From the Chicago Reader (November 21, 1997). I tend to respect Verhoeven more nowadays than I did back then. — J.R.

Starship Troopers

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Written by Ed Neumeier

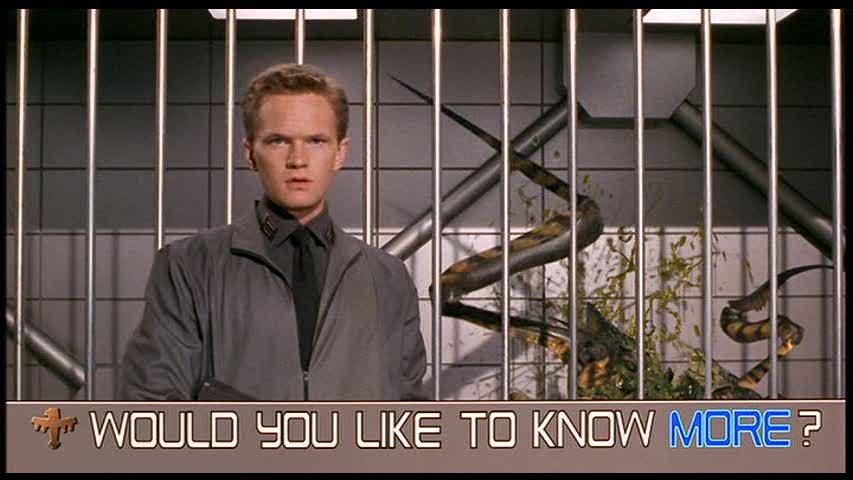

With Casper Van Dien, Dina Meyer, Denise Richards, Jake Busey, Neil Patrick Harris, Clancy Brown, Seth Gilliam, and Patrick Muldoon.

When did American action blockbusters stop being American? Sometime in the last two decades, in between the genocidal adventures of George Lucas’s Star Wars and those of Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers, the national pedigree disappeared. True, Starship Troopers is a simplified, watered-down version of Robert A. Heinlein’s all-American novel, and it’s consciously modeled on Hollywood World War II features (as was much of Star Wars); it even boasts an “all-American” cast that could have sprung full-blown from a camp classic of Aryan physiognomy like Howard Hawks’s Red Line 7000. But the only state it can be said to truly reflect or honor is one of drifting statelessness. If the alien bugs that populate Verhoeven’s movie wanted to learn what American life and culture was like in 1977, Star Wars would have served as a useful and appropriate object of study; but if they wanted to know what American — or even global — life was like in 1997, Starship Troopers would tell them zip.

Both movies might be loosely described as odes to American values set in a fanciful future mixed with the half-remembered midcentury past, but the similarity is only skin-deep — and not just because Verhoeven hails from the Netherlands. (Starship Troopers is probably even less Dutch than it is American.) Star Wars was made at a time when American pop cinema still belonged mainly to Americans; now it belongs mainly to global markets and overseas investors, and because so-called American cinema is the brand that sells best in international markets, that’s what it says on the label. But what’s inside the package is, properly speaking, multinational, not national — which in thematic terms involves subtracting ideas rather than adding them. Maybe that’s why loss of identity was the very theme of Face/Off — another recent multinational action special, and one whose success perhaps marked the end of John Woo’s career as a director of Hong Kong action films.

By national cinema, I mean a cinema that expresses something of the soul of the nation that it comes from: the lifestyle, the consciousness, the attitudes. I wouldn’t want to quibble with anyone who argues that Starship Troopers is American in the same way or to the same degree that french fries are French. What I mean is something more delicate and complex — a matter of substance more than packaging yielded by most national cinemas over the past century, but no longer available to us in most multinational blockbusters.

