From the August 28, 1992 Chicago Reader; reprinted in my collection Placing Movies. — J.R.

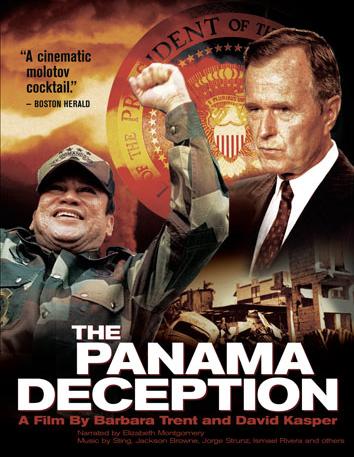

THE PANAMA DECEPTION

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Barbara Trent

Written by David Kasper

Narrated by Elizabeth Montgomery.

DEEP COVER

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bill Duke

Written by Henry Bean and Michael Tolkin

With Larry Fishburne, Jeff Goldblum, Victoria Dillard, Charles Martin Smith, Sydney Lassick, Clarence Williams III, Gregory Sierra, and Roger Guenveur Smith.

I wonder how many people under 35 know that one of the most frequent taunts hurled at President Lyndon Baines Johnson during antiwar demonstrations at the height of the Vietnam war was, “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” Johnson did considerably more than any other U.S. president of this century to turn the civil rights movement into law — even going so far as to appropriate the movement’s theme song, “We Shall Overcome,” for a speech to Congress. But because of his behavior regarding nonwhites overseas, especially in Southeast Asia, a considerable part of the youth of the late 60s regarded him as a mass murderer, and told him so on every possible occasion. It seems plausible that Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection in 1968, announced only four days before Martin Luther King was assassinated, had more than a little to do with the repeated sting of that relentless chant.

If any of the young people of today consider George Bush — who has done precious little for civil rights — a mass murderer because of Panama and the Persian Gulf, I have yet to hear about it. Some of this may be the fault of the media, which, as part of their totalitarian coverage of military interventions in those countries, have tended to minimize and undercut most public opposition to them, and some of it probably has to do with the fact that our economy — which was unusually strong during the 60s — now makes many of us less prone to care about the fates of innocent nonwhites in foreign countries. (Whether it makes us totally indifferent, as some claim, is another matter. If we were, the tightly controlled state censorship in the cases of Panama and the Persian Gulf — which wasn’t in effect during the war in Vietnam — surely wouldn’t be necessary.)

As luck would have it, I happened to see most of Barbara Trent’s highly informative The Panama Deception immediately before George Bush’s upbeat speech at the Republican National Convention last week. As a result, I had the surreal experience of going directly from the somber parade of horrors caused by the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989 — 20,000 Panamanians homeless, more than 18,000 forced into detention centers, 7,000 arrested without charges, thousands of civilian deaths, mass graves evoking Nazi exterminations, an estimated doubling of local cocaine traffic since Noriega’s capture, a brutal U.S. military occupation now projected into the indefinite future — to Bush in Houston euphorically boasting “I feel great!” and “The cold war is over and freedom finished first.”

Like Trent’s Coverup: Behind the Iran Contra Affair (1988), The Panama Deception is clearly timed to influence the presidential election, and it will be interesting to see if the carefully documented Bush bashing will reach a more receptive audience this time around. (Either way, perhaps we can look forward to a documentary from Trent about the Persian Gulf in time for the 1996 election — though I hasten to add that Bill Clinton appears to support the mass murder of innocents in that venture almost as fully as Bush does. As one commentator in the film points out, Panama was in many ways a “testing ground for the Persian Gulf war one year later,” and the progression from Iran-contra to Panama seems equally logical.) Back in October 1988 — 14 months before the Christmas-season invasion of Panama was launched — Coverup started an extended run at Chicago Filmmakers, which is now granting the same treatment to The Panama Deception. PBS, on the other hand, reportedly agreed to show Coverup only if every reference to Bush in the film were deleted — a highly comical suggestion almost tantamount to removing every reference to Panama from the new film. (PBS also recently refused to show Deadly Deception, the documentary short criticizing General Electric that won this year’s Academy Award. Naturally the GE-owned NBC and CNBC won’t be showing it either, but I’m told that Evanston and Lincolnwood cable subscribers can see it on Monday, August 31, at 6 PM on public access channel 29. Ain’t freedom grand?)

