From Sight and Sound (October 2008), in response to a poll query about what film criticism had had the greatest effect on me and inspired me to become a film critic — J.R.

From Penelope Houston’s review of Last Year in Marienbad in the Winter 1961-62 issue of Sight and Sound:

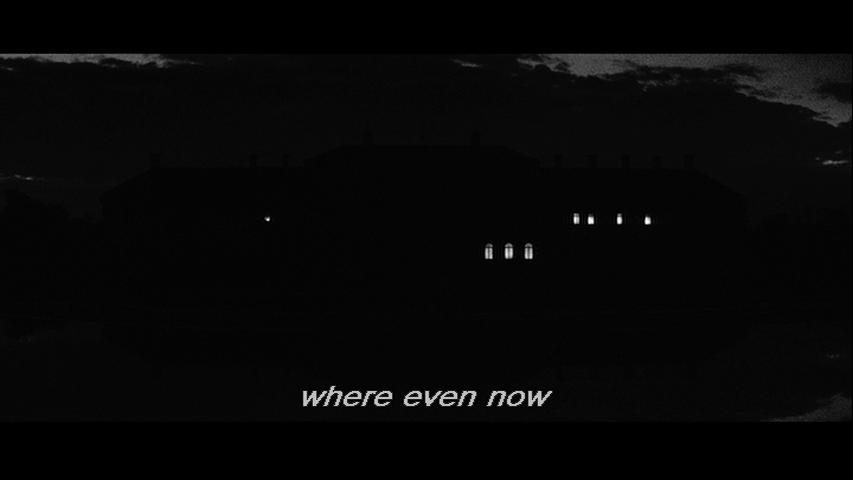

…And so she goes to the midnight meeting with the stranger, sits waiting rigidly for the clock to strike, leaves with him. But about this ending there is no sense of exaltation or relief. She goes because she has no choice, because for her all the possibilities have narrowed down to a single decision, but she has no idea where she is going. The stranger’s final words offer no comforting clue: “It seemed, at first sight, impossible to lose yourself in that garden… where you are now already beginning to lose yourself, for ever, in the quiet night, alone with me.” The film’s last shot is of the great chateau; and, with its few lighted windows, it no longer looks like a prison but like a place of refuge.

I read this review in my late teens, before I saw Resnais’ glorious masterpiece and quite a few years before I ever met Penelope. To this day, it’s the most sensitive and sensible review of the film that I know, in English or French, written in beautifully cadenced prose that provided me with an introduction to one of cinema’s least describable – and some would say most intractable – experiences.

Much later, in the late 1960s, I engaged with film criticism more directly by editing an anthology called Film Masters that for various banal reasons was never published, and Penelope’s definitive review was one of its first and happiest selections – eventually leading first to correspondence with Penelope and then to meeting her on one of my first visits to London, a good five years before I joined the staffs of Sight and Sound and Monthly Film Bulletin. To the best of my knowledge, the review has never been reprinted anywhere else – a shocking fact, but maybe not so shocking if one considers how much of the very best English film criticism (eg the collected works of Raymond Durgnat and Tom Milne) has been allowed to remain out of sight and out of reach.