From the February 18, 1994 Chicago Reader. I wrote this before I had a chance to see the film’s original rough cut, when it was still a musical, which I continue to regard as far and away James L. Brooks’ best movie, more than twice as good as what he finally released.. By contrast, the release version reminds me of Erich von Stroheim’s comment about the release version of his Foolish Wives: “They are showing only the skeleton if my dead child.” [2021 afterthought: This now strikes me as more than a little hyperbolic. Some of the musical version of the film is great, but a fair amount of it is weak and/or doesn’t work very well. For more on the subject, go here.] — J.R.

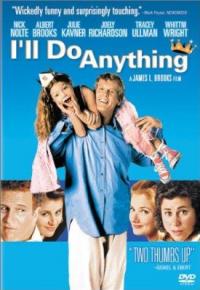

** I’LL DO ANYTHING

(Worth seeing)

Directed and written by James L. Brooks

With Nick Nolte, Whittni Wright, Julie Kavner, Albert Brooks, Joely Richardson, Tracey Ullman, Jeb Brown, and Angela Alvarado.

First riddle: How can a movie about Hollywood professionals also be a movie about learning to be a parent? Answer: When all the Hollywood professionals in the movie act like kids or parents.

However disjointed it felt the first time I saw it, James L. Brooks’s I’ll Do Anything took on a certain conceptual clarity the second time around. What was disconcerting at first — the leapfrogging between characters and, apparently, subjects — became coherent and meaningful once I understood that all the scenes are running variations on the same theme.

On the surface, the story proceeds more or less like this: Idealistic, dedicated, and mainly unemployed New York character actor Matt (Nick Nolte) proposes to his malcontent girlfriend Beth (Tracey Ullman) in Los Angeles in 1980. Seven years later, when their daughter Jeannie is six months old, we can see that Beth is miserable. About six years after that, following their divorce, Matt gets a call from Beth, now living with Jeannie in Georgia, informing him that he has to take his daughter for three weeks. After testing unsuccessfully for a part at Popcorn Pictures, where he renews his acquaintance with a young studio executive named Cathy (Joely Richardson), Matt winds up getting hired as a driver by the head producer, Burke (Albert Brooks). At a test-marketing preview he sees Cathy again and also befriends Nan (Julie Kavner), an audience-opinion researcher and single parent who’s becoming involved with Burke.

Matt discovers when he arrives in Georgia that he has to take Jeannie semipermanently because Beth is going to prison. Back in Hollywood, he struggles to control his bratty, unruly child, leaving her with a Hispanic neighbor while he drives Burke to previews. Cathy finally persuades Burke to let her develop her favorite project, a remake of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, and test Matt for the lead. When Matt goes over to Cathy’s house to read the script, she seduces him, but their lovemaking is interrupted by a string of phone messages on her answering machine, including one from Jeannie. While Matt’s taking his screen test Jeannie, waiting for him on the lot, gets cast in a multiracial TV show; meanwhile we catch glimpses of Nan’s unhappy affair with Burke . . .

This isn’t the whole plot — though I’ll be getting to more of that eventually, so let readers beware — but it’s enough to give you some notion of the overall form. As I’ve described it so far, the movie concentrates on four duos — Matt and Beth, Matt and Jeannie, Matt and Cathy, Burke and Nan — whose relationships are more personal than professional, and a few secondary and less dynamic duos, like Matt and Burke, Matt and Nan, and Cathy and Burke, whose relationships are more professional than personal. If we can’t figure out what making movies and being a father have to do with each other — a mystery likely to distract us on a first viewing — the fact that everyone generally behaves like a kid or a parent in every scene, whether the relationship is personal or professional, ultimately explains it. That Brooks has a daughter the same age as Jeannie undoubtedly motivates the connection he draws between moviemaking and parenting, and shows how personal his filmmaking tends to be; but justifying the connection is another matter.