Both of Trent’s documentaries — the first scripted by Eve Goldberg, the second scripted and edited by David Kasper — are careful and lucid after-the-fact clarifications of government lies. So, in a way, is Deep Cover, a powerful and beautifully directed Hollywood thriller about Bush’s so-called war on drugs that opened on April 15 and has been running almost continuously in Chicago ever since. The three movies give compatible, even complementary views of Bush’s support of the drug industry — dating back at least as far as his using Noriega as his principal Panamanian contact when he became director of the CIA in 1976, upping Noriega’s annual salary to over $100,000, and agreeing to stop monitoring his drug dealing. In fact, one could go directly from The Panama Deception to Deep Cover, as I recently did, and discover a coherent account of how our freedom-loving government has directly collaborated in the proliferation of crack babies and related fruits of free enterprise.

As far as I can tell, hardly any of Deep Cover’s reviews, press coverage, or advertising (assuming that one can distinguish between the three) has even so much as hinted that the movie is a frontal assault on the hypocrisy of Bush’s war on drugs. It’s an essential part of that much-celebrated freedom of ours — the freedom that “finished first,” and that now theoretically allows the former communist bloc to compete with the U.S. in the crack market, starvation, and firearms — that we rigorously enforce what we already believe to be true so that we don’t run the risk of proving ourselves even slightly wrong. Critics constantly maintain that no one ever goes to movies for political reasons or responds to movies politically, and they write their reviews accordingly. So when a movie like Deep Cover comes along and clearly strikes a chord in audiences, critics don’t notice. It’s also part of our received wisdom that no one cares at all whether or not Bush is a mass murderer — that people vote for candidates exclusively on the basis of their own pocketbooks. This means that Deep Cover must be drawing people in for reasons other than its story or its theme, and that Bush’s failing popularity has nothing to do with his foreign policy.

The problem is, given the limits of our allegedly free mass media when it comes to certain matters — the Washington Post, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, and the Wall Street Journal all uncritically supported the absurd government pretexts for invading Panama, and as Trent’s movie shows, the United Nations’ condemnation of the invasion got ten seconds from Dan Rather on CBS and no mention at all on NBC — how can we evaluate what’s going on in the world in the first place? We’re landlocked about a good many matters, and often as not we don’t even know it. Postmortems like The Panama Deception are certainly helpful in pointing out how we were misled, but because most media events depend on our short attention spans — so that, for instance, Woody Allen was a flawless visionary genius in the spring, has become a pathetic degenerate numbskull this summer, and surely will embody some equally hyperbolic fabrication in the fall — they don’t necessarily prepare us for seeing through future media bamboozlements.

Although The Panama Deception does a fair job of showing how the invasion of Panama was systematically misrepresented in the U.S. press, it leaves out one prime instance of obfuscation, based on a mistranslation from Spanish to English, that surely would have enhanced its overall analysis. An official statement in Spanish saying in effect “It’s as if we were at war with the United States” was translated without the subjunctive in early media reports and became an alleged (albeit farfetched) declaration of war on the part of Panama, thereby serving to justify the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians more effectively than the bogus claim of “protecting American lives” ever could.

The Panama Deception also makes us acutely aware of the wider problem of evaluating any information we get in the news. Defending the basic integrity of the U.S. press, a friend recently argued that the only possible reason no one except Lynda Edwards in the March 1992 Spy ever reported on the two additional sworn testimonies from women about sexual harassment by Clarence Thomas — testimonies that never came up either during the Hill-Thomas hearings or in the press immediately afterward, though they were presumably available at the time — is that the story didn’t check out; if it had, my friend said, the New York Times, the Washington Post, et al, would surely have run it. Why, then, I wondered, couldn’t they have run a story showing that the Spy story didn’t check out? On a recent trip to Europe I discovered that the London Guardian had run essentially the same story as Spy, and for all I know countless other foreign papers ran it as well. But unless we have access to these overseas reports (and most people don’t), we have to depend on what our own press chooses (or chooses not) to shove our way.

