for a few more rehearsals before starting the first take. His principal direction of us was the repeated request, “Plus lentement!” (“More slowly!”), although at one point he called an extra over and, smiling, said, “You like to walk fast. All right, walk fast.” After each take, we walked back to our original positions and waited for the signal to start up again. After a while, the experience became something akin to a recurring dream; each time I passed Marthe and Jacques I could only be half-aware of them, even though the narrowness of the sidewalk caused me to brush against Jacques most of the times I passed him. The disadvantage of “acting,” even as an extra, is that one must forfeit the privileges of a spectator; so it was not always apparent to me why Bresson asked for another take, although it seemed to be usually a matter of the tempo and rhythm of the movements of Marthe and Jacques.

The next shot was taken from approximately the same camera angle, but required a flow of extras from the opposite direction. Once again, there were many retakes. My girlfriend had arrived by this time, and after one of the takes, Bresson asked her not to smile; later on, I managed to blow another one while running around in search of a misplaced overcoat. Finally everything broke up around 4 a.m.; the extras were asked to call the next day to find out the new shooting locations.

The next night proved to be more adventurous. Soon after I arrived at the first location, across from the Seine near Pont-Neuf, I was carried with several other extras to Pont de l’Alma, where we boarded an enormous bateau-mouche (tourist boat) along with the rest of the film crew. I was told that a lot of popular music was being used on the soundtrack -– a rare departure for Bresson –- and at one point in the film, Marthe and Jacques hear some bossa nova coming from a boat that passes by on the Seine; the shots of Marthe and Jacques had already been filmed, but Bresson wanted a linking shot of the Brazilian musicians on the boat. For budgetary reasons, the filming could take place only during one of the boat’s regularly scheduled excursions, so before we knew it, a steady influx of tourists was flowing onto the main deck, causing the film people to retreat further and further toward the back.The four musicians started to play and sing, and various kinds of confusion developed while Bresson framed them with his viewfinder; at one point, a heavy piece of lighting equipment fell on the foot of a middle-aged American woman, causing a few moments of pandemonium and outrage.

By the time the boat had left the dock, Bresson, the musicians, and most of the crew had gone to the bottom deck. It eventually became clear that extras wouldn’t be needed in this shot, so I sat down on the steps leading to the bottom deck and watched the shooting. From this vantage point, the situation on the boat seemed genuinely schizophrenic: on the upper deck, a crowd of tourists were treated to a trilingual recorded patter about points of interest along the river, while on the lower deck the Brazilians were singing and playing in unison with a tape recording of their song which kept going out of synch: the ensuing cacophony was unbelievable. Technical difficulties abounded, and on several occasions, when the boat was passing a lighted area on the shore and Bresson called out, “Moteur!”, one or more of the crew wasn’t ready and the shooting began too late.

After the boat docked, we learned that only four extras were needed for the remaining scenes; by luck, I was chosen as one of them. With the other three, I accompanied the crew to a plastic bistro a short distance from the Crazy Horse Saloon, where we were all treated to a free meal (Bresson seemed to be the only absent member). An hour later, we drove to the front of a modern, moderately expensive-looking apartment house on Rue du Longchamp, not far from the Bois de Boulogne. It was about 12:30 now, and most of the crew waited in the ear-pinching cold while the others set up the lights and camera equipment. Including extras, there were barely only a dozen of us here, and we spoke in whispers so as not to disturb the sleeping neighborhood; police gazed out at us morosely from a van that passed at regular intervals. Isabelle Weingarten asked to borrow my Village Voice, confessing that she didn’t know much English. Looking at my battered copy, she appeared as much like a self-contained Bresson heroine as she did during the takes.

Finally, the equipment was ready – the camera set up across the street from the apartment house, Marthe and Jacques preparing to enter the foreground of the shot to say goodnight while the other extras and I traversed the opposite sidewalk.Two of the extras were giggly French girls recruited by one of the second assistants as they were walking off the tourist boat; both had to call their mothers from the bistro to get permission to stay out this late. The girl who accompanied me remarked during one of the takes, “J’aime l’atmosphère du cinema. C’est trés charmant et interessant.” When the takes were completed, the other male extra and I switched coats (the girls likewise) so we could walk in the background of another shot, which had the same camera set-up. Throughout the shooting, Bresson was calm, poker-faced, and so wholly absorbed in the work that the cold didn’t seem to affect him. At one point between takes, he walked to the end of the block by himself and then came slowly back, apparently working something out in his mind.When he returned, he seemed as much a stranger in the small group as he did when he left. Everyone else seemed tired, petulant, and eager to be finished for the day. Finally, around 2:30, the shooting stopped and we all went home to sleep.