From the Chicago Reader (May 27, 1994). — J.R.

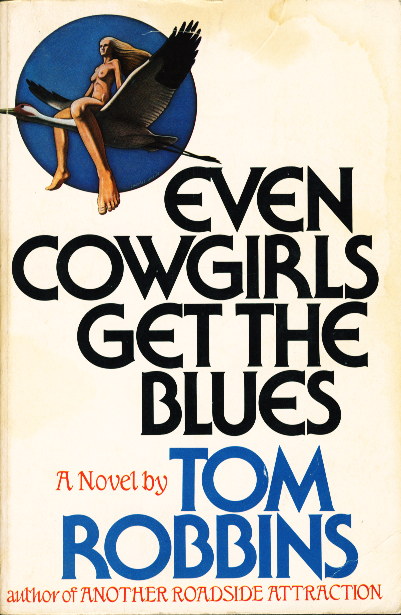

** EVEN COWGIRLS GET THE BLUES

(Worth seeing)

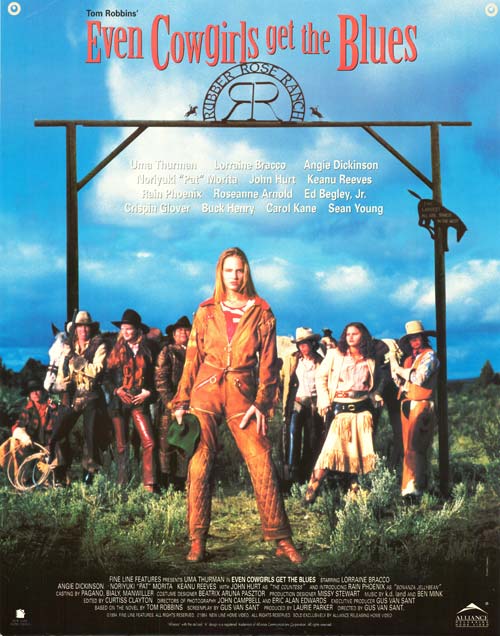

Directed and written by Gus Van Sant

With Uma Thurman, Rain Phoenix, John Hurt, Lorraine Bracco, Noriyuki “Pat” Morita, Angie Dickinson, Sean Young, Keanu Reeves, Crispin Glover, and Carol Kane.

Sissy Hankshaw, born with oversize and decidedly phallic thumbs that inspire her to become a compulsive and virtuoso hitchhiker, never stopping anywhere long enough to pitch a tent, works occasionally as a model for a decadent New York queen known as the Countess, who uses her in feminine-hygiene-spray ads. He wants her to appear in a commercial featuring a flock of whooping cranes that periodically migrate through his dude ranch and beauty salon, the Rubber Ranch, and he sends her there, not realizing that the cowgirls running the place are on the verge of seizing it and turning it into a radical feminist collective with a different set of priorities.

This is the central premise of Tom Robbins’s 1976 hippie novel, though it hardly begins to describe its proliferating characters and issues. For starters, there’s a Mr. Natural sort of guru hiding out in the mountains overlooking the Rubber Ranch — a Japanese American known as the Chink, who periodically has sex with one of the cowgirls, Bonanza Jellybean, and eventually impregnates Sissy, and who maintains a Rube Goldberg sort of timepiece that was bestowed on him by a group of renegade Indians known as the Clock People. There’s also a tender affair that develops between Sissy and Jellybean, not to mention a lot of interest on the part of the federal government in the fate of the whooping cranes, which are periodically fed peyote by another one of the renegade cowgirls, Delores Del Ruby. And there’s an Indian watercolorist named Julian living in New York with whom Sissy has an affair before she heads out west.

Gus Van Sant recut Even Cowgirls Get the Blues at his own expense after audiences were less than enthusiastic at the Venice and Toronto film festivals last fall, and he has certainly improved his loving adaptation of the book. The running time is more or less the same, but the pacing is better and the story line much easier to follow, and the added narration by Robbins himself gives the whole thing a more amiable flow.

As one of the few people who felt more sympathetic than not to the original version, I still have to confess that Van Sant’s fourth feature remains a notch or so below his first (Mala Noche), his second (Drugstore Cowboy), and his third (My Own Private Idaho). But a lesser work by Gus Van Sant is still immensely superior to a major work by roughly 90 percent of the directors working in Hollywood at the moment, so there’s nothing at all disgraceful about what he’s done — and a lot that’s funny and entertaining. Yet how you respond will probably have as much to do with how you feel about the material he’s chosen as with what he’s done with it.

