From the Chicago Reader (March 10, 1989). It’s sad to hear that the great and irreplaceable Jackie Burroughs passed away on September 22, 2010. — J.R.

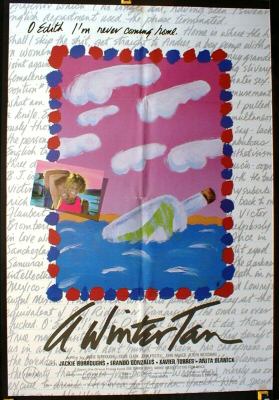

A WINTER TAN

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jackie Burroughs, Louise Clark, John Frizzell, John Walker, and Aerlyn Weissman

Written by Burroughs

With Burroughs, Erando Gonzales, Javier Torres, and Diana d’Aquila.

A Winter Tan is startling because it mainly succeeds in its aims though they’re based on at least three dubious premises. The first is that a volume of letters can be adapted into a plausible dramatic film. The second is that the letters in question — an American woman’s descriptions of her sexual adventures in Mexico, written before she was murdered, probably as a result of a sexual escapade — can be seen as exhilarating and life-enhancing instead of just depressing. And the third dubious premise is that a film made collectively by five directors can come across with a singular voice and style, a consistent meaning and purpose.

I haven’t read Maryse Holder’s book Give Sorrow Words, which was published posthumously some years ago, first by Grove Press in hardcover and then by Avon in paperback, and is currently out of print in both editions. The film came about at an anticensorship benefit in 1984 at which Canadian actress Jackie Burroughs performed excerpts from Holder’s letters from Mexico to her Canadian friend Edith Jones. This led to discussions between Burroughs, John Frizzell, and producer Louise Clark about making a film out of the material, a project that was facilitated by the additional participation of cinematographer John Walker and sound person Aerlyn Weissman.

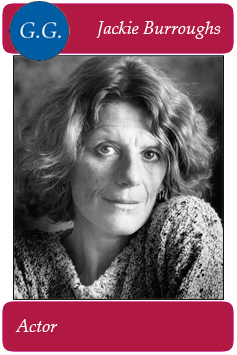

Ironically, this collectively conceived and generated feature comes across very much like a one-woman show, a “concerto” for Burroughs (who is probably best known in the U.S. as the female lead in The Grey Fox). Indeed, without Burroughs’s capacity to bring a certain charismatic range and inflection to the letters, the project probably would have been unthinkable. But at the same time, it is worth noting that Burroughs’s spiritual affinity with Holder is not matched by any congruence in appearance or age. According to filmmaker Mark Rappaport, who knew Holder in school — and is incidentally an enthusiastic fan of A Winter Tan — she was at least a decade or more younger than Burroughs is in the film, she was shorter and heavier, and one side of her mouth was paralyzed. The film has to be regarded as a work of fiction in which the letters of Holder play a central role rather than a biopic in any ordinary sense. Regarding the circumstances of Holder’s murder, the film remains almost completely reticent, although whether this is due to lack of information or to other motives is not clear.

The film opens with an actress playing Holder’s Canadian friend Edith seated in semidarkness explaining the context of the letters — how she encouraged Holder, who had artistic ambitions as a writer, to keep sending her letters from Mexico, with the idea that they might eventually be collected into a book. The camera passes over some of these letters and accompanying photographs (or, rather, facsimiles of them) as Burroughs recites a letter offscreen, then we cut to the event being described — the departure of Andreas, one of Holder’s young Mexican lovers, from her sparsely furnished room. The recitation then continues on-screen, as if she’s talking to herself as she gathers up her books, tears some photographs from the wall, hastily packs, and then walks with her baggage to another hotel.

Sometimes, in the course of the film, Holder addresses herself; sometimes she addresses the camera; and at still other times she addresses whomever she happens to be with — lover, friend, or acquaintance — all the while reciting the text of actual letters. Occasionally these varying forms of address slide briefly into a naturalistic context as dialogue, but we never lose sight of the fact that what we’re hearing is highly literary and reflective prose being written to someone thousands of miles away; and part of Burroughs’s triumph is her graceful way of handling all the permutations in this fragile conceit, allowing us to respond to her lines both as prose and as drama.

