This essay, reprinted in my 2010 book Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, appeared in French translation in Le Mythe du Director’s cut (Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2008), a collection coedited by Michel Marie and François Thomas and adapted from a lecture I gave at a conference about “directors’ cuts” that was held at the Toulouse Cinémathèque in early 2007. I should add that this was written prior to the release of Blade Runner: The Final Cut, which I subsequently reviewed in the November 1, 2007 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Perhaps the biggest source of confusion regarding the term “director’s cut” is the fact that it can serve both as a legal concept and as an advertising slogan, and both as an aesthetic theory and as an actual aesthetic praxis. In some instances, it can serve all of these functions, but I would argue that most of these instances occur in France —-the only country, to my knowledge, where the legal concept is backed up by an actual law pertaining to les droits d’auteur. And even here, I’ve been told that this law is not always and invariably a guarantee of artistic freedom. A few years ago, while he was working on Le temps retrouvé, Raúl Ruiz told me in effect that in some cases it could function as a law that took on the characteristics of a deceitful advertising slogan—-which is to say, that it doesn’t always function as an enforceable law, especially when larger sums of money are involved and various kinds of coercion are available to producers who want to impose their will on certain creative decisions made by filmmakers.

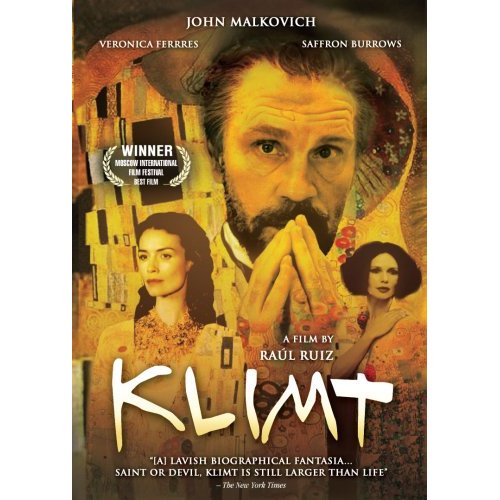

Even in the case of Ruiz’s more recent Klimt, where the term “director’s cut” still has a real meaning, it has apparently only been in France that the director’s cut is being shown commercially. At the Rotterdam film festival last year, both the director’s cut (which runs 127 minutes) and the producer’s cut (which runs 97 minutes) were shown on separate days. I saw both versions and found that the producer’s cut paradoxically and ironically seems to last much longer, to the point of tedium, because it comes across as a failed biopic whereas the director’s cut, which clearly doesn’t aspire to the status of a biopic, seems not only shorter but also more successful in terms of being more artistically coherent.

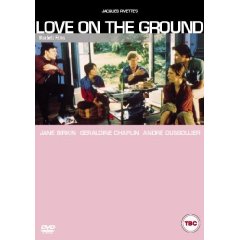

I should add that this state of affairs is quite common; I would also say that Jacques Rivette’s original 169-minute version of L’amour par terre (1983) feels shorter than the 125-minute version that he was asked by his producer to edit — which is the only version that was commercially available until the 169-minute was belatedly released on France on a DVD box set 20 years later. I would also argue that the longer version is more interesting, more coherent, and even more commercial — which is always or almost always the case with Rivette, especially if we recall that in 1968 the long version of L’amour fou performed better at the box office.

