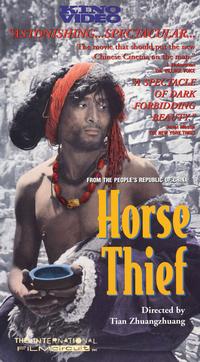

I truly regret not being able to illustrate this early piece for the Reader, published in September 1987, with the sort of illustrations its awesome landscapes deserve. In fact, the only other film by Tian Zhuangzhuang (see photo above) that I’m aware of that’s comparably impressive from this standpoint is his extraordinary Delamu (or, in Chinese, Cha ma gu dao xi lie), a 2004 documentary that’s even more neglected, at least in this country (see the photo below, immediately after the absurdly small landscape photo from The Horse Thief).[2023 postscript: Happily, illustrations are now more readily available, and even though the film doesn’t seem to be currently available on DVD or Blu-Ray, it can be seen letterboxed and subtitled in all its widescreen glory at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZSjjOQUtHY.] –J.R.

It’s worth adding that one can now obtain The Horse Thief inexpensively, letterboxed and with English subtitles, at www.yesasia.com/us/1005182257-0-0-0-en/info.html. And see the previous link for a Blu-Ray.–-J.R.

THE HORSE THIEF

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang

Written by Zhang Rui

With Cexiang Rigzin and Dan Jiji.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

If the two aesthetically richest decades in the history of cinema have been the 1920s and the 1960s, it is in no small part due to the fact that it was during these two golden ages that film came closest to becoming a universal language. Some recent film theorists, arguing that film images are dependent on linguistic structures, have denied the claims for silent film’s universality. But the fact remains that the consolidation and purification of silent film language in the 20s coincided with an international film culture where cross-pollination seemed almost the rule rather than the exception.

The same impulse toward internationalism that led to shop signs in Esperanto and a virtual absence of intertitles in the very influential The Last Laugh (1924) also turned most of the giants of this period–Chaplin, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Flaherty, Griffith, Lubitsch, Murnau, Sternberg, and Stroheim, among others–into a race of globe-trotters. “Fair exchange isn’t robbery,” Art Blakey recently pointed out at the Chicago Jazz Festival, referring to the mutual education that passed between him and his various sidemen over the years. The same could be said of those periods in film history when countries are most open to ideas from abroad.

The second golden age came about largely through the efforts of a new generation of directors to reapply some of the lessons of the 20s and forge another international film culture. Films as diverse as Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Hatari, Breathless and Blow-Up, The Savage Innocents and Fahrenheit 451, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Playtime, Contempt and The Rise of Louis XIV were virtually defined by their multinational elements and sentiments; and for the first time since the 20s––barring perhaps only the impact of Italian neorealism in the 40s–Hollywood styles of filmmaking were fundamentally overturned by new developments from abroad. (Some of the most banal tropes of current movies–such as ending a film with a freeze-frame––can be traced back directly to the innovations of this period.)

If one adopts a cyclical theory of film history, the next golden age of internationalism will be the first decade of the next century. Director Tian Zhuangzhuang has said that he made The Horse Thief for the 21st century, and one wonders if he might have had some of this internationalism in mind. For the power of this breathtaking spectacle from the People’s Republic of China, which is receiving its U.S. premiere at the Art Institute’s Film Center this Saturday and next Friday, is to a large extent its capacity to communicate directly, beyond the immediate trappings of its regionalism and culture, not to mention its nationality and its period. The relatively small role played by dialogue and story line and the striking uses of composition and superimposition make it evocative of certain films of the 20s, although it is anything but a silent film: the chants, percussion, and bells of Buddhist rituals and the beautiful musical score that incorporates them form an essential part of its texture. And the film’s bold uses of color and a rectangular ‘Scope format, as well as its mesmerizing camera movements and very eclectic style of editing, make it more readily identifiable with movies made in the 60s.

Set in the remote wilds of Tibet, with a cast consisting entirely of Tibetan nonprofessionals, The Horse Thief concerns a man named Norbu, an occasional horse thief who is eventually expelled from his clan for stealing temple offerings. Living in isolation with his wife Dolma and his little boy Tashi, he periodically returns to the tribe’s temple to pray, and appears to be genuinely remorseful about his crime, particularly after his son dies. But after two more harsh winters, and the birth of another son, he finds it necessary to steal again in order to keep his family alive, and even kills a sacred ram. After he is told by an old woman of the clan, who may or may not be his grandmother, that his wife and child can return, but that he is “a river ghost, full of evil,” he steals another couple of horses and sends his family back to the clan on one of them.

These are the bare bones of the plot, or as nearly as I’ve been able to make them out, but they are far from adequate as a description of the film, even as narrative; it is implied, for example, that Norbu dies at the end of the film, but whether in fact he does is not made explicit. Basically a film about the harshness of a terrain and a climate, and the continuity of Buddhist death rituals, this is in certain respects scarcely a narrative film at all. Significantly, it was only during a third viewing of the film that I focused on the plot. That viewing yielded the partial synopsis given above, but didn’t convince me that it brought me face to face with what the film was like or about in any definitive sense.