“I’m on a vacation from feminism,” she remarks at one point to a fellow sunbather, and a little later she muses to herself, “It’s too bad Latin feminists are all Marxists and lesbians.” Despite the questionable and unfashionable nature of such remarks, as well as the unbridled hedonism of Holder’s life in Mexico (which included generous amounts of booze, grass, and cocaine as well as sex), there’s little doubt that Holder was a feminist as well as a sensualist, and that by her own admission she was looking for love as well as sensation. Clearly a complex and self-aware individual, Holder can’t be neatly or strictly pigeonholed according to the usual cliches about promiscuity and female self-loathing that are usually associated with such behavior — the Looking for Mr. Goodbar mind-set that is invariably decked out with puritanical notions about decadence, masochism, and fatalism.

This is not to deny a certain pathos in the character’s efforts to escape or transcend her middle-class background. The point is that the combined intelligence and imagination of Holder and Burroughs make her quest into something richer and more variable than our usual responses to such situations would suggest. At one point she’s looking in a mirror while undressing and dispassionately evaluating her body parts; at another she’s attending a bullfight and arguing that women really don’t like machismo, contrary to what her current lover Lucio says.

One way of appreciating the nuances of her particular brand of slumming — which obviously isn’t for everyone — is to compare her attitudes and use of graphic language to those of such male counterparts as Henry Miller, Charles Bukowski, and other literary epicures of the lower depths. While Miller and Bukowski often seem to exult in the idea of obscenity, Holder uses words like “pussy” and “cock” strictly functionally, as referents, suggesting that she’s more interested in what these words mean than in whether they are shocking. Clutching a bottle of liquor and a copy of Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal on a train, she notes (to faraway Edith), “I’m a lush, my dear — prefigured by my own fears and by Lowry’s awful Mexican novel.” This passing put-down of Malcolm Lowry’s remarkable yet preening Under the Volcano — an accomplished high-art monument to self-pity, like its various avatars (including John Huston’s reductive 1984 film adaptation) — provides us with an even better clue to all the things she’s not. An existential heroine, she’s not helpless or “doomed” or self-posturing or lost; she knows what she’s doing, and mainly likes it — and Burroughs is the ideal vehicle for conveying her enjoyment. “I gave him the most perfect blow job of all time,” she says of Lucio, “after which,” she adds proudly, “he said I was a professional.” And much later, writing rapturously of her “four days of perfect love” with Miguel, the last and most important of her lovers, she describes with some awe his “pulling snot from her nose” with “no disgust, like a cat cleaning a kitten.”

The filmmaking style brought by the five directors to this subject is both fluid and varied: a monologue delivered by Holder as she sunbathes on a beach ends in a freeze-frame; the crosscutting during the train ride is achronological (and seemingly atemporal); and her arrest for public drunkenness and consorting with a 14-year-old boy is punctuated with the sound of a slamming door. (“Well, you can’t force a country to love you, right?” she notes to the camera sanguinely after emerging from jail, and continues cheerfully, “The warden was right — I lay with scum.”) Each of these film devices is arrived at honestly — as a logical outgrowth of the material and not as a superimposed external effect that draws us away from it. The film’s treatment of sex is comparably sophisticated: managing to be neither chaste nor prurient, it deals with eroticism with much of the same curious combination of matter-of-factness and lyricism found in Holder’s correspondence.

The movie’s limitations are the dramatic and narrative limitations of the intimate letters, which alternate between anecdote and reflection, without the shaped or “finished” coherence found in a polished piece of fiction. Indeed, the main continuity offered is one of character, and this is furnished at least as much by Burroughs’s flavorsome performance as it is by the letters that serve as her libretto.

Whether she’s “hitting the Acapulco pool-crashing scene,” brooding alone in a public square about being stood up (“Men know how our desire for love overwhelms our intelligence; they know it all over the world”), luxuriating in her lovemaking with Miguel, or plotting revenge for seemingly having been abandoned (“If he shows now, I’ll make a satisfying scene, believe me”), Burroughs brings to the part both a rare suppleness and a sense of firm conviction. In spite (or maybe because) of the extra distance from the character that she brings to the role, she creates a persona with uncommon variety and density. In her long virtuoso soliloquy at the end, pacing back and forth in a disheveled hotel room, she assumes so many divergent relationships to the camera and to ourselves that what finally emerges is a fully rounded portrait, whose mysteries and ambiguities are a vital part of its reality and presence.