From the Chicago Reader (November 13, 1992). — J.R.

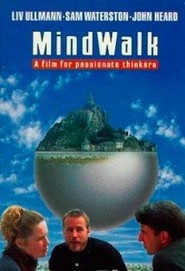

MINDWALK

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Bernt Capra

Written by Floyd Byars, Fritjof Capra, and Bernt Capra

With Liv Ullmann, Sam Waterston, John Heard, and Ione Skye.

Made two years ago, Mindwalk is finally arriving in Chicago (at Facets Multimedia for a week), after having been announced and then withdrawn as an attraction at the Fine Arts many months ago. However, the surprise isn’t so much that the movie is turning up here late as that it’s turning up at all. In this virtual talkfest about Serious Matters set on Mont-Saint-Michel — the islet in the English Channel a mile off the coast of France — three people discuss the state of the world over the course of an afternoon. An American senator (Sam Waterston), a conservative Democrat who has just done poorly in a presidential primary, has gone to visit an expatriate poet friend (John Heard), and the two of them meet by chance a disillusioned European-born physicist (Liv Ullmann). She does most of the talking while they all walk around Mont-Saint-Michel; the two men chiefly ask questions and occasionally offer a skeptical rejoinder or corroborating gloss. The only other character of any importance is the physicist’s daughter (Ione Skye).

The standard industry line about movies like this one is: If you’ve got a message, try Western Union. The problem with this message is that it’s almost invariably applied to movies with liberal or leftist leanings; I’ve never heard anyone voice such a sentiment about Triumph of the Will or The Green Berets or The Exorcist or Fatal Attraction or Pretty Woman, to cite only a few examples of movies teeming with reactionary messages. Indeed, the last three are commonly regarded as “pure” entertainments, without ideological agendas of any kind.

I don’t mean to suggest that Mindwalk is necessarily or exclusively political, though many of its remarks are addressed to a politician. The physicist delivers most of the film’s “message,” which has to do with conceptual and philosophical issues surrounding the survival of the planet and the welfare of future generations — concerns that certainly have political ramifications, though the film brings them up only to establish that there are no ready-made answers. (By making one of its characters a Democrat and a conservative, Mindwalk seems to be hedging its bets on politics.) The closest the film comes to taking a specific political position is when we learn that the physicist left a lucrative position in the United States after discovering that one of her best research ideas was being used in the Star Wars program.

It says a great deal, however, about the estrangement of mainstream movies from politics that the term I’ve been hearing in conversation with my colleagues to describe Mindwalk is not “political” or “ecological” or “philosophical” but “new age,” a term that in this context is not only dismissive but largely misleading. It’s true that the score is a cello piece by the insufferable Philip Glass and that we hear the word “holistic” a couple of times, but surely that’s not enough to justify calling the movie new age.

I think what irritates a good many people about this movie — even when they haven’t seen it — is that it has the brass to consider talk about weighty matters a form of action and the proper subject for a picture. Of course My Dinner With Andre made the same assumptions over a decade ago, but despite some superficial similarities the films are quite different.

My Dinner With Andre starred two people who were real friends, playing only slightly fictionalized versions of themselves — playwright-actor Wallace Shawn (who wrote the screenplay) and stage director-actor Andre Gregory. At the heart of their talk were the philosophical differences between Gregory’s new-age adventures and Shawn’s earthy skepticism about them. The consumerist backdrop — the two are eating a gourmet meal at an expensive New York restaurant — merely gives the conversation a more casual, less didactic tone. The main bill of fare was the juxtaposition of their two worldviews, not a prescription for rethinking global problems; the ambience was that of a theatrical entertainment, not an earnest effort to change the world.

Moreover, while Mindwalk has already attracted a following in other cities (I’m told it’s done quite well in both Los Angeles and Minneapolis), it hasn’t gotten anything like the large-scale promotion My Dinner With Andre received, which was probably crucial to that film’s eventual success. (In Manhattan it was given free screenings with wine and cheese, and the rave reviews it got from the New York Times and the New Yorker were less than surprising given that Shawn is the son of the New Yorker‘s then-editor.) By contrast Mindwalk has received a “national release” without fanfare of any sort.

The Mindwalk project evolved over nearly a decade. It started out as a documentary adaptation by Bernt Capra for BBC television of his brother’s 1982 book The Turning Point: physicist Fritjof Capra wrote about the interdependence of biology, medicine, economics, art, physics, and other fields and about the “crisis of perception” affecting all these areas. For a while Bernt Capra, who had a background in architecture and movie set design (he worked on such features as The Last Tycoon and the remake of King Kong), wanted to set the film in an imaginary building created through special effects, with each room illustrating a separate phase of the argument. This plan was eventually rejected when it was decided it would compartmentalize an essentially holistic philosophy.

In its final form the script, authored by the Capra brothers and Floyd Byars (who worked on Maria’s Lovers, Desperately Seeking Susan, and Making Mr. Right), was consciously modeled on Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, a 17th-century work of fiction designed to promote Copernican ideas, staged as a dialogue between three scholars in a Venetian palazzo. Mont-Saint-Michel was eventually selected as a setting because it provided certain natural metaphors and other reference points — a cemetery, an ancient clock, a torture chamber, a church and church organ, the tides.

The foregoing must make Mindwalk seem terribly pretentious and heavy-handed, but I found it entertaining and absorbing, and far from heavy next to Woody Allen’s ponderous “serious” pictures.

The physicist’s discussion begins with an exposition of Cartesian thinking — with Descartes’ mechanistic view of the world and nature, a model she compares to the workings of a clock. She argues it’s no longer applicable to the world today: such contemporary problems as the deaths of children in the third world and Brazil’s destruction of its rain forests, as well as the contamination of the English Channel and the popularity of red meat, all arise from the practice of treating problems in isolation from one another. Turning next to the subject of light and matter, the physicist delves into probability patterns and the exchange of matter and energy between people and objects. She describes a visit she made to Hiroshima ten years earlier, then the two men recall meeting at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. This eventually leads to the physicist’s extended meditation on systems theory, a “theory of living systems.”

Throughout the conversation the senator tries to reconcile or adapt these theories to his own political agendas, and the poet offers a few poetical commentaries or quotations (with particular attention to Pablo Neruda and William Blake). There are some recurring references to the physicist’s inability to relate to her own daughter, as well as discussions about patriarchy, evolution, and the possibility of pure science, among other things. It’s a tribute to all three actors, Ullmann in particular, that they manage to keep most of this compelling and believable, in terms of both drama and argument. (Perhaps the only serious exception is Heard’s lengthy recitation of a Neruda poem, which stops the story cold in order to bring the argument to a climax.)

But ironically, though the discussion is fluid and lucid and the setting provides graceful illustrations, the film’s form is far too conventional for its radical concepts. This is not to say that a departure from the narrative — something like the free-form abstract passages in Errol Morris’s A Brief History of Time — would have been appropriate; indeed, when these filmmakers use characters’ voices offscreen at the beginning and end of Mindwalk to add personal commentaries, the device is more awkward than edifying. (This is Bernt Capra’s first effort as a director, and sometimes it shows.)

Like Morris, the filmmakers have taken on the task of making difficult concepts comprehensible in a mainstream movie, and although they carry out this work at least as well as Morris does, they have to depend on a good many old-fashioned film conventions — none of which we’re supposed to be thinking about — in order to accomplish that task. The biographical facts about the characters that keep intruding here (as they do in the Morris film) resemble the kind of political concessions and compromises the physicist and senator keep bringing up — that is, they dilute the “message” while allowing it to be heard and understood.