From the Chicago Reader (May 18, 2007). I’m reposting this now to celebrate its restoration and revival at Cannes this week, which will hopefully lead to it belatedly coming out on Blu-Ray and/or DVD.

Rightly described by Dave Kehr as Jacques Rivette’s “breakthrough film, the first of his features to employ extreme length (252 minutes), a high degree of improvisation, and a formal contrast between film and theater,” this rarely screened 1968 masterpiece is one of the great French films of its era. It centers on rehearsals for a production of Racine’s Andromaque and the doomed yet passionate relationship between the director (Jean-Pierre Kalfon) and his actress wife (Bulle Ogier, in her finest performance), who leaves the production at the start of the film and then festers in paranoid isolation. The rehearsals, filmed by Rivette (in 35-millimeter) and TV documentarist Andre S. Labarthe (in 16), are real, and the relationship between Kalfon and Ogier is fictional, but this only begins to describe the powerful interfacing of life and art that takes place over the film’s hypnotic, epic unfolding; watching this is a life experience as much as a film experience. In French with subtitles. Sat 5/19, 3 PM, and Thu 5/24, 6 PM, Gene Siskel Film Center. Read more

Members of a farming family incessantly repeat the same lines of dialogue while a student prepares to leave home for school; guests at an interminable wedding cackle maniacally while the ghost of the groom’s lover interferes with the ceremony. Now over 70, the great Russian filmmaker Kira Muratova (The Asthenic Syndrome) seems to get wilder and more transgressive with every passing year. This updated merging of two early Anton Chekhov texts (the short play Tatiana Repina and the story Difficult Natures) veers closer to the mad lucidity of Gogol than to the wry realism of The Cherry Orchard. I found the extreme stylization mesmerizing, hilarious, and ultimately closer to hyperrealism than absurdism, though if you enter this without any warning you might wind up fleeing in terror. In Russian with subtitles. 120 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 19, 1992). There’s a new DVD box set devoted to five Berliner documentaries, including this one, that’s recently come out. — J.R.

INTIMATE STRANGER

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Alan Berliner.

The subject of Alan Berliner’s remarkable hour-long documentary, showing Friday night at Chicago Filmmakers, is his maternal grandfather, Joseph Cassuto — a Jew born in Palestine in 1905 and raised in Egypt, where he started working for the Japanese Cotton Trading Company in his teens. He moved his family to Brooklyn in 1941, shortly before Pearl Harbor, and after the war spent nearly all his time — roughly 11 months out of every year — in Japan, until late 1956, when he transferred to the New York office. He died in 1974.

Considering Cassuto’s globe-trotting, it’s hard to imagine most Americans being interested in Intimate Stranger. It’s taken the better part of a year for it to reach Chicago, after premiering last fall at the New York film festival. After all, this is a country so uninterested in the rest of the world that the foreign policies of its presidential candidates barely seem to matter — and when they do matter, you can bet it’s the welfare of this country rather than the planet that’s at issue. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 23, 1992). — J.R.

Apart from his final feature, Salo, this is probably Pier Paolo Pasolini’s most controversial film, and to my mind one of his very best, though it has the sort of audacity and extremeness that sends some American audiences into gales of derisive, self-protective laughter. The title is Italian for “theorem,” in this case a mythological figure: an attractive young man (Terence Stamp) who visits the home of a Milanese industrialist and proceeds to seduce every member of the household — father (Massimo Girotti), mother (Silvana Mangano), daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), son (Andés José Cruz Soublette), and maid (Laura Betti). Then he leaves, and everyone in the household undergoes cataclysmic changes. Pasolini wrote a parallel novel of the same title, part of it in verse, while making this film; neither work is, strictly speaking, an adaptation of the other, but a recasting of the same elements, and the stark poetry of both is like a triple-distilled version of Pasolini’s view of the world–a view in which Marxism, Christianity, and homosexuality are forced into mutual and scandalous confrontations. Like Pasolini at his best, this is an “impossible” work: tragic, lyrical, outrageous, indigestible, deeply felt, and wholly sincere (1968). Read more

