From Film Comment, July-August 2000; slightly tweaked in April 2023.

MADADAYO

Akira Kurosawa, Japan, 1993

Given the unwarranted abuse that has greeted the final works of so many major filmmakers – an honor roll stretching from Anatahan to Eyes Wide Shut that also takes in the precious, misunderstood last features of Dreyer, Ford, Hitchcock, Ivens, Lang, Renoir, Preston Sturges, and Tati – one shouldn’t be too quick about dismissing Kurosawa’s curious swan song, released when he was 83, five years before his death. Based on several books by the popular sketch and essay writer Hyakken Uchula and parcelled out in a series of separate episodes, Madadayo focuses on the declining years of a retired German professor (Tatsuo Matsumura) and his interactions with his adoring former students (all male), his wife (Kyoko Kagawa), and two household cats. The title literally means “not yet” – a child’s teasing, sing-songy reply to the question “Are you ready?” is a game of hide-and-seek. And by essentially saying this for 134 minutes, not once but many times, and at a snail’s pace, all the way up through the concluding dream sequence, this limpid octogenarian’s film is bound to try some people’s patience. For those who locate Kurosawa’s achievement exclusively in the samurai action films he made with Toshiro Mifune in the Fifties and Sixties, it may be an outright insult.

One such commentator – Tony Rayns in a Sight and Sound obituary – didn’t even find such films as Ikiru, I Live in Fear, and High and Low worthy of mention. Stressing that “as a thinker, Kurosawa is of very little interest” – a statement that could also be made about Griffith and Chaplin – Rayns pointed out that “there is a direct line between the eco-humanist guff of the late films and the facile moralism of the early ones.” It’s certainly true that, having been overtouted since the Fifties, at least in relation to Ozu and Mizoguchi, Kurosawa now seems in danger of being dismissed altogether in some quarters, and Madadayo is not exactly the feature one would select for mounting an adequate counter-defense.

Speaking as someone moved by all the “eco-guff” and antiwar passion in I Live in Fear, Dreams, and Rhapsody in August, as well as by the free play of fantasy in the latter two films, I have to admit that there’s a kind of solipsism in Madadayo that mainly registers as Kurosawa’s homage to himself via his loosely-defined hero. Symptomatically, all the other characters, cats included, are effectively deprived of any identity apart from their relation to this benign, wisecracking patriarch. I suppose one could say the same about the West Point phys-ed instructor played by Tyrone Power in Ford’s The Long Gray Line (1955), a sentimental valediction with roughly the same running time. But that film had Maureen O’Hara and CinemaScope – not to mention some sustained glimpses of Marty Maher teaching other students before all this experience gets recollected in tranquility years later. By contrast, Madadayo begins with the camera fixed interminably on a closed door (the same way Dreyer’s Gertrud ends), until a student rushes through it to announce breathlessly, “He’s coming!” The Professor arrives, very formally, and after cracking a couple of jokes to the gathered students, announces that it’s his last day of teaching.

The sequence ends with an abrupt cut from the Professor blowing his nose to the title “Tokyo, 1943” – perhaps the movie’s most visceral moment. It’s the year when Kurosawa’s first film was released, so the Prof’s retirement seems to give birth to his own career. The remainder of the story, covering about two decades, is so bereft of incident – apart from the hero’s moves to two new residences and several casual visits – that it borders on nonnarrative reverie. Perversely, that’s what I like about it: that it virtually reverses the action-packed macho-Mifune strain in Kurosawa’s work to attend with endless fascination to a wobbly, reedy, sedentary type who bursts into tears when his cat vanishes.

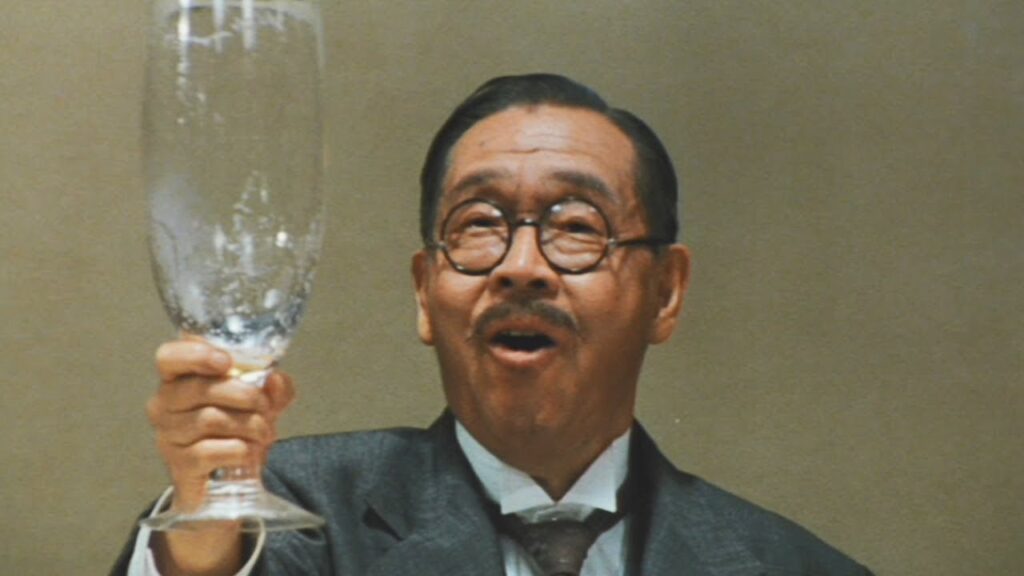

There’s lots of space devoted to showing how much the Professor’s former students revere him – we get two out of 17 commemorative banquets (neither with any of the irony of the one in Gertrud, the final one here lasting 20-odd minutes) – but very little attention given to showing why: his talents teaching German and as an all-around sage remain unexamined, taken for granted. This makes Madadayo limited, though I certainly wouldn’t call it barren – or bitter and spiteful like Hawks’ Rio Lobo, to cite another swan song I find problematic. As a reflection on running out of steam that suitably doesn’t even find much to say on the subject, Kurosawa’s inner-directed mumble at least can’t be accused of any pretension or platitude; it’s simply a way of trying to find some peace with himself. And its best defense may be its sense of freedom. “What greater homage could one pay to an artist of the cinema in the mid-20th century than to quote Rossellini’s remark after he saw A King in New York: ’It is the film of a free man’?” Godard on Rossellini on Chaplin in the early Sixties is clearly mapping out a program that also encompasses Rossellini’s practice in the Fifties – not to mention Godard’s own freedom in the Sixties in dealing with anything and everything in his features, with Rossellini and late Chaplin as two of his ethical guides.

To be free in these terms means to prattle, and Kurosawa prattles fearlessly and shamelessly, ultimately beyond caring whether we approve or not. This doesn’t put Madadayo in the same league as The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie – or Manoel De Oliveira’s 1998 Inquietude, for that matter – except insofar as, even though he’s bereft of irony, Kurosawa seems every bit as free as Buñuel and Oliveira, who have little else. He’s certainly unafraid to let his emotions hang out and to leave them hanging raw: the sequence detailing the loss of the Professor’s ginger cat Nora is so glutted with grief that it makes something like E.T. seem repressed by comparison.

Jonathan Rosenbaum