Tian is a member of China’s so-called “fifth generation” of filmmakers––those who entered the Beijing Film Academy after the end of the Cultural Revolution and began to have access to a wide range of films from abroad. According to Alan Stanbrook in Sight and Sound, Tian and his former classmates, including Chen Kaige (Yellow Earth), Huang Jianxin (The Black Cannon Incident), and Wu Ziniou (The Last Day of Winter), were “weaned on directors like Godard, Antonioni, Truffaut and Fassbinder, though the current batch of students shows little interest in these filmmakers, or, indeed, in the work of previous graduates like Chen Kaige and Tian Zhuangzhuang,” preferring to study the films of Hitchcock and Spielberg. What this latter focus will lead to is uncertain, but I would wager that it could not produce a film remotely like The Horse Thief.

The films of the 1982 graduates of Beijing are only beginning to be circulated in the West, and in certain cases their exposure in China has been limited as well. While anywhere from 100 to 300 prints are usually struck for a new Chinese feature, only 11 were made of The Horse Thief, while a mere two were made of On the Hunting Ground, Tian’s only previous feature; print runs of Exile of a Folk Artist, his latest film, which is apparently designed to be less controversial, have not yet been reported. Another identifying trait of this group is that their films are made at the Xi’an film studio, presided over by Wu Tianming––in contrast to the more conservative and traditional films produced at Wu Yigong’s Shanghai studio.

Before being released, The Horse Thief suffered two kinds of censorship at the hands of government authorities. One of these was an addition rather than a subtraction––the date “1923,” which flashes on the screen before the first image, thus locating the action in a specific period rather than making it more timeless, which was the director’s intention. (On the whole, acknowledging my sketchy acquaintance with Buddhism and Tibetan history, there is nothing else in the film that could squarely place it even in this century; apart from the use of rifles in one or two scenes, there are practically no forms of technology present to date it at all.) The other form of censorship was the elimination of corpses from the first of three separate “sky burials” in the film, when human bodies are fed to carrion birds. We do in fact see these birds feeding on flesh–they appear at the beginning of the film, in the middle, and again at the end (when perhaps it is Norbu they are devouring)––but evidently the original version was more explicit.

All three of Tian’s features are concerned with minority cultures within China; On the Hunting Ground is set among the herdsmen of Inner Mongolia, and Exile of a Folk Artist, according to Stanbrook, is “about the folk singers and artists who fled from the Japanese during the war of resistance and ended up in south-west China.” It would appear that some of the difficulties he has had with his first two features stem from what might be considered the brutality of the cultures shown. On the Hunting Ground, I am told, is fairly explicit about the slaughter of animals, and after The Horse Thief received its first showing in the West early this year––at the Rotterdam Film Festival, where I first encountered it––it was initially held back from export because Chinese authorities reportedly felt it fostered a falsely primitive impression of the nature of Tibetan life.

Personal to a degree which seems anomalous in a Chinese Communist context, The Horse Thief clearly cannot be reduced to an ethnographic study or a travelogue. One might assume that a plot so slender would be shaped like a parable to drive home a particular point; if that is the intention of this film, which I tend to doubt, it is a point that eluded me. The difference between isolation and community is obviously part of what the film is about, but even this concern seems often dwarfed by the dominance of the landscape and the sounds of the Buddhist rituals, which make this difference appear almost irrelevant. (In this respect, it is worlds apart from Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents, about Eskimo life, in spite of certain visual and behavioral resemblances.) Composed mainly of short sequences connected to one another by quick fade-outs or slow lap dissolves, the film offers itself almost entirely as spectacle, and as such seems to be structured more on musical terms than on narrative ones; in this framework, Norbu figures less as a theme than as a solo instrument that occasionally rises above the ensemble passages––plaintive in its isolation, yet never divorced from the surrounding musical context.

The musical sensibility is apparent in the recurrence of certain locations, sounds, and camera setups; in the lightning-quick shot of the collapse of a tent, effected by Norbu’s accomplice in the first horse theft that we see; in a remarkable sequence devoted to Norbu’s extended praying and prostrations, which hypnotically combines camera movements and superimpositions with a use of other human figures that ambiguously alters our sense of his isolation; in the slow drip of water from melting snow that Norbu catches in a jug to bring to his ailing child; in the intricately structured sequence showing the clan’s westward migration, as fine a piece of epic poetry as some of the grander collective movements in Ford; and above all, in the depictions of the Buddhist ceremonies and rituals, which are themselves patterned like musical structures. And despite the highly formalized nature of Tian’s visual style and rhythm, the flow of a given sequence never becomes predictable: an unexpected low or tilted camera angle, all the more jarring in a ‘Scope format, will suddenly veer a scene’s progress in a different direction; or an unforeseeable shift in the camera’s distance from a subject will bring about a similar reorientation.

In short, the relative paucity of plot is never experienced as an absence because virtually every shot becomes an event in itself. As in 2001, the overall movement of The Horse Thief is toward revelation. The film’s environmental and ecological mysticism, while inextricably tied to Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies, has little of the heavy cultural baggage one associates with the mysticism of Andrei Tarkovsky, or even with the more folkloric mysticism of Alexander Dovzhenko or Sergei Paradjanov, which it more closely resembles. Perhaps where it most sharply distinguishes itself from other films is in its ambiguous juxtaposition of human figures with landscapes; without ever proposing an antihumanistic or even nonhumanistic vision, it nevertheless situates the human in a different relationship to nature. Partaking of some of the universal language imparted to us by the silent cinema of the 20s in its compositional boldness and simplicity, and by the eclectic cinema of the 60s in its awareness and development of this cinematic past, The Horse Thief is a film of the future in more ways than one.

Published on 18 Sep 1987 in Chicago Reader, by jrosenbaum