This is the second and final part of an article published in the January-February 1975 Film Comment. — J.R.

Towards an aesthetic evaluation. For critics of the Thirties and the early Forties, Disney was an essential figure in the arts. Eisenstein declared him to be the most interesting filmmaker in America, and over the decade that followed, Erwin Panofsky praised the early cartoons and “certain sequences” in the later ones as “a chemically pure distillation of cinematic possibilities”; Gilbert Seldes offered many sympathetic critiques; and even E.M. Forster published a brief tribute to Mickey Mouse. Lewis Jacobs’ assessment of Disney in The Rise of the American Film is certainly more likely to raise eyebrows today than it was in 1939:

“In the realm of films that combine sight, sound, and color Disney is still unsurpassed. The wise heir of forty years of film tradition, he consummates the cinematic contributions of Méliès, Porter, Griffith, and the Europeans [sic]. He has done more with the film medium since it added sound and color than any other director, creating a form that is of great and vital consequence not only for what it is but for what it portends. He is the first of the sight-sound-color film virtuosos, and the fact that he is still young and still developing makes him an exciting and important figure to watch.”

But by the middle Forties, after the commercial failure of FANTASIA and several government-supported films led Disney to a more mercantile attitude towards his productions, his critical reputation was already on the decline. And by the middle Sixties, one could say that he was more generally regarded as anything but an artist — at any rate, something much closer to Henry Ford than to John Ford — to the extent that Richard Schickel could confidently assert in The Disney Version, without apparent fear of contradiction, that “Our environment, our sensibilities, the very quality of both our waking and sleeping hours, are all formed largely by people with no more artistic conscience and intelligence than a cumquat.”

For Panofsky, Disney’s “fall from grace” occurred when “SNOW WHITE introduced the human figure and when FANTASIA attempted to picturalize The World’s Great Music.” Today this judgment sounds a little too pat, although it is easy enough to see what he meant. It was probably inevitable that once Disney took on the challenge of cartoon features he would come closer to the conventions of non-animated Hollywood films and further away from the relative abstractness and “purity” of the early “Silly Symphonies,” at least in the overall breadth of his films.

But one also suspects that Disney was kept in the Pantheon as long as he remained a novelty, and dismissed as soon as he became commonplace — a ruling that has little to do with the intrinsic worth of his separate films, and a great deal to do with shifting fashions. One might add that the use of the human figure and the musical pretensions of FANTASIA were already implicit in the anthropomorphism and use of music in the earlier cartoons, and a case could certainly be made that what Disney lost in purism he gained in proficiency.

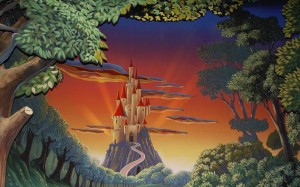

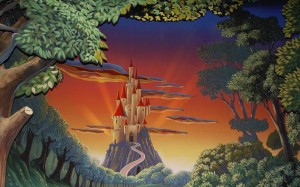

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS is rich with a kind of pictorial beauty that is light years ahead of the crude barnyard effects of the early Mickey Mouse efforts; and it is more than incidentally graced by a score (music by Frank Churchill, lyrics by Larry Morey) that is probably superior to that of any musical released the same year. (1) The fairy-tale castle occupied by the Witch — a lovely construction that seems to combine aspects of Brueghel’s Tower of Babel with a distillation of almost every other storybook dream palace — is so rich in suggestiveness that a near-replica, on which former Disney employees collaborated, wound up serving admirably as Xanadu in the powerful opening shots of CITIZEN KANE: not only the long-shot vista of it standing on a mountain, but virtually the same lap dissolve to an almost identical grilled window in the subsequent closer shot. In a more general way, the water effects in the bottom of a well and in a stream are animated with a translucent brilliance that recalls some of the watery dissolves in Murnau’s SUNRISE, while the throbbing lights and billows of magical smoke in the Witch’s laboratory evoke some of the look of his FAUST.