We first see only mothers — Beth is clearly a bad one, Nan is clearly a good one, and Cathy is potentially a good mother, both to Jeannie and to Matt. (Also clearly a good mother is the neighbor, but she’s a less developed character.) All the men — Matt, Burke, and a snotty unnamed development executive (a “D person,” in industry lingo) — are clearly infants, and in the movie’s precise moral coding Matt is good, the D person is terminally bratty, and Burke is bratty but lovable. Jeannie, of course, falls into the bratty-but-potentially-good category. The remainder of the movie describes how Matt, Burke, and Cathy gradually assume their parental roles and Jeannie goes from being bratty to good.

I know this sounds awfully simpleminded, but we have to remember that Brooks owes his artistic formation to TV. (Among the many shows he’s been associated with are The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Tracey Ullman Show, Lou Grant, Rhoda, Taxi, and The Simpsons.) And to give him some credit, what would be simpleminded in a movie about parents and children is a little bit more interesting and subtle in a movie about Hollywood professionals — even if Brooks’s underlining of dramatic points still sometimes smacks of TV. When Matt tries unsuccessfully to discipline Jeannie on a plane trip, there’s an elaborate and wholly unnecessary camera movement leading to a close-up of him saying to a flight attendant, “I have no idea what to do.” On the other hand, Brooks’s sense of character is masterful. After leaving Jeannie with the neighbor, Matt hears crying and runs back, but is delighted to find that the crying comes from the neighbor’s little boy and not Jeannie. Brooks’s deft counterpointing of Matt’s childish delight with the neighbor’s maternal consternation about his response, all in a matter of seconds, is a pleasure — and offers an early clue that first impressions count for a lot in this movie. (Equally clever, one should add, are the characters’ apartments, which should probably be credited in part to coproducer Polly Platt’s feeling for dressing a set

Brooks also compares the professional and the personal in his last feature, the 1987 Broadcast News, set in Washington, D.C. — although there the characters behave more like siblings than like parents and children. In I’ll Do Anything the parallels between Washington and Hollywood are drawn by Nan, who moved to Hollywood from Washington: she has a speech early on about what the two company towns have in common, such as “overprivileged people” crazed by the fear of “losing their privileges,” alcoholism, betrayal, and “spiritual bloodletting.”

Second riddle: How can one be moralistic about morally ambiguous businesses, like mainstream journalism and entertainment, while remaining a part of those businesses? Answer: By focusing on the morality of personal decisions on the middle-management level and ignoring decisions made on the corporate level.

Both Broadcast News and I’ll Do Anything revolve around a moment when a performer is called upon to produce tears. In the earlier film, these tears are fake ones produced by a newscaster (William Hurt) while giving a report about date rape, and the producer (Holly Hunter) who’s about to run off with him on a tryst changes her mind when she learns from a friend (Albert Brooks again), the newscaster’s romantic rival, about the tears being faked. Broadcast News isn’t concerned with whether the news report was accurate or insightful in other ways; it simply joins the producer in her utter scorn for this corrupt behavior.

In I’ll Do Anything Jeannie knows she’ll be called upon to cry in the TV show she’s working on and is afraid she won’t be able to. Matt tells her there are only two ways to do it — to think of something that really makes her sad or to forget that she’s pretending — and at the climactic moment Jeannie opts for the former. In this case, producing tears on demand is seen as an unambiguous good, whether or not the TV show is defensible (a nonissue in the movie) and despite the fact that on more than one occasion Jeannie has manipulated her father by crying.

All this may seem to make Brooks an exemplar of the double standard, but it’s hard to simply dismiss him with the moral confidence he so often shows toward his own characters. When all is said and done, he still has an artist’s quirks and reflexes and can’t be written off as a hack. In all three of his features — the first was Terms of Endearment — he seems to put a TV frame around everything, then puts a movie frame around that: more than any other American director he embodies the contradictions of being an ambitious mass-media artist, precisely because of his reliance on such dialectical moves. Deliberately or not, he winds up deconstructing many of his own most questionable decisions: as J. Hoberman notes in the Village Voice (in a mainly unfavorable review), “So much is made of [Jeannie’s inability to cry on demand] that it’s an unavoidably Brechtian moment when she does,” and much the same could be said of many similarly self-reflexive elements in this picture.