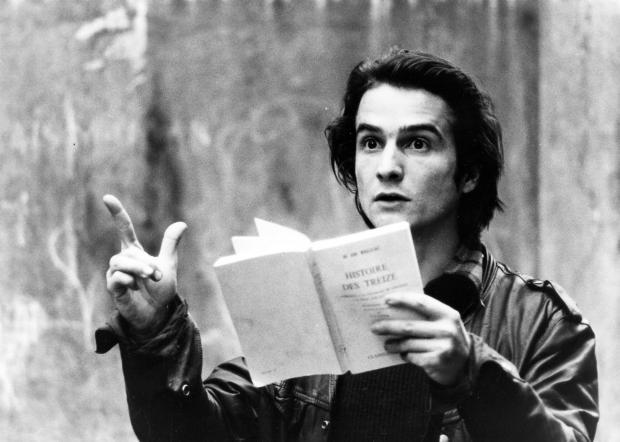

The case of Out 1 is more debatable, of course—and less directly relevant to the concerns of this discussion, because both versions qualify as director’s cuts: the 760-minute film of 1971 in eight episodes, made for (but rejected by) French state television, where Rivette hoped it would be run as a serial, and the radically different 255-minute version that he prepared in 1972, with a separate editor, for theatrical showings. But the issue of “longer” versus “shorter” remains pertinent to the more difficult task of discriminating between two or more director’s cuts of the same material– which is surely an issue worth addressing, and one that challenges our usual terminology and categories. Are Out 1 and Out 1: Spectre two different films, or two different versions of the same film? If we decide they’re different films, our task becomes relatively easy. But if we decide that they’re two different versions of the same film, don’t we then have to construct, at least implicitly, a theoretical or Platonic model of this “same film” that necessarily qualifies as a third version? And don’t we then have to judge the two versions according to how close each one comes to this model?

In order to make a distinction between aesthetic and business ways of dealing with this issue, it seems worth arguing that the long version of Out 1 was never given an opportunity to function in commercial terms once it was rejected by French television —-or at least it wasn’t until it finally surfaced on cable television many years afterwards, in the early 1990s, long after its historical moment had passed. And because the serial is easier to follow as narrative and, as Rivette himself has noted, closer to being a comedy than the four-hour version, I believe it can also be deemed more commercial. Yet paradoxically, Spectre was created precisely in order to make Out 1 more presentable—-that is to say, more commercial.

As a final, preliminary comment on the sort of ongoing confusion that we typically encounter between aesthetics and business, let me cite a joke offered in 1971 by the screenwriter and director of Westerns Burt Kennedy, as cited by Richard Corliss in his 1974 book Talking Pictures: “I was driving by Otto Preminger’s house last night—-or is it [better to call this] `a house by Otto Preminger’?”

Arguably, one reason why the film industry as a whole has encouraged and promoted the concept of a director’s cut, even though it might appear to be counter to its own interests in certain cases, is that it enables a film’s owner to sell the same product to the same customer twice. The mythology underlying this process appears superficially to be that every film has two versions, a correct one and an incorrect one. But in fact this isn’t quite true. A better paraphrase of the mythology would be to say, more paradoxically, that every film has at least two versions — a correct one and a more correct one.

I should add that in François Thomas’s French translation of the previous two sentences, in my abstract for this paper, which I approved last month, this particular distinction became somewhat simplified: “Superficiellement, le mythe à l’œuvre est que chaque film a deux versions, une bonne et une mauvaise. En réalité, il sous-entend que chaque film a au moins deux versions, une bonne et une meilleure.” On reflection, this is a journalistic simplification—-and a necessary one, I should add, for the purposes of a brief abstract, but still inadequate in relation to the larger point I wish to make. The distinction seems worth making, because the term “more correct” in English is a barbarism—-a little bit like the term “slightly pregnant”—-and I used it to parody the sort of illogical leap sometimes made by large companies when they employ the term “director’s cut”.