If SNOW WHITE and PINOCCHIO can be said to take on a related visual aspiration, this appears to be — at least intermittently — a recreation of the silent German “expressionist” cinema in color and sound, simplified, abstracted, and “perfected” to the point where characters are truly continuous with the décor, and actors are no longer strictly necessary, except as disembodied voices for the speaking (or singing) parts. But SNOW WHITE surpasses PINOCCHIO in its stylistic integration of character with character, and of characters with settings. The forest animals are carefully individuated, and yet, like the crowds in METROPOLIS, they often seem to breathe and move — implicitly, feel and think — in a common pulse. The same paradox applies, of course, to the seven dwarfs; they are both a gallery of distinct types and the interworking parts of a continuous organism, like fingers in a fist.

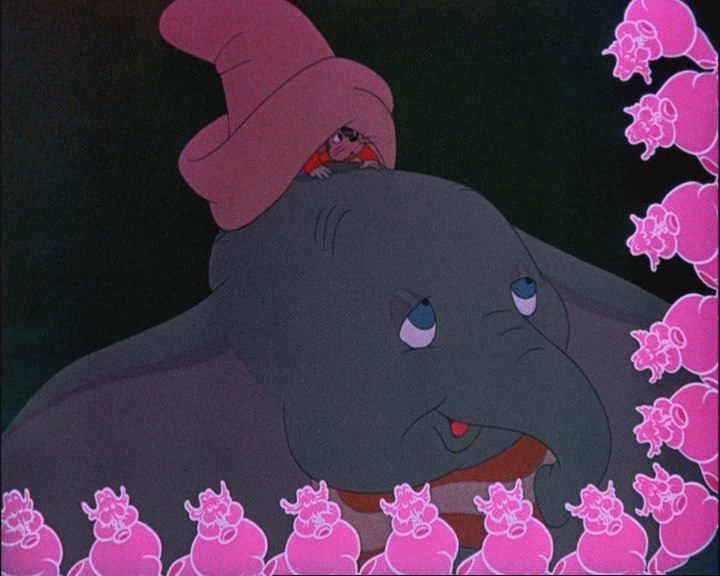

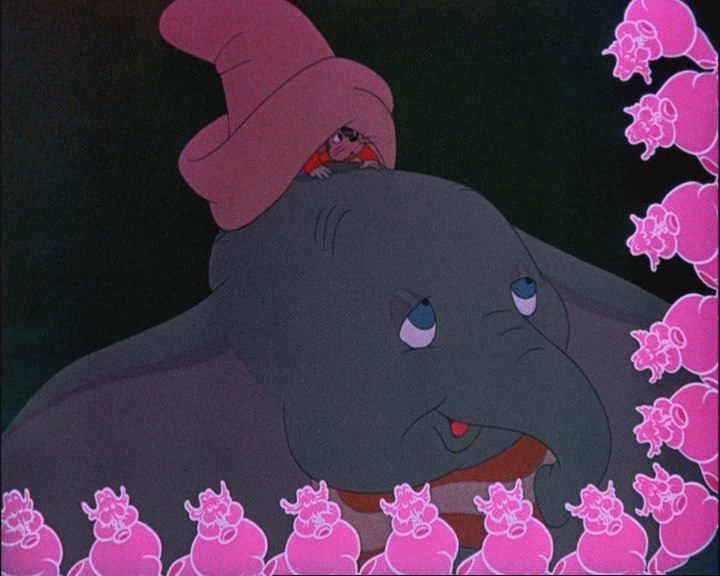

Perhaps the pinnacle of Disney’s pictorial achievement is to be found in the Dance of the Pink Elephants in DUMBO (a film, incidentally, that appeared not long after the alleged decline announced by Panofsky). This prodigious dream sequence, with its continual shifts of color, shape, and scale to match the metamorphoses of dream elephants into a variety of apparitions — beginning as champagne bubbles, and ending as clouds — could probably be stacked against any of the “Silly Symphonies” for formal beauty, purity, imagination, lack of pretension, and its use of music; for its surrealist terror, it even approaches some of the best of Tex Avery. On the other hand, one cannot call the sequence an entirely original one: some of the beasties and their transformations can be traced back to the early sound masterpieces of Max Flesicher.

