My column in the Winter 2021 issue of CinemaScope. — J.R.

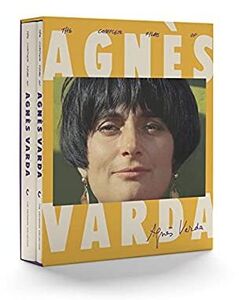

Teaching an online course on Agnès Varda at the School of the Art Institute this fall for 39 students has put me in regular touch with Criterion’s superb 15-Blu-ray box set, The Complete Films of Agnès Varda, every week. The packaging reminds me in some ways of the handsome 78 rpm albums I used to cherish as objects and totems in the mid- to late 1940s, when I was still a toddler, although Criterion’s version of this sort of assembly, held in a box, manages to be neater and more compact. There’s also a richly illustrated and annotated 200-page book inside the box, with essays by Amy Taubin, Ginette Vincendeau, So Mayer, Alexandra Hidalgo, and Rebecca Bengal, and excellent “program notes” on all the films by Michael Koresky. In short, plenty to keep a coronavirus shut-in busy, even without a course to teach.

The course has gradually brought home to me the complexly ambiguous lesson that Varda wasn’t really or exactly an auteur, at least not in the boys’-club meaning of that term as it’s most commonly used. But not being an auteur gave her a kind of freedom and a form of elasticity denied to most auteurs. I’m reminded of a problem I once heard Terry Gilliam expound upon at the Festival of the Midnight Sun in Lapland. To paraphrase his complaint, as I remember it: “All day long I’m surrounded by people who spend their lives trying to think up ‘typical Terry Gilliam touches,’ while I personally would much rather be doing something else, something atypical”—which is precisely what Varda most often wound up doing, frequently to both her profit and ours.

But much as typecasting is often the bane yet sometimes the triumph of much Hollywood acting, it also can sometimes shape auteurist thinking, beneficially or harmfully, by seemingly imprisoning both directors and the ways we accustom ourselves to thinking about them or expecting them to behave. The fact that Varda wasn’t really a cinephile, unlike her equally cross-referencing husband Jacques Demy, may have played a part in her not behaving like an auteur and approaching each project like a resourceful dilettante, starting from scratch. Learning, from a 2003 conversation with Polish composer Joanna Bruzdowicz (one of the Criterion set’s many extras), how Varda came up with the music and dolly shots in her masterpiece, Vagabond (1985), shows an independence and freedom of thought that arguably comes, at least in part, from not worrying about an oeuvre.

The weird creative osmosis occurring in and around Varda’s (or Demy and Varda’s) two-hour Jacquot de Nantes (1991) is an excellent case in point (and a convenient one, because the film was discussed in my course the same week that I’m writing about it here). While Demy was dying of AIDS (which was only acknowledged posthumously, many years later, by Varda), Varda apparently got him to write down some of his childhood memories (which we see him doing, or at least pretend to be doing, in the film), which she then set about staging and filming with actors, sometimes intercutting snatches of the Demy films inspired by these memories, preceded and followed by drawings of a pointed finger that serve as quotation marks for the clips. But for most viewers, including me and my students, it becomes to distinguish between what “belongs” to Demy and what “belongs” to Varda—not only auteuristically, but in terms of his or her memory and imagination, which ultimately become shared, collaborative pieces of property.

After writing the above paragraph, I belatedly watched the main extra for Jacques de Nantes, the 17-minute “Agnès Tells a Sad and Happy Story,” which was put together by Varda herself in 2008. (She helpfully and pithily introduces all the films included in the box set.) In fact, contrary to my account above, the video reveals that it was Demy who decided to write his own childhood memoirs, which apparently have never been published (it seems that his only published book as author is Chansons et textes chantés, which collects the librettos of musical films). When Varda, his first reader, remarked that they could make a good movie, he proposed right away that she should make it, insisting that he lacked the strength and energy to make it himself. But Demy was present during most of the shooting (carried out in Nantes, often at the events’ original locations), and much as Varda was the first reader of his written memoirs, he was the first audience of her filmed version as it was being shot. (He died only ten days after the end of shooting, so he never saw the edited film.)

