From the June 1984 issue of Film Comment. This chronicles my very first visit to the Rotterdam International Film Festival. I believe I was the first member of the American press ever to have been invited (a perk I owe to Sara Driver and Jim Jarmusch having spoken to festival director Huub Bals) — the first of my 20 visits to this very special festival. I’m sorry that Rotterdam no longer invites me (I believe that my last visit there was in 2007), but I guess even the best perks can’t be expected to last forever. My first visit there, in any case, was one of the most memorable; Joseph L. Mankiewicz was there to accept the Erasmus Prize (and to give a press conference at which, if memory serves, he spent almost half an hour answering the first question), and I received my very first glimpses of the work of Raúl Ruiz. I should add that I did festival reports this first year for both Film Comment and Sight and Sound, although it was part of Huub’s singularity that he never required any coverage from me in order for me to get invited back the following year. — J.R.

Split Images

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Americans search for objective truth and believe in reality; Europeans believe in fiction and build images. The distinction might seem facile, but the work of European independent filmmakers compared to that of their American counterparts seems to bear it out.

The 1984 Rotterdam Film Festival is a case in point. The leading filmmakers on display at the festival — Raúl Ruiz, Miklós Jancsó, Sally Potter, Philippe Garrel, and even Wim Wenders, ostensibly presenting a documentary — make the use of the image as a vehicle of fiction their principal concern, with stunning and haunting results. Small wonder that one’s dreams in Rotterdam are more vivid than at other festivals; few others succeed in presenting so many repressed phantoms on their screens.

Of the two dozen films I saw at the festival and the dozen others I sampled, there was surprisingly few duds, half a dozen mindbenders, and a good 20 films of solid interest — an unusually high percentage. Hubert Bals, the festival director, chose well from a wide range of interesting work.

Work on the image; a belief in fiction. Put them together and a bombshell of formal, surrealist, and narrative assault — Ruiz’s City of Pirates — suddenly becomes possible. This Gothic fantasy, shot in riotous color and set on a Portuguese island, runs an affective gamut from Peter Pan and Disney to Anne of the Indies (and from Poe and Lautréamont to Fritz Lang’s Moonfleet and Jacques Rivette’s Noroît without ever seeming derivative — only inspired, singular, perpetually unpredictable, and terrifying beautiful. The film is decked out with astonishing lab effects (painterly long shots of the island, brimming with magical light), unsettling fantasy conceits (a man’s face casually discovered under a pile of vegetables in a trunk), and uncanny spatial displacements. Pirates evokes some of the recollected splendors and sudden transitions of gruesome fairy tales, while enacting a maniacally inventive mise en scène around them.

An inventor, tinkerer, and compulsive worker. Ruiz showed only three of the seven films he’s made during the past year at the festival, but you could swim an ocean between the assumptions and methods of any two of them. The makeshift fictions prompted by French and English parks in the comic short Querelle des jardins — offset by a jiggly camera, an offscreen voice, and a pointing hand — are leagues away from the petulant Beckett-like stammers and absences of a clunky black-and-white conundrum like Point de fuite. [2010 note: In fact, I later heard that this is apparently a color film, but Ruiz was showing a black and white workprint.] The range of these three films is greater than the whole oeuvre of other talented directors. The Edgar G. Ulmer of the avant-garde, Ruiz remains in continuous production by accepting TV commissions of all times, working in several countries and languages, and occasionally letting some aspects of a film (like the defiantly bad acting in Point de fuite) pass uncorrected while he tinkers elsewhere. On the limited evidence of this trio of films, Ruiz doesn’t seem interested in polished masterpieces; it’s invention that keeps him going.

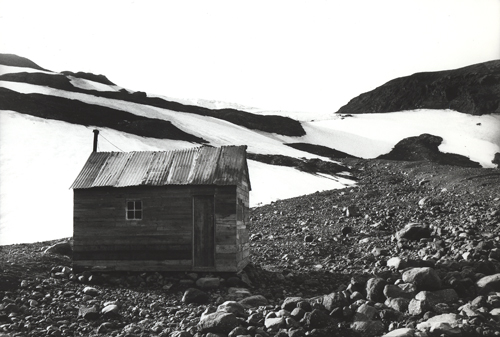

For sheer black-and-white pyrotechnics, Sally Potter’s The Gold Diggers and Philippe Garrel’s Liberté, la nuit both offer superb though distinctly different visual effects. Potter’s allegorical fantasy about gold, money, and women — filmed in England Iceland with Julie Christie and generous BFI production values — is the more striking of the two, thanks in part to Babette Mangolte’s high-contrast cinematography, Rose English’s surrealist art direction, and other diverse contributions from the nearly all-female crew and cast. Plainly an anomaly in relation to the English avant-garde, The Gold Diggers remains proudly unabashed and agreeably witty about its own cosmic pretentions.

As for Liberté, la nuit, a moody memory piece about France during the Algerian War, it quivers like a D.W. Griffith melodrama invaded by the spirit of Rimbaud. Garrel’s camera lingers at length on intense closeups of his father Maurice, Emmanuelle Riva, and Christine Boisson, creating disturbing stylistic ruptures that periodically congeal and disrupt the narrative flow. Another dense aftertaste is offered by Lee Sokol’s Aquí Se Lo Halla, an original American short about sexuality. Sokol intercuts shots of a bullfight, conjuring tricks, and a red scarf moving across a female torso while a Mexican man reminisces offscreen about his teenage crush on a nun at a convent school. A kaleidoscopic narrative effect is achieved with graceful and sensual rhythms.