For a movie to belong to a particular national cinema often means that it has a stronger impact on its home turf, as the recent American art movie In the Company of Men did. In France the film was cursorily dismissed by the two leading critical film magazines, Positif and Cahiers du Cinéma, while at the Viennale in Austria last month, which I attended, its impact seemed minimal alongside other current American films, even Joe Dante’s made-for-cable The Second Civil War. I suspect this is because taboos against discussing capitalism critically, which gives In the Company of Men much of its subversive impact in the United States, don’t exist in the same fashion in Europe. But a pseudo-American farrago like Starship Troopers will likely be appreciated (and avoided) for the same reasons everywhere on the planet: high-tech special effects, severed limbs, and lots of action.

Superficial enjoyment isn’t really the issue. I like bug crunching as well as the next fellow — although this movie dishes out more of it than I could possibly want — and there are a few kicks to be had from Verhoeven’s sneering use of recruitment commercials, his handsome if unoriginal styling of interstellar navigation, and his (all too rare) glimpses of future cityscapes. The point is that calling this and other expensive action-explosion specials “American” only further confuses our already alienated and divided self-image. And to assume so cavalierly that this movie is exactly what teenage boys everywhere are itching to see overlooks the heaps of contempt for that demographic constituency that the movie dispenses every chance it gets. A lot of reviewers have been wondering whether the jeering satire directed at the teenage crowd will sail right past them, but if the audience I saw Starship Troopers with is any indication, the movie elicited only sporadic laughter and applause laced with hints of self-contempt, and overall the enthusiasm seemed to wane toward the end. It seems to me that we’re all too eager to share the movie’s disdain for its target audience (“A new kind of enemy, a new kind of war,” say some of the ads — as if alien insects and 50-year-old weaponry were innovations), just as we’re much too docile about accepting the film’s blood lust as American.

Consider what Verhoeven says in the press book: “When I came to the United States I felt that initially I wouldn’t know enough about American culture to make movies that accurately reflected American society. I felt that I would make a lot of mistakes because I would not be aware of things such as expressions and social behavior.

“I felt I could make science fiction movies because I wouldn’t have to worry about breaking any rules of American society. Science fiction reflects those rules but does not represent them.” From this point of view, Verhoeven’s 1987 RoboCop and 1990 Total Recall represent successive steps toward Starship Troopers; wacko fantasies like his Basic Instinct and Showgirls offer variations on the same rootlessness. All five films project different versions of the same hyperbolic comic-strip iconography, the same garish, overblown characters, and the same sarcastic and gloating contempt. In fact it was arguably Verhoeven’s awkward attempt in Showgirls to say something about America — Hollywood in particular — that spelled its commercial doom: this is a film that fundamentally said “We’re all whores, aren’t we?” The American public answered, in effect, “Speak for yourself.” Starship Troopers modifies that statement to read “We’re all stupid apes and cannon fodder, aren’t we?” And this time audiences all over the world, more accustomed to receiving such epithets as a natural part of their action kicks, are somewhat likelier to agree (though, depending mainly on gender and age group, some might disagree).

But whether this movie excites the desired euphoria among potential warmongers, American and otherwise — at least to anything like the same degree as Star Wars — is another matter. In the Lucas scheme of things wiping out entire planets is clean, bloodless fun that never threatens the camaraderie between fuzzy creatures and humans, who trade affectionate wisecracks while zapping enemies from afar; mythical conceits derived from Joseph Campbell only enhance and ennoble the fun. Verhoevian genocide, by contrast, has no such pretensions: it’s a messy affair involving extensive dismemberment on both sides, loads of blood and goo, loss of privacy and comfort, and only a modicum of emotional satisfaction — in short, none of the media pleasures offered by demolishing Baghdad. Most of us Americans probably know as little about Iraqis as the starship troopers do about the alien bugs they fight, and the topography of the bug planet, as Dave Kehr pointed out in the New York Daily News, “suggests the scene of the Gulf War.” But there the similarities end — especially after one factors in the anachronistic weaponry and forms of combat in Verhoeven’s movie, most of it derived from 40s and 50s war films, and the enemy’s power to retaliate.