In her comparison of Washington and Los Angeles Nan might have added that the media in both towns are run as meat markets — a point made in both Broadcast News and I’ll Do Anything, though both movies fail to follow through on the implications. As morality plays, the pictures are similar, with Matt assigned some of the characteristics of Holly Hunter and Albert Brooks in Broadcast News and Cathy assigned the villainous William Hurt part. Infuriatingly, in both films director Brooks blindly and abjectly accepts the worst everyday crimes of both TV news and Hollywood yet is self-righteously indignant at minor personal infractions. Thus he can be completely blasé about news shows’ most significant lies — crass ideological emphases and distortions — but furious when a newscaster fakes tears, which in the grander scheme of things can’t have many or even any important social consequences. Similarly, Brooks is cool about some of the worst sentimentalities and corruptions of movies (a 90s remake of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, or an executive trying to cast her lover in a big part) but burbles with rage about a momentary failure to follow through on a personal commitment — that is, the failure to openly support a lover as a commercial sex object during an executive meeting. Commercial sex objectification, on the other hand, is never questioned.

Brooks never considers the possibility that Matt might be wrong for the lead quite apart from whether women in the audience want to sleep with him or not. More on his mind is the meat market — a preoccupation that also informs Hurt’s ascendancy as a newscaster over Albert Brooks in Broadcast News. In I’ll Do Anything this preoccupation takes on unstated ethnic implications in the comic scenes between Burke and Nan, hinging on the way Jewish styles of behavior (suggesting a west-coast version of Woody Allen) exclude them from mainstream notions of glamour and beauty.

In the scene that comes closest to defying meat-market mentality, Matt flies into a very touching rage when he overhears the D person deliver an abusive litany of epithets while criticizing a colleague’s list of possible cast members for a movie: among others, “Ed Harris — losing his hair,” “Jeff Daniels — beanpole,” “Tommy Lee Jones — very unfortunate skin,” “James Spader — vanilla, vanilla, vanilla,” and “Raul Julia — bug eyes.” The gist of Matt’s response (“God, man, where did they find you?”), delivered in a stammering Method-acting manner meant to convey authenticity, entails a similar kind of total rejection, but the fact that Matt rejects the executive’s style rather than his physical appearance makes the rejection much more palatable from a humanistic standpoint. By contrast the D person’s griping comes close to the master-race brand of criticism, practiced most famously by film and theater critic John Simon. (And this kind of criticism doesn’t exist only in the mainstream: I’ll never forget a Village Voice review of a few years back that unabashedly dismissed the lead actress in an independent feature because her nose was “too big.”)

Despite Brooks’s apparent hatred for this mentality, his Manichaean tendency to divvy up his characters into saints and sinners, with no options for redemption or a fall from grace (perhaps a legacy of his TV background), leads to judgments nearly as monolithic. Characteristically oversimplifying, he establishes that Nan’s medications — antidepressants, plus pills for the side effects, plus pills to counteract those pills –add up to some kind of truth serum, which makes her incapable of telling a lie; and given the movie’s TV notion of the “truth,” we’re implicitly asked to assume that she can’t have “inaccurate” opinions. When at a climactic juncture she feels called upon to deliver a clinching moral verdict about Cathy to Cathy — that Matt is simply too good for her — we’re obviously meant to applaud and agree. At this point Cathy considerately vanishes from the scene — and the movie — for good, and Jeannie, skillful tear faker, effectively takes over as leading lady. (The fact that Jeannie, played by hammy five-year-old Whittni Wright, wears earrings even before her TV debut is the kind of material the movie never addresses. Are the earrings her idea, Beth’s, or Matt’s? None of these answers seems plausible.)

