From Video Movies (August 1984). — J.R.

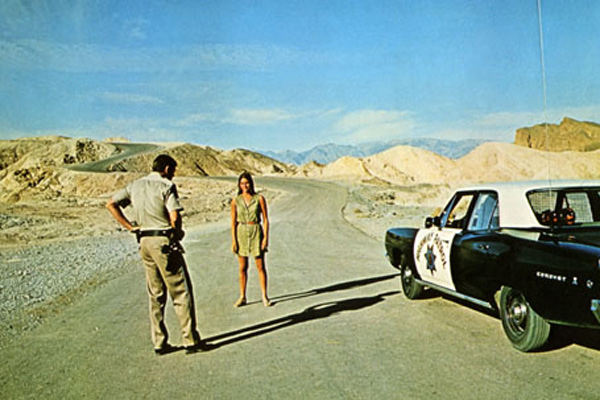

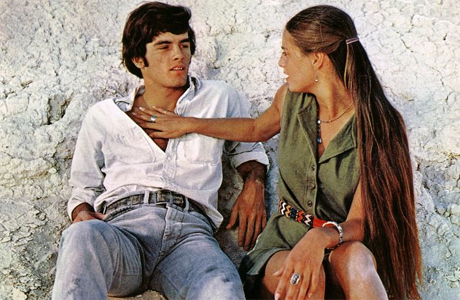

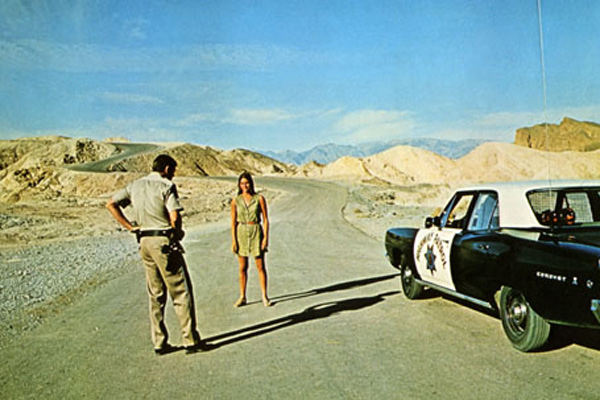

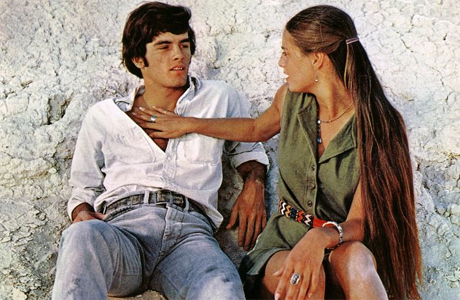

Zabriskie Point

(1969), C, Director: Michelangelo Antonioni. With Mark Frechette, Daria Halprin, Rod Taylor, and Kathleen Cleaver. 111 min. R. MGM/UA, $59.95.

In the 1960s, he could do no wrong, especially after his hit, Blow-up. In the 1980s, Michelangelo Antonioni emerges as a shamefully neglected figure — only one of his last four films (The Passenger) has been released in this country. And Zabriskie Point, the film that virtually destroyed his American reputation, offers ample proof of both the Italian director’s brilliance and his neglect of filmmaking particulars that Americans seemingly will not stand for. To understand Antonioni’s art, we must acknowledge that he is not a storyteller but a composer/choreographer of sounds and images.

As either a plausible romance about disaffected youth or as a documentary rendering of 1969 America, Zabriskie Point is often ludicrous. But if one keeps in mind that Antonioni thinks through his camera more than through his scripts — and that realism is far from his intention — one can see this film as an astonishingly beautiful achievement. As the director noted at the time, “The story is certainly a simple one. Nonetheless, the content is actually very complex. Read more

From the April 1985 Video Times. — J.R.