According to Wikipedia, this English-America MGM release about an American teenager (Elizabeth Taylor at 17 playing someone a year older) falling in love with and marrying a 40ish British officer (Robert Taylor) whom she belatedly discovers is a Communist spy — effectively directed by Victor Saville, and recently shown on TCM — lost the studio over $800,000, but it doesn’t say or suggest why. I would guess that this was because, intentionally or not, the film manages to persuade us to identify with the tormented middle-aged spy more than with the tormented patriotic heroine. This isn’t a matter of ideology but a function of how the story gets told. The screenplay by Sally Benson (whose stories provided the basis for MGM’s Meet Me in St. Louis) focuses more on the inner conflicts and secret meetings of the spy than those of the callow girl that he falls for and marries, and the fact that the movie literally ends with her agreeing to lie to everyone about her husband’s suicide to support her own country makes his own deceits seem less reprehensible. It’s a funny paradox that a rabid right-winger like Robert Taylor should make us care so much for a Communist spy, but he does. Read more

From the August 28, 1992 Chicago Reader; reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. — J.R.

THE PANAMA DECEPTION

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Barbara Trent

Written by David Kasper

Narrated by Elizabeth Montgomery.

DEEP COVER

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bill Duke

Written by Henry Bean and Michael Tolkin

With Larry Fishburne, Jeff Goldblum, Victoria Dillard, Charles Martin Smith, Sydney Lassick, Clarence Williams III, Gregory Sierra, and Roger Guenveur Smith.

I wonder how many people under 35 know that one of the most frequent taunts hurled at President Lyndon Baines Johnson during antiwar demonstrations at the height of the Vietnam war was, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Johnson did considerably more than any other U.S. president of this century to turn the civil rights movement into law — even going so far as to appropriate the movement’s theme song, “We Shall Overcome,” for a speech to Congress. But because of his behavior regarding nonwhites overseas, especially in Southeast Asia, a considerable part of the youth of the late 60s regarded him as a mass murderer, and told him so on every possible occasion. It seems plausible that Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection in 1968, announced only four days before Martin Luther King was assassinated, had more than a little to do with the repeated sting of that relentless chant. Read more

In “Being Orson Welles,” Melena Ryzik’s January 15 interview with Christian McKay in “The Carpetbaggers” (“The Awards Season Blog at the New York Times”), she has McKay say the following: “I love the fact that he was as labyrinthine as one of his greatest creations, Caine, but I think he had a much warmer heart.”

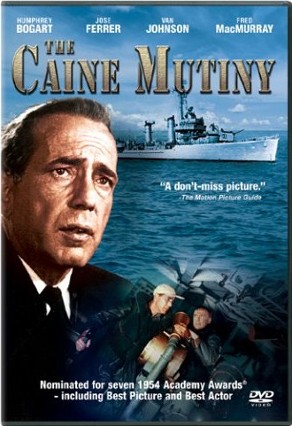

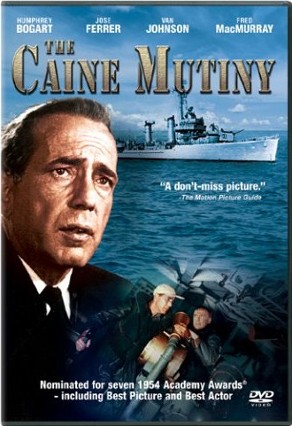

Elsewhere she wonders why McKay hasn’t received more award nominations for his performance in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles. But if even his interviewer can’t tell the difference between Caine and Kane, maybe she shouldn’t be so surprised. (If she’s thinking of The Caine Mutiny, the most “labyrinthine” character is probably Lieutenant Commander Philip Francis Queeg, played by Humphrey Bogart in the film; Caine is the name of his ship, and Welles doesn’t appear in that movie at all.) [1/16/10] 1/17 postscript: this finally got corrected two days later.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 1, 1995). — J.R.