Robbins’s novel was a lot more pleasurable when I read it in the late 70s than when I reread it late last summer. I can think of at least a couple of reasons for this. In the late 70s it was still contemporary — the counterculture Robbins was celebrating and blowing riffs on hadn’t yet dissipated or transformed itself into new-age navel gazing, and younger people hadn’t yet started to wonder whether it was all as much fun as it was cracked up to be. Moreover, it was still possible then to be a male fellow-traveler feminist like Robbins without eliciting disbelief or scorn. (At the press conference for the movie in Toronto one irate questioner asked Robbins how he dared write about women without being a woman, to which he calmly replied, “That’s like saying you have to be a deer in order to write Bambi.”)

Moreover, Robbins’s exuberant, knowledgeable digressions and all-around playful prose, both functions of his bantering white-southern jive, aren’t really suitable for replay to the degree that, say, Thomas Pynchon’s are, because they don’t involve the same sort of formal and conceptual design. The book’s delights are relatively local and momentary — closer to imaginative stand-up routines than to lasting myths or visions. This doesn’t necessarily make them less enjoyable — the novel is still a lively read — but it does make them seem more arch on second reading.

Van Sant has wanted to make a movie out of the novel since the 70s, but by the time he finally had a chance to do it he couldn’t make it contemporary. Yet making it a period piece would clearly betray the contemporary spirit of the original. The solution he hit on — setting the film in its own period, but treating that period as if it were contemporary — has advantages and drawbacks. The main drawback of the original cut was that people unfamiliar with the novel tended to find it incoherent because the period placement wasn’t clear. The main advantage of the newer version is that, thanks to the addition of Nixon’s voice heard over a radio, it’s now clearly set in the mid-70s — though we don’t hear the broadcast until one of the later scenes. Whether it’s read as contemporary or period, a certain sleight of hand is involved.

Given Van Sant’s talent, the problems of adapting this novel don’t concern how much of Robbins’s flavor can be imaginatively translated into a movie, but how much can be translated into a movie Hollywood producers are willing to bankroll. The answer? Not a whole lot, but some. At the Toronto press conference I asked Van Sant whether he had final cut, and he assured me he did. But he added that his wilder original script, which adapted some of Robbins’s goofy interpolated essays along with the plot, was rejected outright by the producers.

In the final analysis, whether you like this movie or not will be largely a function of your expectations. If what you’re looking for are a few slugs of authentic Robbins flavor, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues delivers. But if you’d rather see a brand-new Gus Van Sant fantasia constructed on the bare bones of the novel — closer to my preference — whether you come away satisfied is likely to depend on how you feel about Van Sant’s recasting the original material in less heterosexual and more lesbian terms. Julian (Keanu Reeves) is still around long enough to make a guest appearance, but not long enough to bed down with Sissy (Uma Thurman); the Chink (Noriyuki “Pat” Morita) still lives in a mountain cave and apparently makes it with both Sissy and Jellybean (Rain Phoenix, in a charming debut), but he no longer gets Sissy pregnant, as he did in the first cut. (There’s also less metaphysics; the Clock People and their contraption are nowhere to be seen.) What remains is lucid and digestible on its own terms, though a few loose strands are still apparent: it’s hard to know why Julian puts in an appearance at all, and the Chink is around mainly for comic relief.

In the November 1993 issue of Sight and Sound B. Ruby Rich celebrated the first cut as a potential cult classic, declaring that the shift in sexual orientation is all for the better. It’s easy to see what she means. The reorientation also makes the story feel more contemporary. There’s the additional pleasure of numerous cameos — novelists Ken Kesey (as Sissy’s father) and William S. Burroughs (offering a pithy one-word commentary on New York City), Roseanne Arnold as a fortune-teller, the late River Phoenix (Rain’s brother, to whom the film’s final version is dedicated) as a hippie, and Udo Kier as a TV-commercial director. There’s even time for a few lyrical moments that show Van Sant at his best: one lovely shot of a half-moon speeding past a craggy bluff may be worth the price of admission. But I have to admit I’d rather have Van Sant and Robbins separately. For all the meeting of minds, I’d rather see them roaming more freely on their respective turfs, where each of them has more to say.