From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 2000). — J.R.

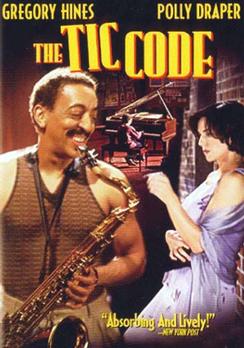

The Tic Code

**

Directed by Gary Winick

Written by Polly Draper

With Gregory Hines, Draper, Christopher George Marquette, Desmond Robertson, Carol Kane, Carlos McKinney, Dick Berk, John B. Williams, and Tony Shalhoub.

Writing about Finnegans Wake, James Joyce’s most musical book, the late William Troy had the perspicacity to point out that “a word, in the terminology of modern physics, is a time-space event. It is not too much to say that for the poet no word in a language is ever used twice exactly in the same way.” Since a musical note is also a time-space event — repeatable on paper, CD, or tape but not in live performance — existentially speaking an improvised jazz solo is a journey, a dramatic and social act that can happen only once.

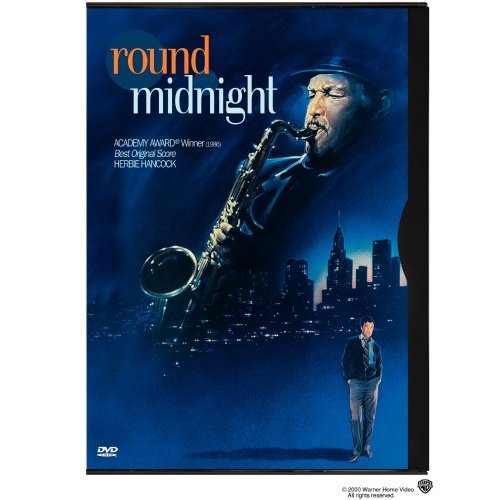

It’s possible to capture certain aspects of jazz performances in words, as critic Whitney Balliett and novelist Rafi Zabor (in the wonderful The Bear Comes Home) have amply demonstrated. But what film can do poetically with jazz solos is much less certain. It might be argued that most films and most jazz solos have stories to tell, but getting their stories to coincide is not an easy task. Usually the music in film is demeaned, often receding in a matter of seconds from the story’s foreground to its background — typically buried under dialogue and reduced to “atmosphere.” Even the few features made by genuine jazz buffs have often bristled with competing agendas. When Dexter Gordon’s over-the-hill expatriate musician plays a relatively tired solo in Bertrand Tavernier’s Round Midnight, the music tells two stories — and its importance as a piece of characterization supersedes its interest as a piece of music. When Forest Whitaker mimes Charlie Parker playing a much better solo in Clint Eastwood’s Bird, the characterization and music merge, but it might be said that the film’s story about Parker is suspended so that the story of Parker’s solo can briefly take center stage. (Much more successful and brilliantly integrated is the jazz performed by four actor/characters in the film version of The Connection [1961], where the music effectively takes over the narrative of Jack Gelber’s play, turning all the other on-screen events into background.)

So it’s a matter of considerable importance and excitement to me that The Tic Code includes a few ecstatic moments when the movement of the plot and the unfolding of a musical performance miraculously fuse, creating a mysterious, indissoluble unit. The most striking instance is a duet performed at New York’s Village Vanguard by a precocious 12-year-old pianist named Miles Garrity (Christopher George Marquette) and an adult tenor saxophonist named Tyrone Pike (Gregory Hines). The effort isn’t sustained beyond a few moments from several performances spread out over a handful of scenes, and eventually the reflex of atmospheric “background” jazz takes over. But for a few brief stretches, at least, this movie offers glimpses of the promised land.

I’ve rated this film two stars — “worth seeing” — but it’s an unambiguous must-see for jazz fans. Despite occasional dramatic shortcomings — the unconvincing, abrupt ending is especially unfortunate — its handling of the jazz milieu and the music itself is unique. (Though the filmmakers skimped on some details — the Village Vanguard is used in exterior shots, but the Down Time is used for interiors — overall the West Village ambience seems right.) And the beautifully detailed and inflected central performances — especially those by Marquette, Hines, Polly Draper as Miles’s mother, and Desmond Robertson as Todd, Miles’s best friend — are sweet and warm.

Race and illness are as important as jazz in this movie, but only in relation to the characters, not as separate issues. Miles and his mother are white while Tyrone and Todd are black. And both Miles and Tyrone suffer from Tourette’s syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary grunts, jerks, spasms, grimaces, noises, curses, imitations, and other compulsive physical actions — seizures that the film sometimes conveys through sudden transitions from color to black and white. Frankly, I came to this movie skeptical that its subject could mean much more than strident Oscar mongering, given the precedent of such films as Rain Man. But The Tic Code goes out of its way to deal with Tourette’s honestly and unsentimentally, and it’s as serious about this disability as it is about jazz.

