From The Real Paper (January 17, 1973).

As I recall, this was my only contribution to this Boston alternative weekly, commissioned by the late Stuart Byron. He asked me to review the film because I was the only colleague of his who defended it when it was shown at the 1972 New York Film Festival, where everyone else, at least within his earshot and mine, considered it an unmitigated disaster — which probably accounts in part for my defensive, almost apologetic tone, which I now regret. I suspect that part of my problem with conceptualizing the film came from my confusion of “science fiction” with the French category of “fantastique,” which incorporates Surrealism and its tolerance for fantasy as well as science fiction. So it’s gratifying to see Manohla Dargis declaring the film a masterpiece at the time of its early 2014 run at New York’s Film Forum, and doing an infinitely better job of saying why than I was able to muster 40-odd years earlier, writing from Paris….Fans of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind are urged to check out this film, in many ways its major inspiration. — J.R.

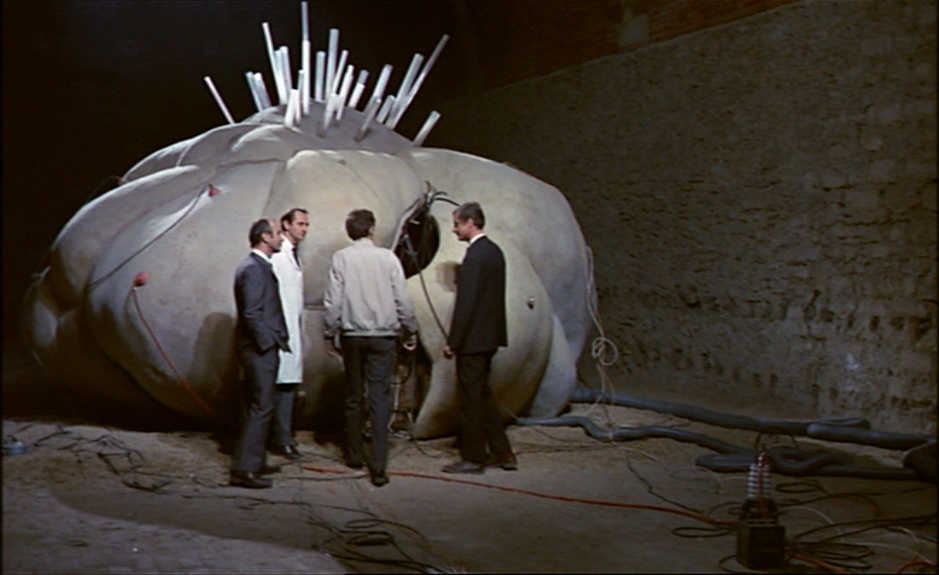

At first glance, Alain Resnais’ fifth feature seems as sharp a decline from La Guerre est finie, his previous film, as that one was from Muriel. The science-fiction situation that frames the main body of the narrative is so clumsily sketched in and illogically developed that it emerges as unintelligible; we can accept the time-travel experiment that goes haywire and sends its subject bouncing through the previous year of his life either as an awkward contrivance leading us into the past of Claude Ridder (Claude Rich) or not at all. The narrative also stumbles over the problem of convincing us that the achronological fragments of Ridder’s past are random while simultaneously arranging them in the kind of rigorous structure we always find in a Resnais film.

At first glance, Alain Resnais’ fifth feature seems as sharp a decline from La Guerre est finie, his previous film, as that one was from Muriel. The science-fiction situation that frames the main body of the narrative is so clumsily sketched in and illogically developed that it emerges as unintelligible; we can accept the time-travel experiment that goes haywire and sends its subject bouncing through the previous year of his life either as an awkward contrivance leading us into the past of Claude Ridder (Claude Rich) or not at all. The narrative also stumbles over the problem of convincing us that the achronological fragments of Ridder’s past are random while simultaneously arranging them in the kind of rigorous structure we always find in a Resnais film.

If one can rationalize these embarrassments, or accept them as cumbersome but necessary pretexts, there is a great deal to be moved by in Je t’aime, je t’aime. As in Last Year at Marienbad and Muriel, the studied banality of the dialogue and images is a precise instrument for conveying a sense of the unknowable. (The score, which resembles a Swingles Singers number put through electronic variations, echoes the film’s other efforts to formalize banality.) The true subject of the film is not what we know about the hero’s life, but what we can never hope to learn. Most of the incidents in the film which are repeated most often — Ridder emerging from the ocean in flippers, or waiting on a street corner somewhere for a bus — seem to carry in themselves the least expressive meanings, but their obsessive repetitions impress us, as in the tortured prose of Faulkner, with the romantic agony of pounding on a door that will not open.

Jacques Sternberg’s script weaves around the periphery of Ridder’s unhappy love affair, defining and conveying it through its contours alone, and Resnais’ direction respects the mysteries of cause and condition that underlie this anguish. Like the mouse that accompanies Ridder for part of his time-journey, and is shown in the last shot trapped under a glass bell, Ridder is locked into a past that is inexpressible and and irredeemable, and the beauty of the film resides in its capacities to convince us of this. The emotional conviction of this intensity is felt behind and between the images more than within them, but we cannot deny its palpable presence.

— Jonathan Rosenbaum