So, is Jacquot de Nantes Varda’s film of Demy’s (creative) memory, or her film of her own (creative) version of his memory, with bits of his own films, selected by her, added to the mix? And what about those moments when some viewers can’t even tell which is which, when the whole conceit of auteurism discreetly evaporates? Or whenever Varda oscillates between black and white and colour in her restagings of Demy’s memories (which I argue in my class is a Brechtian device designed to prevent either version from registering as definitive), when we might ask ourselves which version is closer to his truth, or her truth, or our truth? Is she making this film for him, or is he writing this memoir for her? Even when present-day Demy takes over the narration, the ambiguity remains. And earlier, when Varda match-cuts between young Demy building a puppet theatre and his mechanic father working on a car, is the idea of these rhyming matches his or hers? Or is it theirs?

The only comparable instance I know of a shared authorship between a married couple, in which a live widow recounts a dead husband’s happy childhood, can’t be found commercially on any DVD or Blu-ray anywhere in the known universe; but it’s readily available with English subtitles on YouTube (where you can burn your own copy if you like) and it remains one of my all-time pantheon picks, and I can solemnly swear that this isn’t because it’s overlooked and neglected. I’m speaking, of course, of Jean-Luc Godard’s #1 favourite film of 1965, The Enchanted Desna, scripted by Alexander Dovzhenko but directed (in 70mm and stereophonic sound) after his death by his widow, Yuliya Solntseva (who had previously played the title role in the first Russian SF movie Yakov Protazanov’s 1924 Aelita, Queen of Mars)—a collaboration complicated further by the fact that Dovzhenko’s name is the only one to appear onscreen before the credits, as well as the recent revelation that Solntseva was a member of the KGB, which I suspect is what facilitated her lavish technical resources.

As I wrote of Dovzhenko in a piece for MUBI last spring, “a Cold War casualty, often defined in the West as a Russian increasingly difficult Communist and in Russia as a turncoat, this Ukrainian nationalist lived under KGB surveillance for most of his life—which may help to explain why his devoted second wife Yuliya Solntseva, who filmed many of his unrealized scripts after his death, had joined the KGB herself, possibly in order to protect her husband. And as one of his better Western explicators, Ray Uzwyshyn, has pointed out, ‘With regard to the non-Russian republics (i.e., Georgia, Armenia, Moldavia, Azerbaijan, et al.), the larger cinematic histories of these republics, like Ukrainian cinema, largely remains a blank slate for the West…”’ Even if I can’t begin to go along with Luc Moullet’s suggestion in Bref (a French magazine devoted exclusively to short films, which gave Moullet an excuse to review a segment of Solntseva’s 1971 Golden Gates, apparently the last of her Dovzhenko tributes) that Solntseva may have been a better director than her late husband, it’s worth noting that she was the first woman ever to win a directing award at a major European film festival, when her Chronicle of Flaming Years (also based on a Dovzhenko screenplay) took that prize at Cannes in 1961.

***

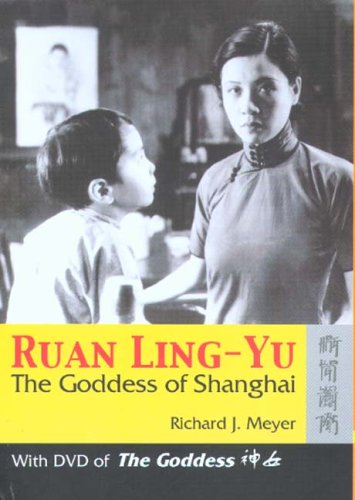

Although I purchased my own copy many years ago, I’ve been a slowpoke in acknowledging in this column a nifty book-and-DVD package, still in print, devoted to silent film actress Ruan Ling-yu, whose 1935 funeral (after she committed suicide at age 24) is said to have lasted three days and was attended by over 300,000 mourners. Richard J. Meyer’s Ruan Ling-Yu: The Goddess of Shanghai (2005), a 140-page paperback, comes with a DVD of the film widely regarded as her best, Wu Yonggang’s The Goddess (1934), complete with English subtitles, piano score, and audio commentary. This makes it an excellent complement to my favourite Hong Kong feature, Stanley Kwan’s Centre Stage(1991), a luminous biopic of Ruan starring Maggie Cheung, which is currently available on Blu-ray. It’s worth adding that four of Ruan’s films are available now with English subtitles on YouTube: the aforementioned The Goddess, Bu Wancang’s The Peach Girl (1931), Sun Yu’s Little Toys (1933), and Cai Chusheng’s New Women (1935). As to whether Ruan is the auteur of these films, or if Cheung and Kwan share the honours on Centre Stage, these are clearly matters that warrant further discussion.