As one example of what I mean, I’d like to quote my capsule review of something that’s widely known as the “director’s cut” of Joseph Losey’s Eva (or Eve, as it’s known in the U.K.) — a review written a few years ago for the Chicago Reader:

“A failure, but an endlessly fascinating one. Between making his only SF film (The Damned) and his first successful art movie (The Servant), blacklisted expatriate Joseph Losey directed this 1962 film, adapted by Hugo Butler and Evan Jones from a James Hadley Chase novel, about a washed-up Welsh novelist of working-class origins (Stanley Baker) who unsuccessfully pursues a high-class hooker (Jeanne Moreau) while effectively driving his wife (Virna Lisi) to suicide. The film is pretentious and plainly derivative; I’ve always regarded as unwarranted and philistine Pauline Kael’s ridicule of Antonioni, Resnais, and Fellini in an article of the period called “The Come-Dressed-as-the-Sick-Soul -of-Europe Parties,” but she might well have included Losey’s film, with its clear debt to all three. It’s a painful testament of sorts (Losey himself can be glimpsed in a bar during a pan that also introduces the hero, showing his personal stake in the proceedings from the outset), though it makes wonderful use of locations in Venice and Rome and features an excellent jazz score by Michel Legrand (with a pivotal use of three Billie Holiday cuts). A decadent period piece and a sadomasochistic view of sexual relations, this singular, resonant, and at times even inspiring mannerist mess is far more interesting than a good many modest successes. Losey can’t be blamed entirely for the film’s disjointedness either; its producers mucked around with it, ultimately reducing it from 155 to 100 minutes. Labeling this rare 120-minute version with two kinds of Scandinavian subtitles — the longest surviving edition since the 60s — the `director’s cut,’ as various publicists and reviewers have been irresponsibly doing, only adds insult to injury.”

This review places the blame for misappropriating the term “director’s cut” on “various publicists and reviewers,” which is a way of personalizing the issue. But more objectively, I believe one could place at least part of the blame on advertising and journalism as institutions, both of which commonly feel obliged to represent both the meaning and the value of certain films in “25 words or less,” as the common expression goes. In other words, one can’t simply blame publicists and reviewers for these abuses when the individuals in question are merely responding to the requests and perceived requirements of studio executives and newspaper and magazine editors. All these figures tend to regard both films and film reviews as commodities rather than as unique objects, with the consequence that many possible distinctions can get bypassed for the sake of what might be described as an “undisturbed” and continuous product flow. Nuances and ambiguities tend to get overlooked whenever considerations about the flow become more important than anything else.

One good example of what I mean is the 2004 version of Samuel Fuller’s The Big Red One produced by Richard Schickel. To my mind, neither the 1980 release nor Schickel’s alleged “reconstruction” of the original longer cut of the film qualifies as a director’s cut. For one thing, Fuller was adamant about not wanting an offscreen narration, and an offscreen narration figures in both of the existing versions. If I had to choose between these two versions, I would choose the more recent one, although this isn’t the same thing as calling it the director’s cut. But in the kind of journalistic shorthand that we’ve become accustomed to, it automatically takes on the status of one.

On the other hand, we face a quite different dilemma when we encounter two of more versions of a film that do qualify as director’s cuts. Consider the principal Italian version of Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry — which is missing the film’s final sequence, a documentary sequence shot in video, that occurs in all the other versions of the film that I’m aware of. (Reportedly this sequence was shot by Kiarostami’s son for a documentary about the making of Taste of Cherry, and Kiarostami’s decision to include it was an afterthought.)

Soon after the film premiered at Cannes in 1997, many critics and various friends and acquaintances of Kiarostami urged him to cut the original ending, for commercial and/or artistic reasons. Half a year later, when I heard that Kiarostami himself decided to delete this ending from the version of the film opening in Italy, I was so upset and appalled by this decision that I wrote Kiarostami a letter and faxed it to him in Iran, urging him to reconsider this decision. At this point, I should add, the film had not yet opened commercially in the U.S., and I was especially worried about the film being deprived of its original ending elsewhere, especially because I regarded this ending then—-and continue to regard it today—-as a major asset of the film, not in any way a flaw. Although I didn’t mention this in my letter, I believed that the changes in style and form represented by the final scene were comparable in some ways to the changes in the final sequence of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Eclisse, which was reportedly cut from the film, and completely without the consent of Antonioni, when it showed at certain American cinemas in the early 60s, as reported at the time by the critic Dwight Macdonald in Esquire — a decision apparently made by certain exhibitors. In the case of L’eclisse, it appears that the stated reason for removing this sequence was the fact that neither of the two stars, Monica Vitti and Alain Delon, appears in it, though of course this absence is part of the point of the sequence. In the case of the ending of Taste of Cherry, the actor playing the major character appears in it, but as himself, not as his character, and Kiarostami appears in the sequence as well; the point in this case is to reflect on the shooting of the film rather than on its fictional story. It’s obvious in these two cases that without their final sequences, both films are quite different, and to my mind they’re also quite inferior.