The incidents that ignite the wars in Starship Troopers and Star Wars are hardly the same either, however rudimentary in both cases. When Luke Skywalker loses his relatives to alien villains, we’re invited to spend at least a few seconds commiserating with him to validate his desire for payback. But when the parents of Johnny Rico (Casper Van Dien) get nuked — among 12 million other earth dwellers, no less — what we’ve already seen of this pair makes them only slightly less repellent than the bugs who wipe them out, so the tragedy and outrage are strictly rhetorical. Just about the only glimpses of private life we see are of this yammering couple in their home: is this the life on earth worth risking one’s life and limbs for? By comparison the coed showers and 20 minutes allotted for sex between battles (two perks of committed army service) are considerably more attractive. (The lead characters’ home base is “Buenos Aires” — a dimly defined setting with no traces of Latin culture whose loss is about as wrenching in this movie as stubbing one’s toe.)

The militarized fascist utopia in Starship Troopers — presented mainly in the form of interactive recruiting commercials — is so sketchy that ironically its main virtue seems to be a leveling of class differences among the volunteer soldiers, the only citizens allowed to vote — though who or what any of them might vote for is anyone’s guess. In effect the movie is a collection of shots and characters designed to circle the globe rather than to say anything much about either the filmmakers or the audience, a triumph of multinational capital at work rather than of people or ideas.

Paradoxically, Heinlein’s tiresome but genuinely American 1959 novel reveals a good deal more of international life than Verhoeven’s ersatz American movie. But that’s because 38 years of American history –including the cold war and its aftermath and the passage from both nationalism and internationalism to multinationalism — separate these two versions of the Good Fight. In the novel, boot camp for the fighting youth of earth’s galactic empire includes the son of a Japanese colonel working on his black belt and two Germans with duelling scars; Johnnie Rico himself, also known as Juan, is the son of a Filipino tycoon and in one of the novel’s delayed revelations turns out to be black. Boot camp in the movie, by contrast, is basically American white-bread with a few multicultural trimmings — a reflection of neither the 50s nor the 90s but an incoherent mishmash of the two. Boot camp is also coed, which is presumably supposed to reflect the future. (The novel featured women pilots, but not unisex showers and sleeping quarters.)

As critic H. Bruce Franklin rightly points out in his 1980 book Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction, the writer’s “right-wing” militarism actually reflects the liberal ideology of John F. Kennedy, who was elected president a year after the novel was published. The armed force in Starship Troopers anticipates the creation of the elite Green Berets; Kennedy’s signature “Ask not what your country can do for you” speech also seems to come straight out of the novel. Written as Heinlein’s 13th in a juvenile series for Scribner’s (a series celebrating the conquest of space whose first filmic incarnation was the 1950 Destination Moon, adapted from Rocket Ship Galileo), the book was rejected for its extreme and unapologetic militarism, then published as an adult novel by Putnam. It’s another indication of how much we’ve changed in 38 years that adults in 1959 had the quaint notion of shielding teenage boys from this sort of thing — though the novel lacked most of the movie’s graphic gore (which is now aimed at them).

Franklin also points out that Starship Troopers — which is as steeped in cold war ideology as Heinlein’s 1951 The Puppet Masters, and thus in striking contrast to his neo-hippie and neo-communist Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) — suggests that the alien bugs represent Chinese communists and that another humanoid race (the “Skinnies,” omitted in the movie) reflects Russian communists. In fact the novel is crammed with pompous lectures about the communist menace and the errors of Karl Marx, most of them linked to the bugs’ “hive” mentality — which makes it all the more ironic that the classless military utopia Heinlein proffers as an ideal alternative is no less socialist and totalitarian. The movie actually intensifies this paradox by showing how impossible it is for Johnny to speak to his girlfriend or his parents on the videophone without all his bunk mates being present.

Visually, the movie bugs on their home planet recall the giant ants of the 1954 Them! (another cold war allegory) and the attacking natives of the 1964 Zulu. But ideologically they’re boring ciphers without any discernible language, culture, architecture, or technology — apart from their capacity to bomb earth and suck out people’s brains. They’re creatures of action storyboards rather than anyone’s notion of a society. And this being a Paul Verhoeven film, humanity doesn’t fare much better, either on-screen or off.