***

The hell with critical justifications, auteurist or otherwise: our taste or our distaste for kitsch is largely determined by the age at which we first encounter it. I was eleven or so when I saw The Adventures of Hajji Baba (available on Blu-ray from Twilight Time and on DVD from a Spanish PAL import) at the Shoals Theater in Florence, Alabama circa 1954, having at the time a serious crush on Elaine Stewart and an enduring fondness for Nat “King” Cole’s campy and mantralike title tune, echo chamber and all. So reading about the undeniable talent of its director, Don Weis, in Présence du Cinéma almost two decades later arguably served more to justify my warmly remembered childhood bliss and celebrate my 11-year-old libido than to defend or rationalize any particular aesthetic position almost two decades later.

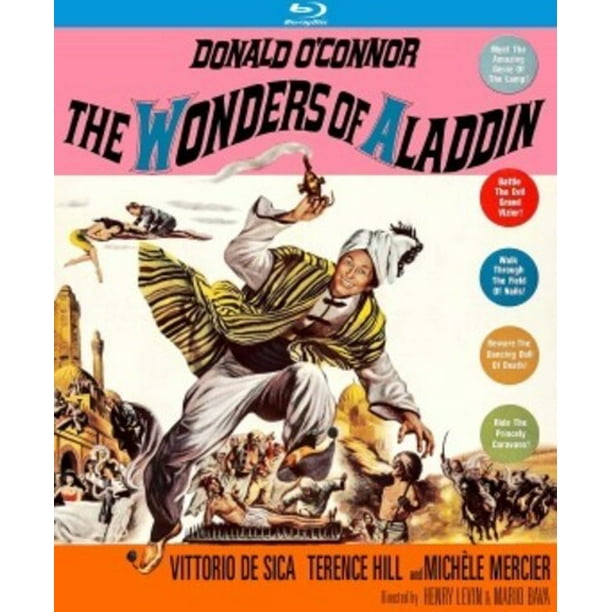

By way of contrast, what about The Wonders of Aladdin (1961), also in Technicolored Cinemascope, now on Blu-ray from Kino Lorber, which mysteriously turned up in my mail uninvited? I missed it on first release, being away at boarding school at the time (where I was being introduced to the arts of Eisenstein and Welles, not to mention Faulkner, O’Neill, and Dos Passos), so seeing it for the first time at age 77—or, more precisely, trying to—is a different matter entirely. Frankly, I couldn’t find any reason to keep watching this; even after learning that an uncredited Mario Bava co-directed it (along with the credited but less auteuristically fashionable Henry Levin), and factoring in my preferences for Aladdin’s Donald O’Connor and Vittorio De Sica over Hajji Baba’s John Derek and Thomas Gomez, I’d still rather put up with the Weis film’s MGM chorus-line glitz (as skillfully imitated by Walter Wanger and Allied Artists) over slapstick peplum and tatty special effects. And the Italian dubbing doesn’t exactly win me over either. I guess it’s my cultural conditioning, some version of which we all have.

