From the Chicago Reader (January 18, 2002). — J.R.

**** (Masterpiece)

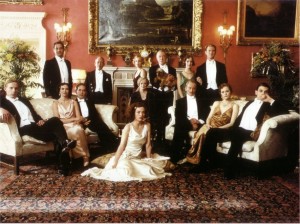

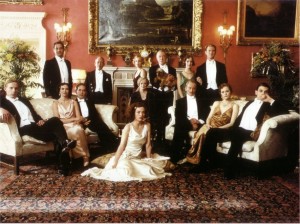

Directed by Robert Altman

Written by Julian Fellowes

With Eileen Atkins, Bob Balaban, Alan Bates, Charles Dance, Stephen Fry, Michael Gambon, Richard E. Grant, Derek Jacobi, Kelly Macdonald, Helen Mirren, Jeremy Northam, Clive Owen, Maggie Smith, Kristin Scott Thomas, and Emily Watson.

Critical consensus about any movie is impossible, but judging from end-of-the-year polls, Robert Altman’s Gosford Park is widely recognized as a masterpiece. Perhaps because the English period setting and the mainly English cast encouraged the septuagenarian Altman to curb many of his smart-alecky tendencies, he can finally be credited with something resembling a mature comedy-drama — that is to say, a measured and balanced one — for the first time since the 70s.

For all his many accomplishments, Altman sometimes doesn’t know when to stop underlining dramatic points, or exposing the silliness and vanity of his characters, or piling on miniplots. This makes it all the more impressive that he’s now given us a beautifully proportioned work in which 30 fairly well defined characters don’t seem excessive, most of the plot points aren’t hyped, and the director’s ridicule, while far from absent, isn’t allowed to dominate our own responses. Read more

From the March 31, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

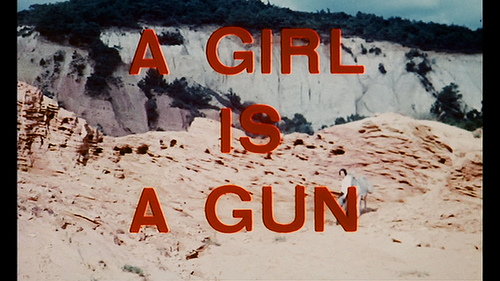

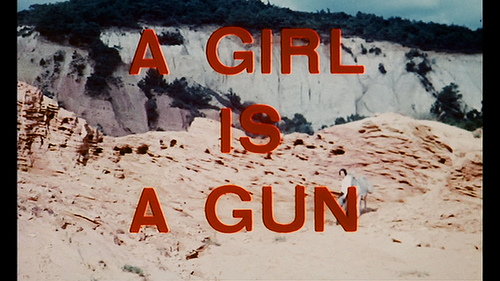

Luc Moullet: Agent Provocateur of the New Wave

Almost 30 years have passed since I wrote a heated article about French filmmaker Luc Moullet for Film Comment — the first extended defense of his movies and his film criticism in English. But the first American retrospective devoted to him is only now opening, at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Only 8 of his 32 films will be included, and some of my favorites are missing. Still, it’s been worth the wait.

Moullet, who grew up in the sticks, the son of a mail sorter and a typist, started writing for Cahiers du Cinéma in the 50s, when he was in his teens, and he’s still a critic today. Brigitte Bardot is seen reading Moullet’s book on Fritz Lang in Godard’s Contempt (1963), and his Politique des Acteurs came out in 1993. But only a fraction of his major writing has been collected. He was the first to write at length about Samuel Fuller and Edgar G. Ulmer and the first at Cahiers to champion Luis Buñuel. Neither a formalist nor an ideologue, he has a particular feeling for film style that in 1958 led him to compare the gratuitous camera movements in Douglas Sirk’s The Tarnished Angels to the run-on sentences in its source novel, William Faulkner’s Pylon. Read more

From The Guardian (August 31, 2002). Having more recently attended a 35-millimeter screening of Greed (not the longer version put together by Rick Schmidlin) at the St. Louis Humanities Festival, on April 6, 2013, I was delighted to see all 240 seats in the auditorium filled (another twenty were turned away); most of the audience remained and were clearly enrapt, and the majority stuck around for an hour-long discussion afterwards.

Thanks to the very generous help of a reader, Abe Slaney, in clearing up the format problems in this post, I’m reposting it. — J.R.

Legends about the ‘complete’ Greed have existed ever since Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer reduced Erich von Stroheim’s footage to ten reels and released the results in 1924. What they released, containing the only surviving footage, is scheduled to be shown twice in the National Film Theatre’s Stroheim retrospective.

Rick Schmidlin’s four-hour reconstruction on video of what the film might have been, also showing twice at the NFT, should be regarded as a study version. It suggests what some of the longer versions of Greed might have been like, though it isn’t in any way a replica of any of those versions. Schmidlin’s main sources, apart from the ten-reel version and a new score, are Stroheim’s ‘continuity screenplay,’ dated March 31, 1923, and hundreds of rephotographed stills of missing scenes — sometimes with added pans and zooms, sometimes cropped, often with opening and closing irises.

Read more