From the August 27, 1980 issue of The Soho News — only slightly tweaked almost three decades later. –J.R.

Douglas Sirk in Germany: Four Films

Museum of Modern Art, Aug. 15-18

It must have been in the late spring of 1959 — surrounded mainly be weeping matrons at a matinee of Imitation of Life in Florence, Alabama — that I first tangled with the considerable talents of major melodramatist Douglas Sirk. At the time, these were focused on the task of encouraging white middle-class segregationists and racists to weep bittersweet buckets over the sentimental death of an Aunt Jemima figure named Annie (Juanita Hall), a nas ole cullid lady (as those matrons would have put it) who — unlike her sexy and evil light-skinned, teenage daughter, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) — knew her place, accepted her color as a necessary cross to bear, and then died of a broken heart when Sarah Jane rejected her.

Bearing in mind this particular praxis of Sirk’s last Hollywood film, I’ve always felt just a little querulous when armchair Marxists in London have patiently explained to me that Sirk was actually a Brechtian subversive back in the ’50s, boring from within — subtly and secretly criticizing our American values. Much too subtly and secretly for anyone to know it, I’d argue back. Sirk puts it more cautiously himself: “Imitation of Life is a picture about the situation of the blacks before the time of the slogan `black is beautiful.'” Back in Alabama, this isn’t called Brechtian, it’s called scaredy-cat.

Given such ambivalence about the social meanings of Sirk’s Universal weepies in the ’50s — which is quite separate from the issue of the pleasure and enlightenment we can gain from them today — the Museum of Modern Art’s recent and welcome short season of Sirk’s German features during the Nazi period, comprising four of the seven features he directed for UFA, offered a fascinating side-dish to his Hollywood work. In addition to being a glowing tribute to Sirk’s consummate craftsmanship, it furnished yet another opportunity to wonder why a director like Sirk is so fashionable today — in contrast to, say, the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s, when all his major films were being made.

There’s a curious, unresolved split, at any rate, between the leftist reading of Sirk movies privileged by several English and Continental critics (Jon Halliday, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Paul Willemen among them) and seconded by many American academics, and the boorish, campy interruptions to a brief lecture by programmer Richard Traubner introducing the MOMA season — or trying to, until he was literally driven from the podium. Most of the latter responses seemed to come from impatient Zarah Leander buffs, whose shortsighted emotions seemed to make them spiritual soulmates of those Alabama matrons. It’s a split that makes the German work of Detlef Sierck (as he was known at the time) something of a Rorschach test for contemporary critics and audiences alike.

***

Two of the four films shown featured the legendary Nazi musical star, Zarah Leander — a beautiful Swede who made ten films in Germany (playing a foreigner each time), and briefly became a conscious cross-reference and putative rival to Garbo and Dietrich, until the Allies bombed her German villa. (More recently, she played the Hermione Gingold part in a Viennese production of A Little Night Music.)

Zu Neuen Ufern (To New Shores), which transformed Leander into an overnight sensation in Germany, and La Habanera, an immediate spinoff made and released the same year (1937), are both kitschy star vehicles principally set in exotic locales — Australia and Puerto Rico, respectively. (The former was reportedly shot on location, while the latter was mainly filmed in Spain.)

To New Shores — the more ambitious and less tacky of the two, adapted from a German novel — concerns one Gloria Vane (Leander), an English musical hall singer who takes the rap for her recently departed lover, Sir Albert Finsbury (Willy Birgel), after he forges a check. She is sentenced to seven years in Paramatta Penitentiary in Australia, and an elaborate transition from English trial to Australian prison is effected by a street singer out of Brecht/Weill — one of the many reminders of Sirk’s substantial background as a leftwing stage director in the ’20s and ’30s.

Sir Albert, unaware of all this, has meanwhile gone off to New South Wales himself, and is courting the local governor’s daughter — quite enough to set Sirk’s efficient machinery of pathos and melodrama fully in motion, in a plot whose trimmings (Australia, transferal of guilt, mirrors, suicide) recall some of those of Hitchcock’s 1949 Under Capricorn. This enjoyably escapist movie has been oddly described by the director (in Halliday’s Sirk on Sirk) as “social criticism” that tries “to awaken the audience to a consciousness of conditions”.