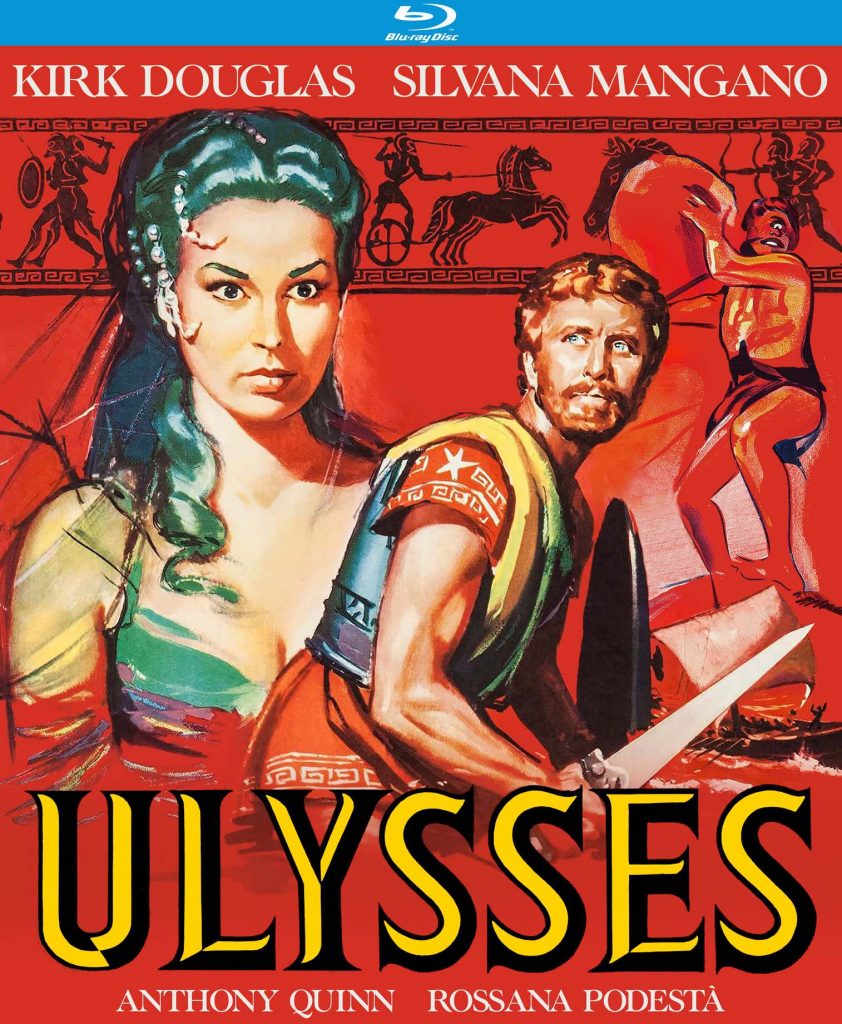

On the other hand, my current interest in Mario Camerini’s Ulysses (1954), a Blu-ray of which arrived in the same package from Fox Lorber as The Wonders of Aladdin, is strictly auteurist (or, to be more accurate, would-be auteurist), even though I also saw and moderately enjoyed this frisky romp in the mid-’50s. Yet it seems that neither of the auteurs I choose to relate it to—Orson Welles and Ernest Borneman—get mentioned anywhere in the package, which is unsurprising when one considers that my own source for knowing their involvement in the film is fairly esoteric and specialized. Based on my sampling of his audio commentary, Tim Lucas has an impressive knowledge of Italian cinema during this period (which was already on display in his magazine Video Watchdog), and I’m sure this must inform his 1,128-page book Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, which has apparently become such a collector’s item since its release in 2007 that Amazon charges $995.98 for a hardcover and AbeBooks over three times as much. (Incidentally, Lucas also has an audio commentary on The Wonders of Aladdin.) But even though he lists and discusses all seven of the film’s credited screenwriters (not counting Homer)—Camerini, Franco Brusati, Ennio De Concini, Hugh Gray, Ben Hecht, Ivo Pirilli, and Irwin Shaw—he doesn’t seem to know that Borneman was originally commissioned to write a script by Welles (when the latter was busy chasing after Lea Padovani in 1947) that served as the basis of the Camerini film years later. To learn about the Borneman-Welles script, you have to go to pages 256-257 in the informative afterword to The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor, a 1937 mystery novel by “Cameron McCabe”—i.e., Borneman, writing his first novel under a pseudonym. (This afterword, incidentally, is the most detailed English-language account of Borneman’s peripatetic career that I know of that doesn’t cost at least $95—which is the price of Detlef Siegfried’s Modern Lusts: Ernest Borneman: Jazz Critic, Filmmaker, Sexologist, published earlier this year.)