Part of what keeps The Panama Deception so watchable is the various styles of lying it offers. Bush, a Pentagon spokesman, an Army general, and a Panamanian government flunky each have a different manner of contradicting the evidence of our eyes and ears (including blocks of ravaged neighborhoods and the eloquent and angry testimonies of many Panamanian civilian victims), though it shouldn’t be assumed that none of the military officials we see is candid or forthcoming. (It’s Rear Admiral Eugene Carroll who freely admits about the invasion, “The fact that it could cause tremendous peripheral damage, damage to innocent civilians on a wide scale, was not of concern in the planning.”) A capsule history of relations between the U.S. and Panama since the 1800s helps to show that the grim logic behind our present military occupation is nothing new, and a commentator toward the end explains how “the invasion sets the stage for the wars of the 21st century.” All that seems relatively new about Panama and the Persian Gulf, really, is the degree to which the public’s initial understanding of such events can be orchestrated, and Trent’s movie is invaluable precisely for showing us the strings of the puppeteers.

Deep Cover is a fable about a black undercover drug agent who calls himself John Hull (Larry Fishburne). The son of a junkie who was killed holding up a liquor store one Christmas, Hull joins the police force determined to put an end to the drug trade, not realizing that it’s the police and the government who contrive to keep the drug trade flowing and the kingpins protected. The kingpin in this case proves to be a Latin American politician named Guzman who could easily be mistaken for Bush’s pal Noriega before he got uppity; we learn that Guzman “goes fishing with George fucking Bush” and “is a friend of our president” (for the record, Noriega is mentioned directly in the dialogue as well). Hull is appalled to discover that he has to disobey his white boss (Charles Martin Smith) and get fired in order to go after this creep.

I’ve been told that when Michael Tolkin (The Rapture, The Player) wrote or cowrote the original version of the script, the hero was white, but the studio that financed the deal got either him or someone else — perhaps cowriter and coproducer Henry Bean — to make the character black, then dropped the project altogether when New Jack City came out and became associated with ghetto violence. The new script got picked up by New Line Cinema. The movie is a telling case of how sometimes the best results can grow out of the most incoherent or arbitrary deliberations.

I’m not sure when Bill Duke — the talented black actor who previously directed A Rage in Harlem and the TV film The Killing Floor — got assigned to direct this, but there’s no question that his remarkable feeling for editing and acting rhythms does as much for this movie as the punchy vernacular dialogue and the moral force of the plot. A good example of Duke’s editing rhythm is his use of staccato jump cuts, including what appear to be forward zooms broken up by skip framing, or eliminating every other frame — a rhythm that suggests a needle skipping across a record and that perfectly captures the panicky Los Angeles drug milieu the hero penetrates. In direct contrast to this druggy, hyperactive editing is Fishburne’s manner of registering dramatic points by calmly raising or lowering his eyes, motions that come across as cool fluctuations in the center of a hurricane.

Other riffs in the movie include the hero’s narration, which approximates at times a kind of rap poetry; the structure of the plot, which pointedly uses blood-soaked paper money as a motif and has the hero oscillating between his boss and his drug partners; and the implications of the hero’s impersonation of a drug dealer, which recalls a memorable line from Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night: “We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” (His undercover identity has a kind of dialectical irony worthy of Bush himself, and one that the script milks at every opportunity. “Undercover, all your faults will become virtues,” the hero’s boss tells him at the onset of his adventures; much later, the hero mordantly remarks offscreen that while he used to be a cop pretending to be a drug dealer, now he’s a drug dealer pretending to be a cop.)

I can’t claim that Deep Cover is a masterpiece. There’s an uncertainly conceived subplot involving an implausibly synthesized “designer drug,” and the religious beliefs of another black cop, evoking some of Tolkin’s preoccupations in The Rapture, are shoehorned awkwardly into the proceedings. The denouement is neatly brought off, but it mixes so many fanciful Hollywood wish fulfillments that it ultimately mars — or at least needlessly complicates — the singular bitterness and lucidity of the closing scene.

On the other hand, Duke’s corrosive direction of the violence and the sheer stench given off by Jeff Goldblum’s uncharacteristically slimy performance as a jumpy Jewish lawyer-gangster are as striking as anything I’ve seen in an American movie this year. And the moral and political force of Deep Cover‘s statement is so clear that I suspect only a film critic could fail to recognize it; to all appearances, sizable portions of the public have already found their way to this movie’s truth without benefit of media “experts” — mainly, it would seem, through word of mouth. In other words, a significant part of the public has already voted against Bush’s euphoria; whether they’ll carry this insight all the way to the polls is of course another matter.