Charles Burnett’s My Brother’s Wedding presents a fascinating look at life in the Watts ghetto of Los Angeles, in a manner free of polemics and extraordinarily alert to its varied cast of characters. if some of the actors lack a certain professional polish, they more than make up for it in personality, and the film loses none of its charm and power when there is an occasional slippage from performance to presence, as in Renoir’s Toni. My Brother’s Wedding was part of the recent New Directors/New Films series in Manhattan; but it and Burnett’s previous Killer of Sheep have scarcely been seen elsewhere in this country — a situation that is at best a scandal of absent-mindedness.

There’s nothing intellectual about Lothar Lambert’s shoestring Fraülein Berlin, but for flaky fun, this Candide about a German porn actress (Ulrike S.) trying to go straight does offers some fresh and enjoyable outrageous moments. Best is this regard are the raunchy film-world cameos: David Overbey interviewing the heroine about her dog’s sexual preferences; Norman Jewison chatting her up at a Gatsbylike party; Bette Gordon and Tim Burns enlisting her in a hardcore quickie inspired by The Night Porter.

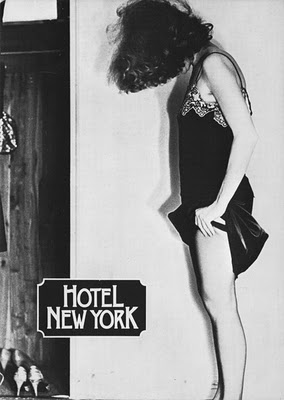

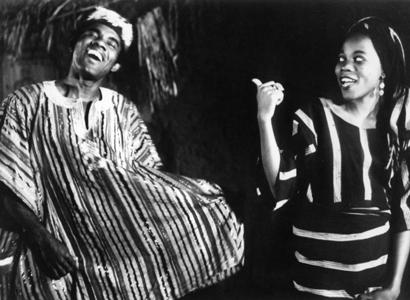

Indeed, some of the more entertaining films in Rotterdam were about filmmakers: feature-length documentaries on Robert Bresson and Joseph L. Mankiewicz (the latter amiably present at the festival for a retrospective); Wim Wenders’ interrogation, in the gloomy, minimalist Room 666, of 15 other directors (from Godard and Antonioni to Paul Morrissey and Steven Spielberg) about the future of cinema; Jackie Raynal’s loony and parodic self-portrait in Hotel New York, which views that city through quizzical French eyes; Férid Boughedir’s Caméra d’Afrique, an interesting survey of African filmmakers; and a tasteless if morbidly arresting bio-pic about Fassbinder, Rader Gabrera’s Ein Mann wie Eva, with Eva Mattes as the reigning Rainer.

One interesting lesson of the festival was how dispensible many of the assumed essentials of filmmaking are. Lothar Lambert does without lip sync, Ruiz eschews auteurist assumptions, Potter and Garrel bypass color, Wenders sticks to a single camera setup, and at no point do these absences register as losses. Rather, they’re essential elements of the achievements of these filmmakers. Freed from the constraints of a literal-minded realism, they use the medium more flexibly and more powerfully, In Rotterdam, with a brlief in fiction, anything is possible.

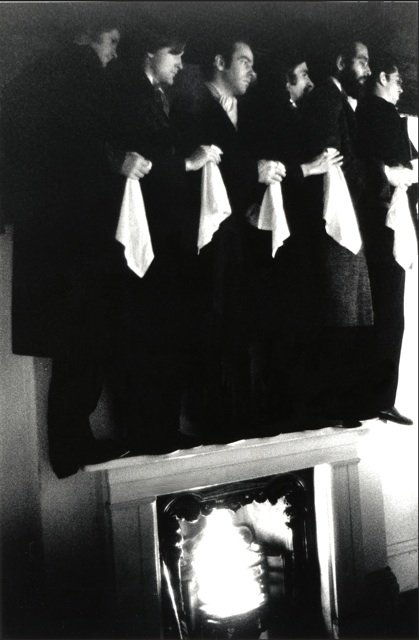

Even quality television. Miklós Jancsó’s Faustus Faustus Faustus, a 450-minute TV serial adapted from a novel covering nearly half a century of Hungarian political and social life, is narrative television of the highest order. If Jancsó’sfilm camera moved like a Matisse crayon through the exterior spaces of Red Psalm, his video camera moves with the fluidity of a genuine caméra-stylo through the interiors and exteriors of Faustus; it traverses years and reflective narrative pauses alike with the supple speed of reading while executing an intricate pas de deux with the voiceover narration, spoken by the Faustus figure. Elegantly scaled for the small screen, the narrative follows faustus’ communist “protégé” from boyhood through middle-age, a somber life framed by the folk saying, “To play the bagpipes well, you must go through hell.”

Rotterdam’s Ten Best: 1. La Ville des pirates. 2. Faustus Faustus Faustus. 3. The Gold Diggers. 4. Liberté, la nuit. 5. Querelle des jardins. 6. Hotel New York. 7. Room 666. 8. Aquí Se Lo Halla, 9. My Brother’s Wedding, 10. Fraülein Berlin.

— Film Comment, June 1984 (tweaked February 2010)