My favorite Douglas Sirk film — made in Germany in 1936, when he was still known as Detlef Sierck — is a dazzlingly cinematic, fast-moving melodrama built around classical music; it’s alternately perverse, exalted, and delirious. Shuttling back and forth between New York and Berlin with an ease that suggests those cities were in closer proximity to each other in the 30s than they are today, the opening sequences present a destitute widow (Maria von Tasnady) recovering her will to live by listening to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy on the radio, broadcast live from Germany, where the conductor (Willy Birgel) is coincidentally in the process of adopting her little boy. When she returns to Berlin she goes to work as the boy’s nanny, concealing the fact that she’s his mother, while the conductor’s less musically inclined wife (Lil Dagover) tries to break free from an astrologer-blackmailer who’s threatening to expose her adultery with him. There’s also a creepy and seemingly malevolent maid, a climactic trial, and several sequences involving music and duplicity that produce some astonishing visual candenzas and editing rhyme effects. (This is the film that inspired Sirk to note that camera angles are a director’s thoughts and lighting is his philosophy.) Read more

From the August 27, 1980 issue of The Soho News — only slightly tweaked almost three decades later. –J.R.

Douglas Sirk in Germany: Four Films

Museum of Modern Art, Aug. 15-18

It must have been in the late spring of 1959 — surrounded mainly be weeping matrons at a matinee of Imitation of Life in Florence, Alabama — that I first tangled with the considerable talents of major melodramatist Douglas Sirk. At the time, these were focused on the task of encouraging white middle-class segregationists and racists to weep bittersweet buckets over the sentimental death of an Aunt Jemima figure named Annie (Juanita Hall), a nas ole cullid lady (as those matrons would have put it) who — unlike her sexy and evil light-skinned, teenage daughter, Sarah Jane (Susan Kohner) — knew her place, accepted her color as a necessary cross to bear, and then died of a broken heart when Sarah Jane rejected her.

Bearing in mind this particular praxis of Sirk’s last Hollywood film, I’ve always felt just a little querulous when armchair Marxists in London have patiently explained to me that Sirk was actually a Brechtian subversive back in the ’50s, boring from within — subtly and secretly criticizing our American values. Read more

From the August 18, 1989 Chicago Reader; this piece is also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

DISTANT VOICES, STILL LIVES

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Terence Davies

With Freda Dowie, Pete Postlethwaite, Angela Walsh, Dean Williams, Lorraine Ashbourne, Debi Jones, Michael Starke, and Vincent Maguire.

An autobiographical film about growing up in a Catholic working-class family in Liverpool in the 40s and 50s. Achronological glimpses of a traumatic family life, with particular emphasis on a funeral and two weddings. A collection of radio shows and nostalgic songs sung at parties and pub gatherings. A highly condensed, triple-distilled family album of faces and feelings organized around a few key locations. A series of emotional and visceral jolts whose brute power and intensity could not be conveyed by a conventional linear story. A seamless block of passionate memories defined by the beauty and terror of the everyday.

The problem with all these descriptions of Distant Voices, Still Lives is that though each is partially accurate, they only dance around the periphery of what is a primal experience; that they represent the shards of my attempts to describe the essence of a masterpiece that reinvents filmgoing itself. I saw it twice at the Toronto film festival last September, and twice again earlier this month, and the inadequacy of my efforts is largely due to the fact that great films have a way of imposing their own laws and definitions that ordinary descriptions can’t reach. Read more

This appeared in the July 26, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Up Down Fragile

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Laurence Côte, Marianne Denicourt, Nathalie Richard, Pascal Bonitzer, Christine Laurent, and Rivette

With Côte, Denicourt, Richard, Anna Karina, André Marcon, Bruno Todeschini, Wilfre Benaiche, Enzo Enzo, and the voice of László Szabó

The inspiration of Up Down Fragile? The MGM low-budget films of the 50s that were shot in four or five weeks on sets left over from other films. In particular, a Stanley Donen movie, Give a Girl a Break [1953], a simple film shot in next to no time with short dance numbers. — Jacques Rivette in an interview

Entertainment does not…present models of utopian worlds, as in the classic utopias of Sir Thomas More, William Morris, et al. Rather the utopianism is contained in the feelings it embodies. It presents, head-on as it were, what utopia would feel like rather than how it would be organized. — Richard Dyer, “Entertainment and Utopia”