I was both surprised and gratified when Kiarostami wrote me back in English only two days later. He explained to me that for the Italian-dubbed version of the film, he decided, as an experiment, to show the film with the original ending in some theaters and without the original ending in some other theaters, and to see what the differences in audience reactions would be. In other words, one could conclude from his letter that there were in fact two director’s cuts of Taste of Cherry in Italy, with and without the original ending, but that he intended to show the film with the original ending everywhere else, which suggested that the original version was the one that he still preferred. From this standpoint, the notion of “une bonne version et une meilleure version” continues to have some meaning, but not “une version exact et une version plus exact”.

Unfortunately, as far as I could tell, on the basis of the testimonies of various Italian friends, Kiarostami’s experiment lasted only as long as his stay in Italy; after he left, the Italian distributor chose to show only the shorter version of the film, and the longer version basically disappeared. This raises the interesting and somewhat vexing question of whether or not the shorter director’s cut of Taste of Cherry was still the director’s cut after Kiarostami left Italy.

An important point arising from this example is that any director’s cut has to be pinpointed in time for this label to have any meaning. To postulate that only one director’s cut can exist for a given film implies the privileging of a particular point of closure in the filmmaker’s creative decisions—-a privileging that becomes quite arbitrary in some cases. Since there are many different subtitled versions of some of the later Straub-Huillet films employing different takes and therefore different editing, choosing one version over all the others may be capricious, and arguably the same thing might be true for the separate 1952 and 1953 versions of Othello edited by Orson Welles, as recently described by François Thomas in Cinéma 012, in an ongoing series of articles significantly titled, “Un film d’Orson Welles en cache un autre”. In this case, do we privilege the first thoughts or the second thoughts, and how do we defend our selection?

Once revision becomes an issue, any notion of a single director’s cut has to be discarded. (The same considerations apply, of course, to revisions of literary works by their authors after their initial publication.) And how we evaluate the status of multiple director’s cuts of the same film varies from case to case. To cite a rather extreme theoretical example, I’d like to quote something from Krzysztof Kieślowski regarding his original plans for La Double Vie de Véronique:

“At one stage we had the idea of making as many versions of Véronique as there are cinemas in which the film was to be shown. In Paris, for example, the film was to be shown in seventeen cinemas. So we had the idea to make seventeen different versions. It would be quite expensive, of course-—especially at the last stage of production—making internegatives, individual re-recordings and so on. But we had very precise ideas for all these versions. What’s a film? we thought. Theoretically it’s something which goes through a projector at the speed of twenty-four frames a second and, in fact, the success of cinematography depends on repetition. That is, whether you project in a huge cinema in Paris or in a tiny cinema in Mława or a medium-sized cinema in Nebraska, the same thing appears on screen because the film passes through the projector at the same speed. And so we thought, Why, in fact, does it have to be like that? Why can’t we say that the film is hand-made? And that every version’s going to be different? And that if you see version number 00241b then it’ll be a bit different from 00243c. Maybe it’ll have a slightly different ending, or maybe one scene will be a tiny bit longer and another a bit shorter, or maybe there’ll be a scene which isn’t in the other version, and so on. That’s how we worked it out. And that’s how the script was written. We shot enough material to make these versions possible. It would be possible to release this film with the concept that it was, so to speak, hand-made. That if you go to a different cinema, you’ll see the same film but in a slightly different version, and if you go to yet another cinema, you’ll see yet another version, seemingly the same film but a little different. Maybe it’ll have a happier ending, or maybe slightly sadder—that’s the chance you take. Anyway, the possibility was there. But as always, of course, it turned out that production absolutely didn’t have the time, and that, in fact, there wasn’t any money for it either. Perhaps the money was less important. The main problem was time. There wasn’t any time left.” (1)