Nothing else in DUMBO quite equals this, although scenes of a train arriving in a small town at night and a circus tent being erected in the rain have a sullen poetry that unexpectedly evokes some of the paintings of Edward Hopper.There is a tendency for most of the features to break down into separate sequences, from the best (PINOCCHIO, DUMBO, ALICE IN WONDERLAND) to the worst (THE LADY AND THE TRAMP, SLEEPING BEAUTY, THE SWORD IN THE STONE). As Marie-Therèse Poncet and others have noted, FANTASIA is nearly always discussed as a feature when it is in fact a collection of shorts, and this applies to most of the other “feature” cartoons as well. (2)

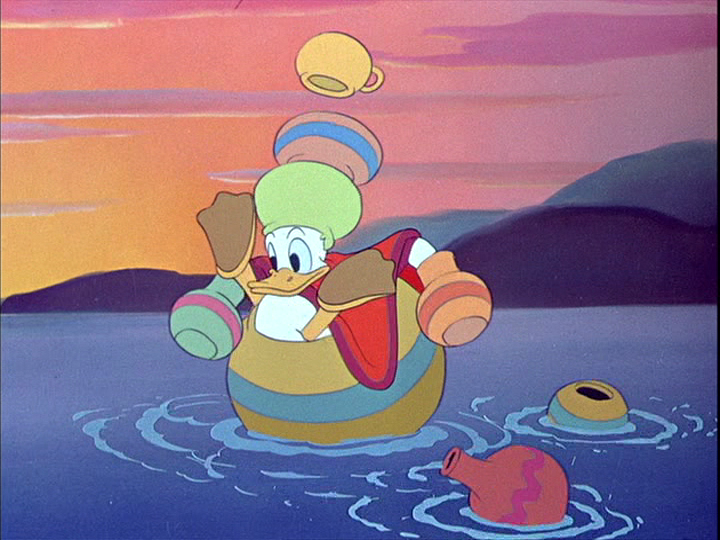

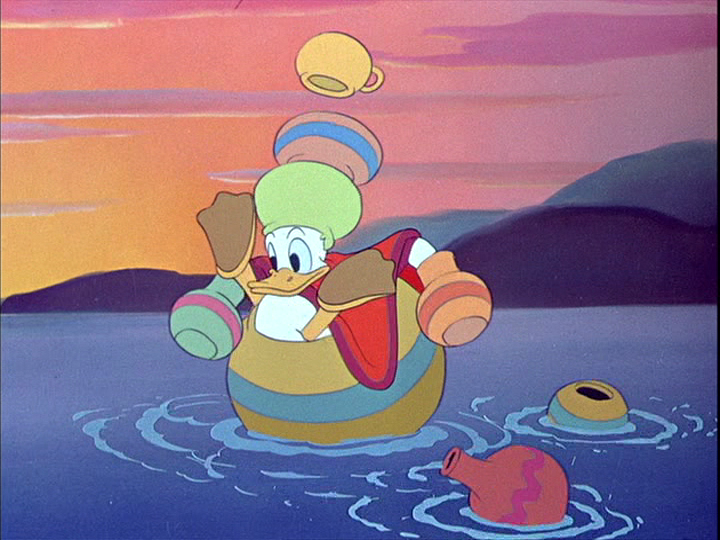

One of the most interesting things about SALUDOS AMIGOS (1947) is the various transitions between abstract and concrete approaches to the same subject. In live-action, we see Disney animators crossing sections of South America by plane, sketching different forms of local color while the narrator rattles off canned itineraries and cultural tidbits (“The music is strange and exotic,” etc.); eventually the sketches become cartoons. The cartoons, in turn, go from abstract to concrete and back again; each begins with a plane flying over not so much a country as a three-dimensional map, like the opening shot of Florida in DUMBO, with cities and countries indicated by printed names — a chip off of Uncle Walt’s globe, so to speak. This becomes a more concrete location as soon as the plane lands. And then the cartoon might turn relatively abstract again, as in the semi-drippy final sequence, “Watercolor of Brazil,” which culminates in arty silhouette effects after red drops of paint turn into storks, yellow drops into bananas, and then the bananas into crows. Or on a more subtle level, the visually prosaic antics of Donald Duck as a naive and affable American tourist suddenly becomes a kitsch extravaganza of pictorial and color values, as duck and assorted pottery go toppling down a mountain slope into the sea, while the bay is lit by a sunset that resembles a hemorrhage. Like some of the train shots in DUMBO, it is calendar art raised to a level of stupefied genius.