Draper (best known as Ellyn in Thirtysomething) is the film’s screenwriter as well as its formidable lead actress, drawing on the experiences of her husband, Michael Wolff, a jazz pianist who has a mild case of Tourette’s syndrome. (He composed the film’s music and has a cameo as a recording engineer.) Apparently it’s not uncommon for “Touretters” to be “remarkably musical,” according to Oliver Sacks in his essay on Tourette’s syndrome in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. “Witty Ticcy Ray,” his eponymous subject, was “a weekend jazz drummer of real virtuosity, famous for his sudden and wild extemporisations, which would arise from a tic or a compulsive hitting of a drum and would instantly be made the nucleus of a wild and wonderful improvisation, so that the ‘sudden intruder’ would be turned to brilliant advantage.”

A major concern in both Sacks’s essay and this movie is an ambiguous zone of behavior in which Touretters are able to appropriate their involuntary physical movements and integrate them into willed expressions of various kinds. Jazz improvisation is one gray area among several in which accidents and creative accommodations to them rub shoulders. Miles’s vocal imitations, for example, are sometimes seen as symptoms of his condition, sometimes as evidence of his brilliance at coping with that condition, and sometimes as both. Each imitation must be evaluated separately — as we see being done by his resourceful mother, Laura, a single parent who works as a tailor and lives with Miles in the West Village.

This variability creates a lot of difficulty for other people in Miles’s life who have to interpret his behavior from moment to moment. Misunderstandings are frequent, ranging from acquaintances interpreting his movements as hiccups or laughter to his insensitive divorced father (James McCaffery) considering Miles’s condition to be a form of neurosis he needs to outgrow. Even Miles’s music teacher (Carol Kane) at the special school he attends ties his method of fingering piano keys to his condition. And the film opens and periodically returns to a video of Thelonious Monk (seen in Charlotte Zwerin’s 1988 documentary Thelonious Monk: Straight No Chaser) performing and dancing between solos at a concert in a way that suggests he might have had an undiagnosed case of Tourette’s.

Speaking broadly, the film’s only real villain is Miles’s father, also a jazz pianist. He’s moved to the west coast, so we — and Miles — see him only once, in an airport lounge: evidently he left his wife and son because he couldn’t cope with his son’s condition. Somewhat more redeemable is the chubby school bully who picks on Miles until Tyrone holds him at bay with an imaginative, obfuscating gloss on Tourette’s syndrome that gives the movie its awkward title: “Why do you suppose Miles and I both do this?…Because we both know the code….The CIA knows all about this.”

Clearly Miles needs a more appropriate father and Laura needs a husband — which leads them to Tyrone. But we soon discover that, despite his gifts as a father, lover, and musician and for all his resourcefulness in inventing the tic code, Tyrone copes with Tourette’s syndrome more often through denial than through acceptance and accommodation. So when he discovers that Laura has been following his club dates because of his condition in the hopes that he might help her with Miles, he feels more threatened than flattered, ultimately creating a rift between them.

The fact that Miles is free from the effects of the syndrome only when he’s asleep or playing the piano places him in a different category from Sacks’s weekend drummer. Witty Ticcy Ray wound up taking medication on weekdays to subdue his symptoms, then cut it out on weekends in order to revel in them when he played (Sacks often views the various neurological afflictions described in his book as mixed blessings). By contrast Miles prefers to avoid medication entirely because it dulls his creativity and makes his symptoms even worse once the effects of the arm patch wear off, and Laura supports him. So when he decides to wear the patch before going to see his father at the airport, it’s virtually an admission of defeat.

Sacks argues that a “medicinal, or medical” approach should be supplemented by an “existential” approach to such disorders as Tourette’s and Parkinson’s disease. He says that we must have “a sensitive understanding of action, art and play as being in essence healthy and free, and thus antagonistic to crude drives and impulsions, to the ‘blind force of the subcortex’ from which these patients suffer. The motionless Parkinsonian can sing and dance, and when he does so is completely free from his Parkinsonism; and when the galvanised Touretter sings, plays or acts, he in turn is completely liberated from his Tourette’s. Here the ‘I’ vanquishes and reigns over the ‘It’.”

It’s one thing for Miles to avoid the effects of Tourette’s by playing the piano — literalizing the notion of art as a utopian state of being for mind and body, thereby affording us glimpses of the promised land. But the issues of accident and accommodation hovering over his playing also have a larger resonance. Indeed, when he and Tyrone play their getting-acquainted duet at the Vanguard, the way they search for and discover each other in time and space is governed partly by chance and partly by a process in which life choices and artistic choices become indistinguishable.

Some may find Miles’s piano playing (dubbed by Woolf; Tyrone’s tenor playing is dubbed by Alex Foster) implausibly sophisticated for a 12-year-old. Yet the film’s overall treatment of this multifaceted, contradictory, bratty, brilliant, and above all erratic character is probably its finest achievement. Even if one winds up regarding this story as a fairy tale, the dialogue, performances, and music all take it to a higher level, making it seem closer to real experience than other movies based on more commonplace premises are able to do. I value the flawed Tic Code over a good many relatively flawless features because it has more heart, more life, and more spunk. It reminds me of what another Miles once said about treasuring mistakes in jazz performances: if you leave them out, you’re cheating.