Kieślowski went on to explain that there was in fact two versions of the film because he made a different version of the film’s ending for America. In fact, although he didn’t say this, the separate, “happier,” and somewhat less ambiguous ending he edited for the U.S., which was four shots longer, was done at the request (or perhaps at the demand) of Miramax’s codirector at the time, Harvey Weinstein, after the film showed with its original ending at the New York Film Festival in 1991 and Miramax had agreed to distribute the film. According to an article by Weinstein which I read years ago, and which I don’t have access to now, Kieślowski congratulated Weinstein on the brilliance of his suggestion and said that it was better than his own original ending. According to Kieślowski himself, however, his thoughts about the matter were somewhat different and more cynical: “Of course I thought about the audience all the time while making Véronique so that I even made a different ending for the Americans, because I thought you have to meet them halfway, even if it means renouncing your own point of view.” (2)

The difference between Weinstein and Kieślowski’saccounts seems crucial. According to Weinstein—-whose article was clearly an explanation of why he was so brilliant that he could only improve other people’s films by re-editing them, which he then proceeded to do with a large number of his subsequent releases, with or without the director’s approval—-the “true” director’s cut of Véronique would be the U.S. version, precisely because he knew or understood Kieślowski’s intentions better than the filmmaker did himself. (This is the same argument that was recently made to me by Michael Dawson — an American film technician who has already revised the soundtrack of Welles’s Othello and plans to revise the soundtrack of Chimes at Midnight in the near future by adding the sound of neighing horses to one shot “because if Orson were alive today, I’m sure he would have done it himself.”) According to Kieślowski —- and, I’m happy to report, according also to Criterion, who just released the film on DVD — the director’s cut is the original one released everywhere except for the U.S., so that the American ending on the Criterion DVD is included simply as a bonus. But it’s important to add that this distinction can be made only if we limit Kieślowski to one director’s cut; if he’d produced seventeen director’s cuts, as originally planned, the issue would be much harder to resolve.

Let me cite a more specific example of revision in the case of a film on which I worked myself—-the only time in my life when I’ve ever been employed by a film studio. This was on the re-editing of Welles’ Touch of Evil by Walter Murch according to a studio memo written by Welles while the film was in its penultimate stages of postproduction—-a project undertaken by producer Rick Schmidlin, on which I was hired to serve as a consultant. I was brought to this job by the fact that I’d originally published about two-thirds of this memo myself, in the fall of 1992, almost simultaneously in Film Quarterly in the U.S. and Trafic in France. I was editing the book This is Orson Welles at the time, published in France as Moi, Orson Welles, which chiefly consisted of a lengthy interview with Welles by Peter Bogdanovich, but also contained many documents, including an edited version of this memo by Welles, at least until my editor decided to delete this text for reasons of space. So I decided to publish the text elsewhere, as what might be described as an “outtake” from the book, and after having been turned down by both the American Premiere and Film Comment, this text was accepted by Film Quarterly and Trafic. (Today, the full text of this memo is available only on the Universal DVD of this re-edited version of Touch of Evil—-the only version it has bothered to release so far—-and on the web site Wellesnet.)