Hiring Borneman in Paris to script “a feature about Homeric Greece” because of his “knowledge of pre-classical Greek,” Welles initially accepted the author’s extravagant challenge to make this a Welles feature derived from the Iliadas well as the Odyssey, and invited Borneman and the latter’s wife and son to share his palatial digs in Italy while writing it, a few weeks before Welles went broke and promptly disappeared. Borneman finished the script anyway, then sold it to Carlo Ponti and Dino De Laurentiis, who co-produced the Camerini feature five years later. While none of this should imply that Borneman deserved a screen credit for the 1954 Ulysses (he conceded that his work was “totally altered”), some intriguing traces of his script remain in the final film. Borneman had stipulated that, because Homer used the same adjectives for most of his women characters, the same actress should play them all—which presumably resulted in Silvana Mangano playing both Penelope and Circe. Another part of Borneman’s conception was that all the women should be played by a Black actress, and this led him to introduce Welles to Eartha Kitt, whom Borneman knew from his stint as a jazz musician; this resulted in Welles casting Kitt in a touring show called Time Runs… that played in Paris and many German cities.

***

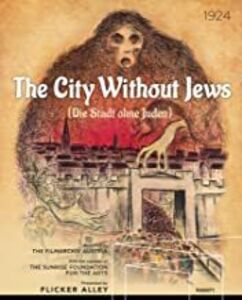

If the 1924 Austrian allegorical satire The City Without Jews—which was restored in 2015 after having been thought lost for over seven decades, and recently released in dual-format by Flicker Alley—had an “auteur” at the time of its original release, this might have been the best-selling author of the eponymous source novel, Hugo Bettauer, who wasn’t happy with the way his work was cautiously watered down. (For starters, “Austria” in the original became “Utopia” in the movie.) According to one of the informative articles included in the Flicker Alley release’s 24-page booklet, this was the fourth of Bettauer’s novels to be adapted into a film; the fifth, G.W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, appeared in 1925, the same year that Bettauer was murdered by a former Nazi party member because of his campaign against anti-Semitism. On the other hand, even though Hans Karl Breslauer, the director and co-writer of The City Without Jews, retired from filmmaking after this feature to launch a career as a fiction writer and journalist, he had previously directed (and sometimes wrote) at least 17 previous features—which is another way of saying that he might have been an auteur by today’s standards, if we had more of his films to look at.

On the basis of this film, however, Breslauer doesn’t appear to have been particularly stylistically inventive, apart from a bizarre Caligari-esque set that turns up near the end. Otherwise, apart from the film’s undeniable and prescient interest as a historical curiosity, the grotesque slapstick depiction of all the characters, Jews and anti-Semites alike, raises the issue of whether the blame for this rests on the Austria of 1924 (whose resemblance, in the film, to Trump’s imagined cartoon kingdom is hard to ignore), Breslauer, Bettauer, or maybe on all three—a question worth raising, but not within my capacity to explore.

For the past half-century—ever since seeing The Edge (1968) one edgy night in Manhattan, and ruminating on its resemblances to Jacques Rivette’s Paris nous appartient (1961) in its haunting alternations between paranoia’s symmetries and the sheer messiness of daily life—I’ve been periodically revising my shifting and unstable sense of Robert Kramer as an auteur. And for about 40 of those years, I’ve been hoping to see an English-subtitled version ofKramer’s Guns (1980)—which stars one great Rivettean actress (Juliet Berto) and co-stars another (Hermine Karagheuz) alongside Patrick Bauchau, the male star of Wim Wenders’ 1982 The State of Things (my favourite Wenders movie as well as the most Rivettean), which was co-written by Kramer and made during the same period as Guns. Re:voir has now fulfilled that wish, with subtitles in no less than four languages, in a gorgeously designed single-DVD package that also includes two Kramer shorts made for French TV in the ’80s and a bilingual 56-page booklet with heavy-duty texts by Kramer, Richard Copans (one of the film’s cinematographers), and Dominique Païni. Better yet, this is only Volume 4 in Re:voir’s unfolding series of ten DVDs devoted to Kramer’s oeuvre (which Jerry White previously wrote about in Cinema Scope 83).