Even more than other Hollywood features, Disney’s are manifestly factory products in which in the personalities and effects of score of individuals are blended and absorbed, including influences from previous films: much as Howard Hawks borrows from CASABLANCA in TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT, the sequence about Pedro the Plane in SALUDOS AMIGOS seems to owe something to ONLY ANGELS HAVE WINGS. With so many identities at play in the features, it should come as no surprise that so many of them are uneven. The extraordinary thing is that such teamwork often worked as well as it did. In BAMBI, a lyrical grasp of the textures, colors, and shapes of plant life is juxtaposed with a vulgar anthropomorphism in the animals that implies an antithetical approach and attitude toward nature – analogous, perhaps, to the cosmetic “improvements” made on Hugh Hefner’s Playmates over the years, particularly when public hair was excluded.

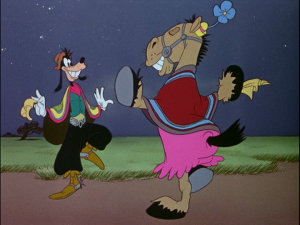

A parenthetical concern. I have a special fondness for a chummy Disney horse who appears in drag in both the Goofy-gaucho section of SALUDOS AMIGOS and the second half of ICHABOD AND MR. TOAD. (If it isn’t exactly the same character, they’re very close cousins.) Does my liking for that horse reflect a dislike or fear of real horses, or does it make me like real horses more? I suspect it somehow manages to do both.

I have no particular fondness for scorpions. But when I see the mating movements of a couple of them synchronized to square-dance music in one of the True-Life Adventures, I feel that a crime is being committed. Not so much a crime against scorpions — I imagine they couldn’t care less — as a crime against me and my relationship to scorpions.

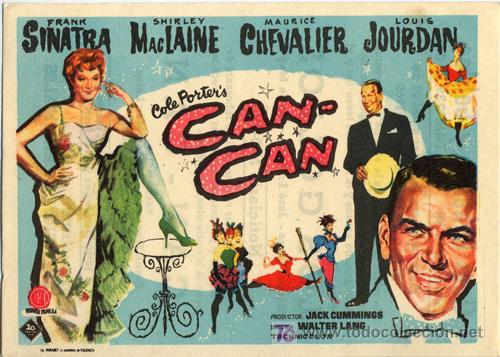

A day in Disneyland, August 1971. It looks even newer than it did in 1956, the first and only other time that I visited. Technologically, it was and is one of the most extraordinary things in America. Who could blame Krushchev for wanting to see it when he visited the U.S. in 1959? Everyone appeared to assume at the time that he must have been joking, but even cinematically, there’s much more of interest in Disneyland than one could have conceivably found on the set of CANCAN at the Fox Studios, which he was allowed to visit.

