From the August 4, 1995 issue of the Chicago Reader. My thanks to Chris Petit for reminding me (on Memorial Day, 2010) that I wrote this. I’ve heard, incidentally, that Godard prefers the original title of JLG/JLG to its American release title, the one given here. — J.R.

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Eddie Constantine, Hanns Zischler, Claudia Michelsen, Andre Labarthe, and Nathalie Kadem.

JLG by JLG

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

With Godard, Andre Labarthe, and Bernard Eisenschitz.

Like most of Jean-Luc Godard’s recent work, Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991) and JLG by JLG (subtitled December Self-Portrait, 1994) are annexes to his Histoire(s) du cinéma, a work on video in multiple parts scheduled to premiere in its finished form at the Locarno film festival in Switzerland in early August. (Four portions of this video have already shown at the Film Center.) Like the various parts of Histoire(s) du cinéma, these films (each about an hour long and being shown together at Facets Multimedia) are above all collections of carefully arranged quotations — interwoven anthologies of extracts from prose, poetry, philosophy, films, musical works, paintings. They differ from Godard’s magnum opus in that they’re films rather than videos and in their juxtaposition of quotations and exquisitely framed landscapes, German in Germany and Swiss in JLG. But like the videos they’re more hermetic personal essays about the modern world than narratives in any ordinary sense. These rich tapestries of rumination essentially invite us to listen to Godard talking to himself, and they resemble each other in that they’re probably the two most Germanic and melancholy films he’s produced since the 60s.

Born in Paris to Swiss parents, Godard has maintained an ambiguous Franco-Swiss identity throughout his life (he’s currently 64): in the 70s he moved back to the Geneva area, where he’d spent much of his childhood, though he still maintains an office in Paris. It’s not entirely clear what sort of role German culture plays in his background, but he’s often alluded in interviews to the fact that the German occupation of France occurred during his adolescence.

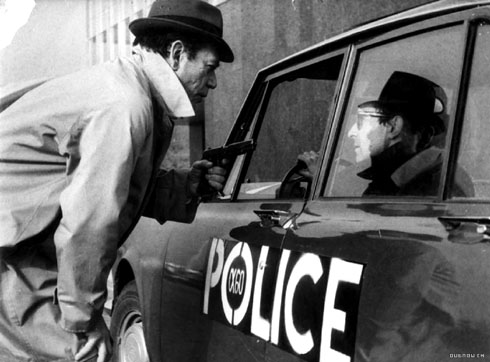

Germany Year 90 Nine Zero in particular harks back to Godard’s Alphaville (1965) — the most Germanic by far of his 60s movies — by focusing on that movie’s lead character, Lemmy Caution, played by the same actor, Eddie Constantine. Paradoxically Constantine is American by origin and French by association: born in Los Angeles, he was a protégé of Edith Piaf and became a nightclub singer in Paris. In 1953 he began appearing in French action thrillers as Lemmy Caution, the hard-living American private-eye hero of Peter Cheyney mysteries. By the time Godard appropriated Constantine and his character for Alphaville — a SF pastiche shot in contemporary Paris but set in a distant galaxy — Caution was something of a camp cliché, but Godard used his weary machismo to suggest tragedy as well as parody. Shot in very-high-contrast black and white, Alphaville took shape as a complex meditation on the German expressionist cinema of the 20s: it’s densely packed with references to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films and Metropolis, and F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, The Last Laugh, and Faust, as well as subsequent expressionist works like Cocteau’s Orpheus, Orson Welles’s The Trial, and various American comic strips. In Alphaville Caution is a spy from the “outer lands” of contemporary culture, posing as a reporter for “Figaro-Pravda” (the “Times-Pravda” in the English-dubbed version), moving through the nightmarishly depersonalized, computerized labyrinth of Paris/Alphaville like a skeptical primitive, embodying nostalgic reactions and stances from popular culture. (A discarded subtitle for the movie was “Tarzan vs. IBM.”)

A quarter of a century later Godard brings back Constantine’s Caution, again as a spy, but now he’s a forgotten mole in East Germany when the Berlin wall comes down — an anachronism who truly has no place to go. To some extent he’s even more of a stand-in for Godard than he was in the 60s, but it’s a different Godard he’s standing in for. No longer pretending in the same fashion to be a storyteller, and no longer tied so exclusively to cities, this Godard simply sets Caution loose in the German countryside and suburbs to gradually make his way to Berlin, plaintively asking everyone he encounters “Where is the West?” and receiving only blank stares. For Godard, the end of the cold war and the economic unification of Europe are occasions for mourning, not celebration — one of the first images we see in the film is a fallen Karl-Marx-Strasse street sign crushed under car wheels. And Caution is no longer campy or parodic; he’s simply a piece of tragic wreckage, a witness rather than a mover and shaker. (Constantine died shortly after this film was shot, in his mid-70s, and Godard records his final performance with moving gravity.)

Aside from certain touchstones, like Sigmund Freud’s “Dora” (one of his most famous cases) and Mozart’s Requiem, the quotations and references in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero are largely cinematic. The film’s title alludes to Roberto Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero (1947), set and shot in postwar Berlin, and the clips in Godard’s film include some color footage from Eric von Stroheim’s 1928 The Wedding March, shot in southern California but set in Vienna.