Third riddle: When is a movie not the work of a moviemaker? Answer: After it gets test marketed.

It’s been widely reported — even in the film’s official publicity, which may be a first — that I’ll Do Anything started out as a musical with a much longer running time, but that unsympathetic previews led Brooks to delete all the songs except for about half of one of them. Presumably we’re supposed to forget all that when we sit down to watch the picture, but I doubt many of us can. I’ve tried to honor this principle up to this point, ignoring this facet of the movie and treating the work on its own terms. Yet it’s impossible to deny that I’ll Do Anything felt incomplete as a comedy both times I saw it — not surprisingly, because in terms of how it was written and originally filmed it is incomplete, and all the recutting and reshooting in the world won’t make it otherwise. For all the film’s intermittent brilliance, the quality of the performances ranges from stridently awful (Ullman) to standard-issue sitcom (Kavner) to resourceful and lively (Nolte and Richardson) to cartoon gargoyle posing (Albert Brooks), and Wright runs the gamut of these extremes in nearly every scene. Whether the movie made more sense, eccentric or otherwise, before it got test marketed into its present state of choppiness is anyone’s guess, but it’s hard to imagine it didn’t.

I doubt that there are many things in Hollywood more ruinous to movies than the principle of mob rule that lies behind test marketing. It’s inconceivable that a movie like Citizen Kane could have survived previews, and the same could be said of any movie that steps off the beaten path and can’t be absorbed without a moment’s reflection. Though previewing movies makes sense in determining how to publicize them, previewing them to determine how to make them seems more a form of hysteria than a form of business or art — yet most industry reporters treat test marketing as if it were a hallowed, proven science rather than a high-tech form of fortune-telling. (Remember, these are the soothsayers who reported that The War of the Roses would flop.) This practice epitomizes the short-term, kamikaze Reaganite approach to economics, which has driven this country into terminal debt. Declaring a movie a hit or a bust even before its opening weekend is fully compatible with making decisions on the basis of hastily arrived at, “definitive” projections and spinelessly junking long-term strategies.

If any proof were needed that previewing is largely a joke, a story in the December 17, 1993, Wall Street Journal, “Film Flam? Movie-Research Kingpin Is Accused by Former Employees of Selling Manipulated Data,” offers plenty of confirmation. Though Joseph Farrell of National Research Group Inc., the firm handling most Hollywood test marketing — including the kind we see in I’ll Do Anything — denies the accusations, the story reports that about two dozen former employees “ranging from hourly workers to senior officials,” mostly people who left the firm voluntarily, claim that the research data is sometimes doctored to conform to what clients want. (All the examples in the story involve boosting a movie’s score, as with Teen Wolf, L.A. Story, and The Godfather, Part III. But one can well imagine the deck being stacked the other way when studios perversely want certain good films to fail — most recently and blatantly, Paramount and The Thing Called Love and Warner Brothers and The Body Snatchers.)

It’s characteristic of Brooks that he believes so religiously in test marketing that he tore the guts out of his own movie to prove his faith. But what has he proved? If he wants to show his conviction, perhaps he should credit his preview audiences, not to mention advance reviewers, as codirectors and coeditors. But personally I feel cheated and more than a little insulted: why should the reflexes of preview audiences be carved in stone, thereby determining my own long-term experience of the movie?

As it stands, I’ll Do Anything is full of scenes that promise emotional release and don’t deliver it. Stories in the press make it plain that most of these — a scene between Burke and Nan in a restaurant, and another of Matt and Cathy conversing over car phones — originally featured songs. Obviously the preview audiences didn’t respond well to these, or to nonsingers like Kavner and Nolte singing — just as many people I know, including some critics, don’t like Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons singing in Guys and Dolls (1955), though I happen to find it both sexy and moving. It’s possible that I wouldn’t like the songs in I’ll Do Anything, but I’d much rather dislike them than dislike their absence — not to mention dislike the audiences whose passing fancies determined my permanent lack of choice in the matter.