Some years later, the cinematographer Allen Daviau contacted me about possibly using this text in some fashion on the laserdisc of Touch of Evil that was then being planned, and still later this project was taken over by Rick Schmidlin, who then approached Universal with the proposal of following the instructions in the memo as closely as possible in a re-edited and remixed version of the film. It was clear to Schmidlin, Murch, and myself throughout this project that what we were undertaking was neither a “restoration” nor a “director’s cut”, and we went to great lengths to stress this fact in the pressbook that we prepared. One can’t restore something that never existed previously, and nothing survives in Universal’s Touch of Evil materials that qualifies as a “director’s cut”. Welles’s own comments in the memo are unambiguous and unequivocal in this respect. To quote from two separate passages:

“My effort has been to keep scrupulous care that this memo should avoid those wide and sweeping denunciations of your new material to which my own position naturally and sorely tempts me. In this one instance I’m passing on to you a reaction based – not on my convictions as to what my picture ought to be – but only what here strikes me as significantly mistaken in your picture. It’s sufficiently your own by now, for me to be able to judge it on what I take to be your terms alone, and to bring to that judgment – (after so much time away from the film in any form) – a certain freshness of eye.”

And later on: “I ask you please to believe that what minimum criticism of that new material I am passing on to you, is made in recognition and full acceptance of the fact that the final shape and emphasis of the film is to be wholly yours. I want the picture to be as effective as possible – and now, of course, that means effective in your terms.”

Furthermore, it was never the intention of Schmidlin, Murch, or myself to supplant the earlier versions of Touch of Evil that had already circulated. We hoped, in fact, that a box set devoted to at least three versions would be released by Universal; and the fact that this hasn’t yet happened, and may never happen (3), can perhaps be attributed to the lack of knowledge about our work on the part of both Beatrice Welles, Welles’s youngest daughter, and Universal, who jointly determined the nature of the DVD release, without any participation from Schmidlin, Murch, or myself. Speaking now only for myself, I would use the same term to describe what we did as the term used by Kiarostami: “experiment”, which might have also been used by Kieślowski if he had edited seventeen separate versions of Véronique. But, as in the case of Kiarostami, our power to influence the reception of this experiment was limited to a period when we were still in some control over how it was being understood. Although we were happy to find that a large number of the original reviews of the re-edited Touch of Evil took some trouble to differentiate what we had done from a restoration or a director’s cut, thanks to our efforts, this emphasis essentially vanished over time, so that many of the supposedly authoritative reference books such as Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies misrepresent our efforts by reverting to those terms, which, to all practical purposes have now become trade terms rather than aesthetic or material descriptions of our work.

Commodification of artworks ultimately affects not only their definitions and catalog descriptions but also to some extent their distribution. As astonishing as this may sound, all original invitations from foreign film festivals to show the re-edited Touch of Evil were rejected by the woman in charge of foreign sales at Universal because, according to Rick Schmidlin, she was convinced that no one outside the United States had the least bit of interest in Orson Welles. Once she changed her mind, the film was of course shown all over the world, but arriving at this stage took some time.

More generally, the issue of commodification can sometimes affect the coordination between the technical realization of a DVD and its content. By chance, while writing this lecture I received in the mail a few DVDs from Australia containing commentaries by the Australian film critic Adrian Martin. One of these films was Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, and as many of you will recall, less than five minutes into the film, Buñuel deliberately repeats a brief scene of guests arriving at a dinner party at the same time that a couple of servants are leaving and the host is calling for his butler, showing this scene a second time from different camera angles. Martin’s commentary deals at some length with this repetition and its significance — quoting Buñuel’s own comments in Mon dernier soupir about several deliberate repetitions in the film, including this one, and how this one was even misunderstood by Buñuel’s chief cameraman while the film was being edited, believing it to be a technical error even though this cameraman had shot both versions of the scene himself.

But through an absurd technical error on the part of the DVD company, which ignored Martin’s commentary and arrived at the same erroneous conclusion as the cameraman, the scene’s repetition was deleted — even though Martin, who was watching a more complete print while giving his commentary, discusses it at some length. So ironically, it might be concluded that one Surrealist nonsequitur, quite deliberate, was replaced by another one, completely accidental, to anyone following Martin’s commentary. In both cases, the viewer is apt to be puzzled by and perhaps a little incredulous about what he has just seen and heard.