I’m still uncertain about what kind of auteur Kramer was, and how much his co-founding of the militant filmmaking collective Newsreel in the US and his subsequent move to Paris changed his artistic identity. But regardless of how much Guns, a bilingual film reflecting both sides of this dichotomy (documentary drift and decorous precision), “works” or not as a commercial thriller, this is the first Kramer film I can recall that affords very much sensual pleasure in its images, sounds, and performances. The absence of such pleasure is what, for me, separated his many shots of people seated at tables or filmed full-figure in long shots from Rivette’s, and distinguished the grubbiness of his Ice (1970) from the swank beauty of Godard’s Alphaville (1965), even though his own commanding presence and voice as an actor in some of his own films (including Guns), as well as a few by others, has been more of a constant. As a writer-director, his shifts between wanting to convey raw and simple actuality and wanting to employ attractively complicated rhetoric can probably be found in every Kramer feature I’ve seen, but I notice it far more in Guns and in his lovely 1994 essay film about Vietnam, Point de départ, which may be why I tend to prefer these two. But he continues to confound me when, in Guns, he uses Rivettean actors in ways that are virtually the opposite of how Rivette did—opting for a realistic as opposed to phantasmatic Berto and an exotic as opposed to ordinary Karagheuz—or when, as in The State of Things, he deliberately sets about creating an industrial espionage thriller that wanders.

***

Claire Denis’ Beau travail (1999) is also clearly and unambiguously an auteur film. Yet so many other treasured auteurs flavour the mix—among others, Herman Melville, Jean-Luc Godard, cinematographer Agnès Godard (no kin), co-writer Jean-Pol Fargeau, choreographer Bernardo Montet, actors Denis Lavant, Grégoire Colin, and Michel Subor, Benjamin Britten, and maybe Sergei Eisenstein—that it becomes hard to identify the film’s auteur independently of them, because it’s Denis’ taste in using them and determining how to use them that comprises her indelible signature. Like Godard (Jean-Luc, not Agnès), Denis (Claire, not Lavant) is a manic cross-referencer, and because she belongs to the same cross-referencing generation as me (she’s only three years younger) we grew up with many of the same initial signposts, even if these were on separate continents and perhaps delivered in separate languages. This shared history and taste forms a large part of what I appreciate about the wonderful extras on the Criterion Blu-ray, by critics (Judith Mayne and Girish Shambu) and well as collaborators (Colin, Godard, Lavant). Best of all, someone had the great idea of videotaping the writer-director in conversation with Barry Jenkins.