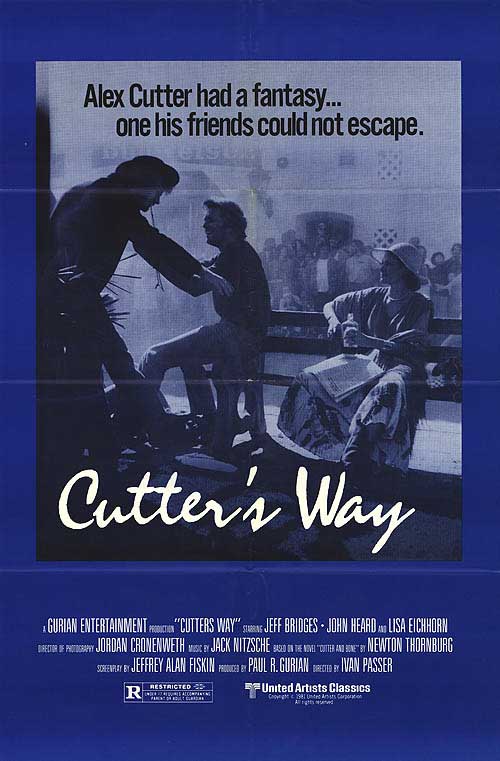

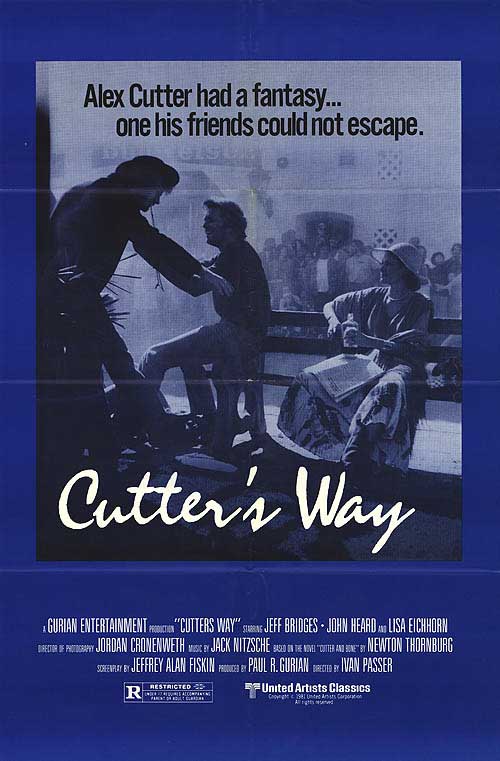

Cutter’s Way

(1981), C, Director: Ivan Passer. With Jeff Bridges, John Heard, Lisa Eichhorn, and Ann Dusenberry. 105 min. R, MGM/UA, $69.95.

A powerful, erotic thriller with remarkable performances from all three of its leads (Jeff Bridges, John Heard, and Lisa Eichhorn), Cutter’s Way never made the impact it should have when it was released. Originally titled Cutter and Bone, after the novel by Newton Thornberg on which it is based, it quickly became a studio write-off in the immediate wake of Heaven’s Gate. Not even a brace of rave reviews and a couple of film festival prizes could save it. Rereleased a few months later as Cutter’s Way, the film went on to acquire an enthusiastic cult that continues to appreciate its sensitive, offbeat mood and its indelible portrait of disaffected America.

The film is tightly scripted by Jeffrey Alan Fiskin and directed by the Czech expatriate Ivan Passer, best known for his bittersweet Czech feature Intimate Lighting, as well as such American features as Born to Win, Law and Disorder, and Silver Bears. Cutter’s Way is an in-depth portrait of the complex relations between three disaffected people. Read more

From The Soho News (November 17, 1981). Ironically, this review was originally copyedited rather clumsily, so I’ve tried to restore some of its original logic and meaning. Incidentally, for those who might be interested, my earlier review of Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature for Soho News can be accessed here. — J.R.

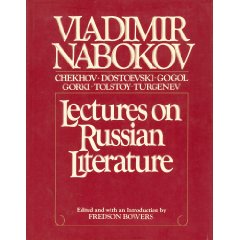

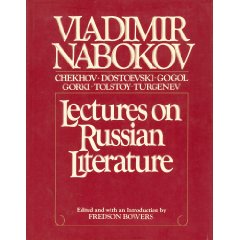

Lectures on Russian Literature

By Vladimir Nabokov

Edited and introduced by Fredson Bowers

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, $19.95

Compare the book under examination to Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature, reviewed in these pages last November. Is Volume II a worthy successor, an arguable improvement, or a distinct letdown? Explain. (Use concrete examples.)

All three. Issued in a uniform edition at the same price, only 50-odd pages shorter -– the jacket Indian-red in contrast to last year’s sky-blue –- the book can be considered a worthy successor. Insofar as it contains meaty selections from what I take to be Nabokov’s supreme act (and work) of literary criticism (not counting his voluminous notes on his translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, which I haven’t read) –- namely, his eccentric and indelible Nikolai Gogol, first published by New Directions in 1944 -– it can arguably be deemed an improvement, even over his exhilarating and enlightening lectures on Flaubert and Kafka in the first volume. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 1, 1991) — J.R.

ARCHANGEL

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Guy Maddin

Written by George Toles and Maddin

With Kyle McCulloch, Kathy Marykuca, Ari Cohen, Sarah Neville, Michael Gottli, and Victor Cowie.

Amnesia is a subject we associate with film noir of the 40s and 50s, and social commentators tend to link its use in such films — with their gloomy and murky moods, their amnesiac heroes’ helplessness — to some version of postwar angst. Now it appears that amnesia — both as subject and as metaphor — is making a minor comeback as a postmodernist theme. An early instance of this trend can be found in the fate of Tyrone Slothrop, the hero of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow, who gradually gets phased out of the book as a visible presence once he starts shifting his attention from his inscrutable, troubling past to his immediate present. We learn that “‘personal density is directly proportional to temporal bandwidth….Temporal bandwidth’ is the width of your present, your now … [and] the narrower your sense of Now, the more tenuous you are. It may even get to where you’re having trouble remembering what you were doing five minutes ago, or even — as Slothrop now — what you’re doing here, at the base of this colossal curved embankment…”

It’s a paradoxical hallmark of postmodernist art to be preoccupied with certain aspects of the past while being closed off — whether through indifference or ignorance or (real or metaphorical) amnesia — to certain other aspects. Read more