The references to German expressionist films also remind us of Alphaville, of course. As Lemmy Caution passes a bridge, the narrator says, “Once I was across the frontier, the shadows came to greet me” — a direct allusion to a famous intertitle in Murnau’s Nosferatu (“When he reached the other side of the bridge, the phantoms came to greet him”) that was praised by the father of surrealism, André Breton. At the end of Germany, Caution finally arrives at a Berlin hotel in a sequence that pointedly echoes the opening of Alphaville, when Caution arrives at a Paris hotel. The narrator says, “And yet the last man still went about his task,” a reference to Murnau’s The Last Laugh, which is titled “The Last Man” in German and French. In Alphaville a camera movement through the hotel’s revolving door alludes to the Murnau film, but here Godard includes a clip of Emil Jannings as the doorman in The Last Laugh helping people out of a cab, making the reference even more explicit.

When Caution arrives at the hotel in Alphaville, he’s taken to his room by a prostitute/maid, who checks to make sure that his room has a “Bible”: a dictionary containing all the words currently permissible in Alphaville. (New editions with fresh deletions are periodically issued to hotels; among the missing, forbidden words in Caution’s edition are “why,” “conscience,” and “love.”) The maid in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero is no longer a prostitute, but as she’s getting the room ready for Caution, she cites the Nazi slogan “Work makes you free,” reminding us that Caution had previously seen Nazi mementos being sold on the street alongside pieces of the Berlin wall. In both cases, emblems of the Nazi past have been politically neutralized by a certain historical amnesia. When Caution picks up the Bible in his Berlin hotel room and scans the pages, it almost seems he’s looking at one of the Alphaville dictionaries to see what words we no longer possess. “O, les salauds!” he says with weary disgust — “the bastards!” — and the film promptly concludes.

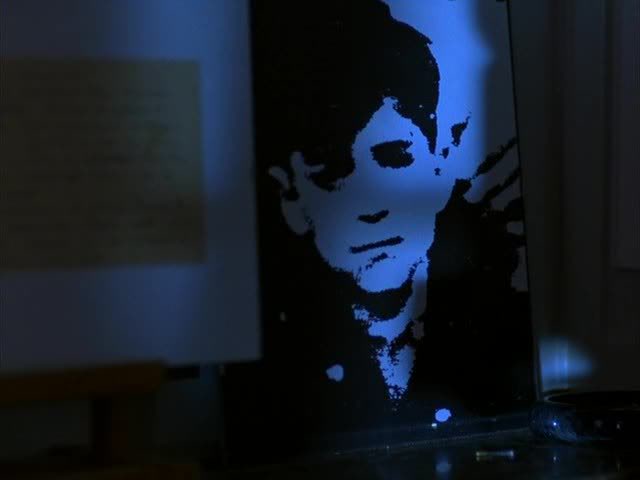

The Germanic aspects of JLG by JLG: December Self-Portrait are usually less obvious, having to do with the mood of German romanticism rather than the physical or cultural landscape of contemporary Germany. The weight of history, however, is just as heavy as in Germany Year 90 Nine Zero; but here it’s Godard’s personal history, signaled at the outset by a photograph of him as a boy that’s scrutinized by the camera at some length. Later the film refers to Godard’s own work, including even a patch of the sound track with Constantine’s voice from Germany Year 90 Nine Zero.

The quotations and art references are as plentiful as ever, but at times even more obscure. At one point Godard uses the phrase “The past isn’t dead — it isn’t even past,” but most reviewers seem unaware that the sentence comes from Faulkner. (This is a continuing problem of communication in a film that’s both translingual and transcultural, a problem that’s only exacerbated by Godard’s Mixmaster style.) And when in JLG we’re treated to the riffled pages of empty notebooks labeled “Roberto,” “Jacques,” “Boris,” and “Nicholas” accompanied by patches of movie dialogue in Italian, French, Russian, and American English, not all the references are easy to catch, especially for those living outside the French-speaking world: the famous exchanges between Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden in Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar are easily recognizable, and it’s simple to conclude that “Roberto” is Rossellini and “Boris” is Barnet, even if the dialogue can’t be identified. But when it comes to recognizing that “Jacques” is Rozier — the director of unexported French New Wave youth pictures like Blue Jeans and Adieu Philippine — and not Rivette, Demy, or Tati, most people will draw a blank.

A home movie in the most literal sense, and one that Godard explicitly calls “self-portrait — not autobiography,” JLG by JLG has the drawback of suggesting Goethe contemplating his own bust. (A powerful figure like Constantine breaks a movie out of Godard’s mind and into the larger world.) The ideas are every bit as rich and provocative as one would expect in a Godard film, and the sounds and images are every bit as beautiful (lonely snowscapes and choppy waves on Lake Geneva predominate), but the sadness and self-absorption have a cumulative oppressive effect. Even when the movie makes jokes, and good ones at that — “Europe has memories, America has T-shirts” — they aren’t very lighthearted. And when Godard cites the title I Am Legend, taken from a pulp novel by Richard Matheson, to comment on his sense of his own celebrity, the gesture seems arch and strained, neither clearly ironic nor clearly self-congratulatory.

Yet Godard’s intellectual channel surfing has been an important part of his manner and meaning since the beginning of his career. It’s an approach that has always entailed risks of this kind, but the rewards make them well worth taking. The fact remains that for all his abstraction and isolation in these films, Godard is able to see things going on in the world at present that most of his contemporaries make their living obfuscating. For 35 years, ever since Breathless, Godard has been defined by his hatred of mercantilism, not his lack of awareness of that world — yet industry flacks today suggest that Godard is somehow on cloud nine, in contrast to such “visionary” realists as Mike Ovitz, Ted Turner, and Rupert Murdoch. Those who dismiss Godard are simply afraid of how much he can see from that exalted vantage point. Like it or not, Germany Year 90 Nine Zero and JLG by JLG are essentially newsreels about the world we’re living in; it’s the media mavens, the lawyers, the bankers, and the agents who are the blinkered storytellers.