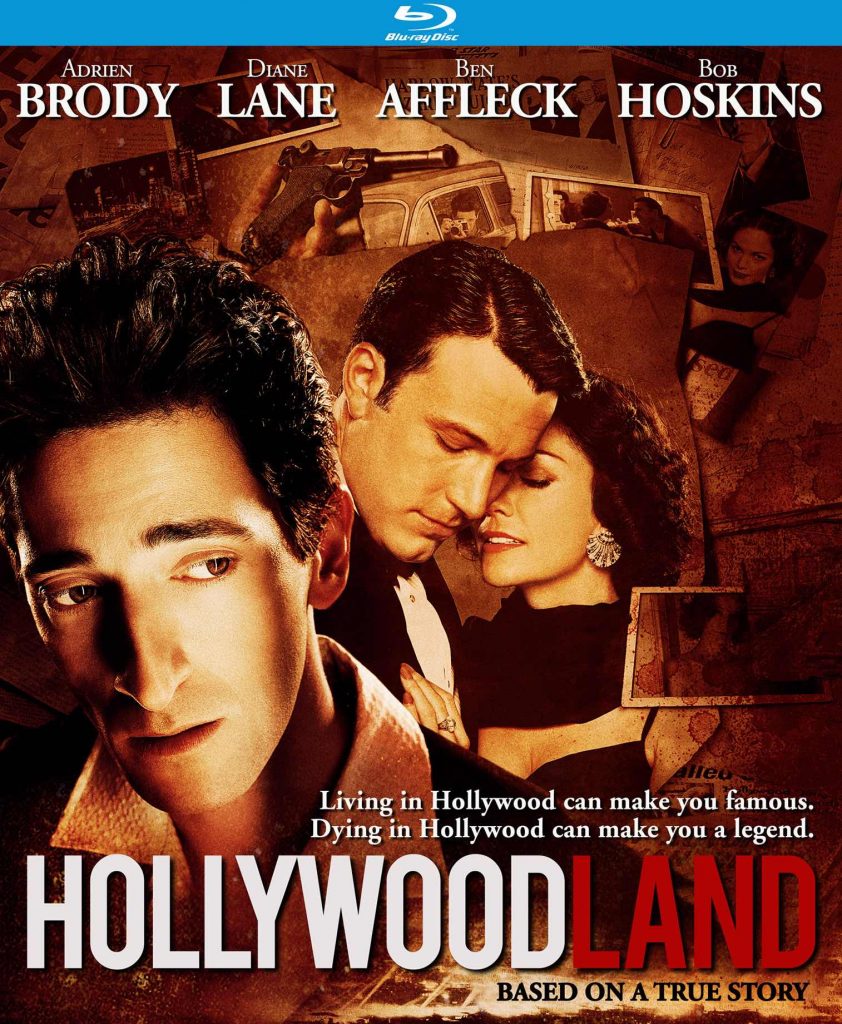

In conclusion, allow me to ponder the strengths and limitations of the auteurist credentials and the newsworthy relevance of two other recent arrivals in my overstuffed mailbox: a Universal DVD of Kitty Green’s 2019 fiction-feature debut The Assistant (a film I saw last year on the big screen and admired, but then promptly forgot), and a Blu-ray, again from Kino Lorber, of Hollywoodland (which I saw and praised as a reviewer in 2006 but only vaguely remembered). The first and timelier of these is not nearly as enjoyable as the latter, but it has a fine beginning that, like Mommie Dearest (1981), suggests one of Universal’s early-sound horror pictures. In the yawning dead of night, the dark hour of the wolf, a dimly perceived heroine moves from her urban home to the back of a car—only in this case, it’s not Faye Dunaway’s Joan Crawford proceeding to a Hollywood shoot, but the ignored assistant of a movie tycoon who is moving from Brooklyn to Manhattan (in a dazzling ride, by the way, the film’s only moments of beauty). The tycoon is said to be based on Harvey Weinstein, as the film was planned around the time that Weinstein’s multiple sexual abuses were becoming better known (and the fact that the character is kept offscreen matches the fact that Weinstein is now in prison), but I think that Green’s film—which shows us a typical workday of one of the tycoon’s mousy assistants, inflected with some Jeanne Dielman touches showing how routines can become ritualized), becomes much timelier if one connects all the bowing and scraping with the autocrat in the White House, who has so far evaded prison and continues to solicit all the reverence and deference he demands.

We should recall that before Janet Maslin got belatedly taken off the New York Times’ movie beat, Weinstein remained the paper’s favourite film critic (with David Thomson running a close second), which may help to explain why the paper also became one of the enthusiastic corporate sponsors of Sundance, with its successful Weinsteinian agenda of pushing major-studio and press-agent interests under the fake banner of independence—an allegiance it has never revised, even after Weinstein went to jail for his activities as a sexual predator. To all appearances, Weinstein’s concurrent activities as a capitalist censor (by recutting films and withholding many from release after acquiring their distribution rights) were approved and even celebrated with the same devotion that Republicans have shown towards the US’ second show-biz president employing the style of a snake-oil salesman—moving up the aesthetic ladder from Bonzo to wrestling in terms of what it’s hawking, which turns out to be the only “art” that can truly be described as “beautiful.”

Is Kitty Green an auteur? I’d have to see her documentaries before hazarding a guess, but I suspect the only real auteur in The Assistant may turn out to be the absent boss who calls all the shots, just as Trump is still the de facto organizer of much of the daily space and drama of anti-Trump media. By contrast, the writer and director of Hollywoodland (Paul Bernbaum and Allen Coulter, respectively) are both TV series veterans, which suggests that their old-fashioned storytelling skill has a lot to do with forsaking personal touches altogether. The timeliness here can be found in the premises that media defines everything (including truth and its absence) and everything is corrupt, but you can’t blame it all on Louis B. Mayer.

In short, there aren’t any offscreen villains here to organize the action; even Eddie Mannix, reportedly a bit of a thug in real life as an MGM executive, comes across more like a sweetie-pie in Bob Hoskins’ performance. What we have instead are two flawed, also-ran hero-victims, the “real” actor who played Superman on TV and hated it (Ben Affleck) and the mostly fictional grubby detective (Adrien Brody) who tries and fails to prove that his apparent suicide was a murder. The movie puts them both in the present tense (i.e., 1959 and today) and implies that winning and losing are two dubious versions of the same dubious activity, As James Naremore has pointed out, this is compassionate post-noir, which virtually amounts to a contradiction in terms. “Forget it, Jake—it’s reality,” one might say, which is perhaps why I mostly prefer this sad, sweet tale to Chinatown.