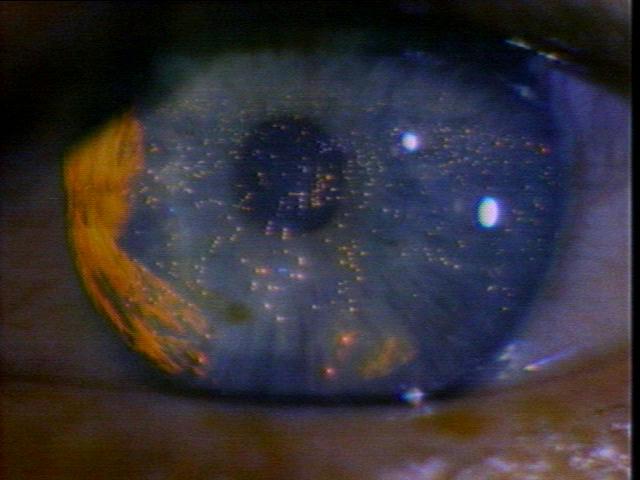

I’d like to conclude by broaching a few of the ontological issues raised by the two best known versions of Blade Runner—-namely, the original release version of 1982 and the so-called director’s cut of 1992. To complicate matters, the DVD of the latter version is explicitly labeled “The Director’s Cut: The Original Cut of the Futuristic Adventure”. But as we know from Paul M. Sammon’s book Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), none of the five separate versions of Blade Runner seen by the general public fit that description. On the other hand, one can certainly sympathize with the dilemma of a publicist who might have wished to represent accurately the nature and status of any of these five versions on a DVD box label—-a list which doesn’t even include what Sammon calls “Paul Gardiner’s Blade Runner: The Final Director’s Cut,” a sixth version that hasn’t yet been shown to the public, and which is even less of a director’s cut than at least two of the others.

What follows is a highly abbreviated account of a slapstick saga that Sammon devotes an entire book to recounting, and one which for me raises the same question raised by the woman in charge of foreign sales at Universal Pictures —- namely, how the Hollywood studios manage to produce and distribute films at all, much less do so profitably. In 1989, a sound reconstruction consultant named Michael Arick discovered a 70mm print of Blade Runner in a vault. Eventually screened as part of a film series in Los Angeles the following year, this version turned out to be a work print that had been shown as a sneak preview in Denver, Colorado on March 5, 1982 (which is incidentally the same day on which Philip K. Dick’s body was cremated in Santa Ana, California) and then on the following evening in Dallas, Texas. At this point the film had neither a voiceover (apart from one brief segment) nor a happy ending, and the somewhat mixed audience responses persuaded Warners to add both these things. But it’s important to add that the whole idea of using a voiceover had been hatched in mid-1980, after the project had been in development for about five years. According to Hampton Fancher, the main screenwriter, Ridley Scott, the director, “was the one who initially pushed the voiceover idea. That’s why it’s on so many of my drafts”—-and Sammon adds that ample documentation exists to support this statement. But according to David Peoples, Fancher’s cowriter, most of the voiceovers had been removed from successive drafts of the script in early 1981, with the original intention of restoring some of them in postproduction. And in fact, Harrison Ford recorded a voiceover three separate times—-the first two times in late 1981, supervised by Scott, who subsequently decided, once again, to scrap almost all of it in either version, and the third time, after the Denver and Dallas previews, supervised by Bud Yorkin and mainly written by Roland Kibbee, after Scott had essentially given up on his own version.