He’s clearly referring here to the conditions of Australian prisons for women — a burning issue, I’m sure, in 1937 Nazi Germany (amply illustrated by a musical number in which Leander and other prisoners sing and make baskets in unison like slightly disheveled chorines in a Gold Diggers movie). He can’t be referring to “conditions” that have anything to do with the lives of his paying audience.

La Habanera, the silly spinoff — scripted by Nazi writer Gerhard Menzel, and also described as “social criticism” by Sirk — is pretty racist about weighing the Nordic virtues of the heroine and her son against a large cast of sleazy Latin villains. Yet arguably it may not be much more so than an Esther Williams banana-republic musical of the ’50s might be about its own characters.

A key line of dialogue has the star declare to her Puerto Rican husband-to-be (Don Pedro de Avila, a hand-me-down Cesar Romero), “La Habanera’s to blame! It wasn’t you!” As in To New Shores, the sexy Sternbergian lighting effects, with venetian blinds becoming the equivalent of prison bars — echoed years later in Bertolucci’s The Conformist — seem to be the closest Sirk gets to articulating his own mannerist confinement.

***

I’ve saved Stutzen der Gesellschaft (Pillars of Society, 1935) and Schlussakkord (Final Chord, 1936), respectively the worst and best films of the season, for last. The first, a dull adaptation of Ibsen, is memorable chiefly for its beginning, set in the American West — including a version of “Swanee River” in German, led by a cowboy with a banjo, and a tap-dancing darkie. The second, which I’ve seen twice, seems to me a concerto of dazzling virtuosity — a Sirk film on the level of All That Heaven Allows or The Tarnished Angels.

A studio film par excellence, with lovely sets by Erich Kettelhut (who worked on Metropolis and The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse), Final Chord opens with a rapid montage sequence of dancing legs, glasses of beer and other forms of New Year’s Eve revelry in Manhattan. A drunk spills out into Central Park and comes upon a man on a bench who has just committed suicide. A couple of shock cuts — both anticipating the Mardi Gras of The Tarnished Angels — shows the foot of another drunk heedlessly crushing a party mask on a littered stairway, and a pair of abrasive revelers breaking into the hotel room of the dead man’s young widow.

Sirk has labeled the film a turning point in his career because of its exaltation of “cinema values” over “literary (or stage) values,” and it’s certainly hard to think of another film in his canon that exploits the medium with such reckless pleasure. One finds multiple references to theater (a ballet, an opera, a child’s puppet play and a nightmare that mixes part of the preceding, staged in the heroine’s mind); remarkable uses of match cuts, shadows and subjective camera angles; and a split-screen concept that De Palma might well envy.

There’s also a startling moment of mise en scène that places Lil Dagover’s hand-mirror directly in front of the face of her maid and confidante, which not only dramatizes the erotic undercurrent between these women (a bit of sly Viennese indirection redolent of Stroheim and Preminger), but also conceivably surpasses all the other play with deceitful mirrors that runs obsessively through Sirk’s work.

It’s possible that I’m biased by a certain feeling about the film’s music. That is, it doesn’t sound all that melodramatic or unreasonable to me that a desperate German widow named Hanna (Maria von Tasnady) with some resemblance to Janet Gaynor, sick in bed in Manhattan, could recover the will to live by listening to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, broadcast live from Berlin. But I’m also taken with the supreme economy of the last sequence — using a performance of Handel’s Judas, also conducted by the hero (Willy Birgel) — where the classy clothes worn by Hanna and her son, both listening devotedly in the wings, are enough to establish that she’s married the conductor.

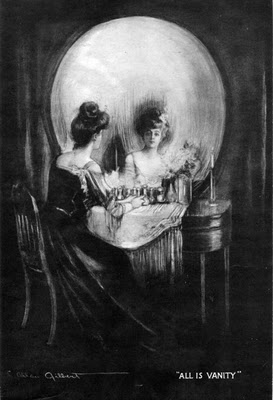

Panning up from this mother-and-child tableau to statues of cherubs with trumpets is a good example of Sirk’s silent sarcasm, which is constantly looking for ways to gently corrode his conventional images into slightly tarnished mirrors. But such talented, ironic duplicity — so evocative of that optical illusion whereby a woman at her dressing table gradually becomes a grinning skull — shouldn’t be confused with “secret” social criticism (whatever that is). It makes more sense to value Sirk’s best movies for their craft and sincerity than for all their carefully hidden bitter almonds, which helped no one in the ’30s or ’50s but Sirk himself.

—The Soho News, August 27, 1980