Out of Jacques Rivette’s 17 features to date — in which I include his 12-hour serial Out 1 (1970) as well as both parts of his Jeanne la pucelle (1994) — 9 are set in contemporary Paris. Read more

1. GREED (Stroheim, 1924)

2. SUNRISE (Murnau, 1927)

3. THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS (Welles, 1942)

4. CITY LIGHTS (Chaplin, 1931)

5. LOVE ME TONIGHT (Mamoulian, 1932)

6. THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES (Wyler, 1946)

7. STARS IN MY CROWN (Tourneur, 1950)

8. LOVE STREAMS (Cassavetes, 1984)

9. A.I. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (Kubrick & Spielberg, 2001)

10. WHEN IT RAINS (Burnett, 1995) Read more

This commissioned essay was for a touring retrospective catalogue, The American New Wave, 1958-1967, published by the Walker Art Center and Media Center/Buffalo in 1982 (and slightly tweaked just now, in June 2010). It’s dated by my erroneous assumption, shared by most critics during this period, that the dialogue of Shadows was improvised, corrected years later by the research of Ray Carney — although I still stand fully behind my opening paragraph. I was also mistaken in my assumption that Charles Mingus was entirely responsible for the film’s score, especially in the second version. (Ross Lipman has written brilliantly and in detail on this subject.)

My writing of this article was both interrupted and ultimately informed by the shock of the suicide of my older brother David. Regarding the details about lapsed Catholicism apropos of The Savage Eye, I can still recall a phone conversation I had at the time with the late Veronica Geng, a former colleague at Soho News (and lapsed Catholic) and a writer and editor at The New Yorker whom I plumbed for information and advice. Perhaps I went a little overboard in my expressions of scorn for the purple prose in The Savage Eye’s commentary; today I find it rather fascinating for its kinship with Beat writing from the same period, for better and for worse. — Read more

From the September 24, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

American Beauty

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Sam Mendes

Written by Alan Ball

With Kevin Spacey, Annette Bening, Thora Birch, Wes Bentley, Mena Suvari, Chris Cooper, Peter Gallagher, and Allison Janney.

American Beauty is a brilliant satirical diagnosis of what’s most screwed up about life in this country, especially when it comes to sexual frustration and kiddie porn. Or American Beauty is a hypocritical piece of kiddie porn, brilliantly exploiting an audience’s sexual frustration and turning it into coin. Take your pick.

Paradoxical as it sounds, both of these statements may be true. American Beauty is, after all, a Hollywood movie, like The Graduate (1967) and Risky Business (1983), two somewhat comparable historical markers that gleefully conflate social criticism and fantasy wish fulfillment so you can’t tell them apart. Whether American Beauty will become a hit like those earlier movies is hard to predict, but if it doesn’t it won’t be for lack of trying. Like The Graduate, it sympathizes with rebellion and satirizes complacency, but that doesn’t stop it from taking digs at sexually deprived middle-aged women as if they were somehow the root of all evil. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (November 21, 1997). I tend to respect Verhoeven more nowadays than I did back then. — J.R.

Starship Troopers

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Written by Ed Neumeier

With Casper Van Dien, Dina Meyer, Denise Richards, Jake Busey, Neil Patrick Harris, Clancy Brown, Seth Gilliam, and Patrick Muldoon.

When did American action blockbusters stop being American? Sometime in the last two decades, in between the genocidal adventures of George Lucas’s Star Wars and those of Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers, the national pedigree disappeared. True, Starship Troopers is a simplified, watered-down version of Robert A. Heinlein’s all-American novel, and it’s consciously modeled on Hollywood World War II features (as was much of Star Wars); it even boasts an “all-American” cast that could have sprung full-blown from a camp classic of Aryan physiognomy like Howard Hawks’s Red Line 7000. But the only state it can be said to truly reflect or honor is one of drifting statelessness. If the alien bugs that populate Verhoeven’s movie wanted to learn what American life and culture was like in 1977, Star Wars would have served as a useful and appropriate object of study; but if they wanted to know what American — or even global — life was like in 1997, Starship Troopers would tell them zip. Read more