If we flash-forward again to 1990, when the 70mm preview version was shown, Scott saw it and felt it was closer to his intentions than the 1982 release version. With this in mind, he proposed that Warners release a cleaned-up version of this work print as a director’s cut. But he was too busy at the time working on Thelma and Louise to supervise this work himself—-although a few months later, when he was less busy, he did try, without any success, to purchase the print from Warners. But by this time, Warners had begun to screen the 70mm print publicly more often in Los Angeles, with much success. Then Warners struck a 35mm reduction dupe print from it and opened it commercially in Los Angeles, billed as “The Original Director’s Version”.

Scott, who was back in London at the time, casting his film 1492, wasn’t even aware of this until someone belatedly informed him, in September 1991. He flew back to Warners in Los Angeles and proposed revising this version in order to make it a proper director’s cut. They reached an agreement to proceed with this plan. But due to some misunderstanding and confusion, two different versions of this revision were then set in motion—-one in London, carried out by Michael Arick, who followed Scott’s detailed instructions, and the other one in Los Angeles, carried out by Peter Gardiner, who had a much more rudimentary revision in mind and was apparently unaware that Arick’s version was also in the works. Scott, however, was so distracted by his work on 1492 that he wound up approving Gardiner’s version instead of Arick’s. Neither version, however, had the enigmatic shot of a unicorn which had been deleted during postproduction—-an idée fixe of Scott’s that was far more important to him than any other detail, and a shot that had subsequently been lost by the studio. So when Warners decided to release Gardiner’s aforementioned Blade Runner: The Final Director’s Cut, the sixth version cited by Sammon, without this shot, Scott threatened to place an ad in Variety and Hollywood Reporter publicly disowning this version.

Consequently, Arick was brought back and asked to prepare a third version of the director’s cut in a month’s time—-ignoring most of Scott’s former specifications, but omitting the happy ending and all of the voiceover and somehow contriving to include the shot of the unicorn. Arick finally found an outtake of the unicorn that Scott had rejected a decade earlier, completing his version in the nick of time. And this is the “director’s cut” that we have.

As Arick put it to Sammon later, “I had to resign myself to coming up with a Director’s Cut that was only a slightly modified version of the original theatrical release. But it was better than nothing.” And Scott essentially agreed with this description: “The so-called Director’s Cut isn’t, really. But it’s close. And at least I got my unicorn.”

Scott’s philosophical acceptance of this version as “close” significantly resembles the usual position of publicists regarding such matters — which is that in the final analysis, chaque film a deux versions, une version correcte et une version plus correcte. The notion that any version might be incorrect is one that belongs to history and aesthetics, but not to business.

To add a brief critical afterword to this account, I should confess that, as in the case of George Cukor’s A Star is Born — released in 1954, cut by Warners, and then partially restored in 1983, sometimes with stills to represent missing scenes — I mainly prefer the original release version to the later version that attempts to bring the work closer to its original conception. But I should add that the strength of Blade Runner in either version is more one of spectacle than one of narrative, and more a matter of visual design than one of narrative fluidity or cogency. I find the narrative periodically obscure in both versions, and the additional ambiguity of the second version is not one for me that necessarily enhances the story’s ambiguities about which characters are human and what the characteristics of being human are. I would further argue that the commercial failure of the original release version can probably be blamed in part on the absurdities of the preview system itself — which I have written about elsewhere (4) as a kind of voodoo pseudo-science that relies on an audience forming its impressions and opinions immediately, as soon as a screening is over. Therefore, much of the debate about the relative merits of one version of the film over another is in part a displaced rationalization of a film that is relatively strong as spectacle and somewhat confused and unformed as narrative in all its versions.

Notes

1.Kieślowski on Kieślowski, edited by Danusia Stok, London/Boston: Faber and Faber, 1993, pp. 187-188.

2.Ibid., p. 189.

3.Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See, Chicago: A Cappella, 2000. (See especially pp. 2-9.) August 7, 2008 postscript: I can happily report that my pessimism was unwarranted: a three-disc edition of Touch of Evil is finally being released by Universal in about two months.