In the Haunted House here – one of the undisputed masterpieces of the park, and a relatively recent addition – the programmed effects are nearly all heightened developments of cinematic possibilities and principles. You step first into a circular low-ceiling waiting room decorated with family portraits; the doors close, the lights dim, the walls grow higher and higher and the family portraits stretch out accordingly, until eventually it’s like being at the bottom of a well. The doors open, and everyone gets into little cars – continues on a journey up and down hills in a nocturnal setting, through a graveyard; past a disembodied and speaking female head that’s clearly a projected (but three-dimensional) image; countless other delights. It is as “purely cinematographic” as the flight of Mephisto over western Europe in Murnau’s FAUST, just as the “trip sequence” in 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY is partially echoed in a Trip into the Cyclotron ride in Tomorrowland. On your way out of the Haunted Houseyour car passes a mirror which reveals that a grinning ghoul is sitting next to you.

Film is also centrally used in the Trip to the Moon, to depict simultaneously the receding Earth and the approaching satellite. Straight movie theaters and projections of various kinds are in evidence everywhere. And what is Main Street, U.S.A. , which stands at the entrance gate, but the set for a nostalgia film like STRAWBERRY BLONDE or MEET ME IN ST. LOUIS? Disney once gave an interesting account of the governing principle: “It’s not apparent at a casual glance that this street is only a scale model. We had every brick and shingle and gas lamp made five-eights true size. This costs more, but made the street a toy, and the imagination can play more freely with a toy. Besides, people like to think their world is somehow more grown up than Papa’s was.”

Midnight or so, passing back through the gates and into the cosmic reaches of the Disneyland parking lot, I look up at a dazzling skyful of stars, every constellation in its appointed place – stars poised and ready like raindrops about to fall. Are they Disney’s too?

***

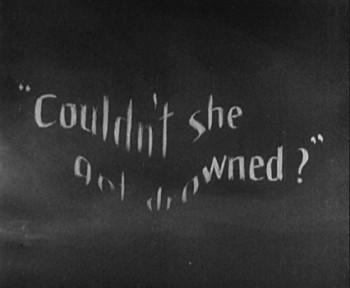

A troubled conclusion. Ultimately, the strengths and weaknesses of Disney’s art are both bound up in its well- preserved and self-sustaining innocence, its refusal or inability to move beyond a child’s perspective. Within these boundaries, its capacity to elicit certain emotions is uncanny: at least half of the people I know were scared out of their wits by the Wicked Witch in SNOW WHITE when they were children – as I recall, I was pretty jumpy myself – and to recognize Disney’s power and pre-eminence as the Supreme Heartcrusher today, all one has to do is witness the forcible separation of Dumbo from his mother at a kids’ matinee, where the scene will invariably

produce a disconsolate chorus of howls.

Apart from the terror, there is all the cute, cuddly humor, frequently built around a kitsch version of the Arcadia myth or the awkwardness or mere embarrassment of being a child in certain situations; cf., respectively, the nauseating centaurs moved around to Beethoven’s “Pastoral” in FANTASIA, the turtle painfully making its way

up a flight of stairs in SNOW WHITE.

The probable key to Disney’s success is that he has shown himself capable of understanding the way that children think and feel better than any other filmmaker of his time. The question that remains is how wisely and how well he put this special understanding to use. I don’t think it’s a question that children alone can answer and I don’t think it can be answered simply. I suspect that a lot of us are going to continue to be bothered by it, and bothered a lot, for a very long time.

End Notes:

1. At least three of its songs — “Someday My Prince Will Come,” “Heigh-Ho,” and “One Song” — have entered the jazz repertoire and served as graceful frameworks for improvisations by Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Dave Brubeck, and many others (a practice initiated by Brubeck, although Davis made it fashionable). Other “Disney” songs to have served this function include “When You Wish Upon a Star” and “Give a Little Whistle” from PINOCCHIO, “Alice in Wonderland,” and “Chim Chim Cheree” from MARY POPPINS, the latter performed by John Coltrane.

2. Poncet is probably the most exhaustive of the French Disney critics; see in particular her L’esthetique du dessin animé (A.G. Nizet, 1952).