Written for Moving Image Source [movingimagesource.us], and posted there on October 9, 2008. — J.R.

“A writer’s reputation,” Lionel Trilling once wrote, “often reaches a point in its career where what he actually said is falsified even when he is correctly quoted. Such falsification — we might more charitably call it mythopoeia — is very likely the result of some single aspect of a man’s work serving as a convenient symbol of what other people want to think. Thus it is a commonplace of misconception that Rousseau wanted us to act like virtuous savages or that Milton held naive, retrograde views of human nature.”

Although Orson Welles is rightly regarded as someone whose creative work partially consisted of his own persona, he remains unusually susceptible to mythmaking of this sort. This is because he often figures as someone who both licenses and then becomes the scapegoat for vanity that isn’t entirely — or even necessarily — his own. Quite simply, many of those (especially males) who obsess on the “meaning” of “Orson” are actually looking for ways to negotiate their own narcissism and fantasies of omnipotence.

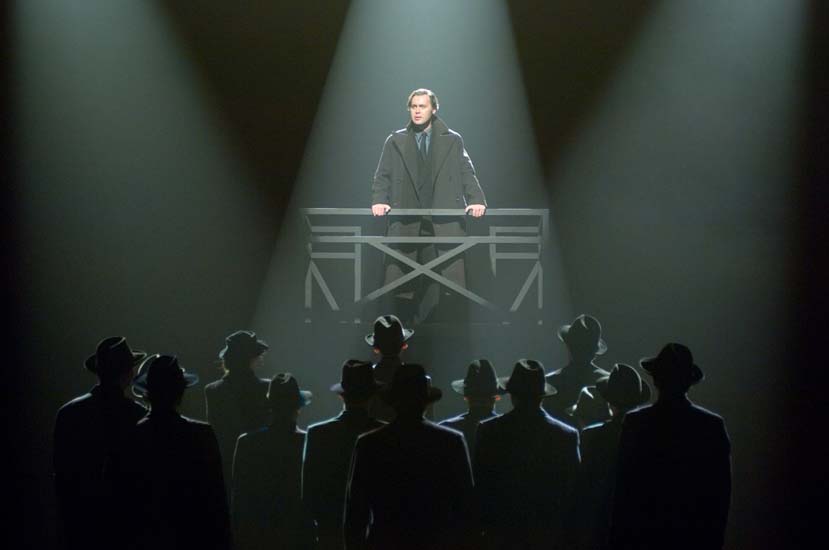

It’s part of the special insight of Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles, which premiered last month at the Toronto International Film Festival, to perceive and run with this aspect of the Welles myth, which is already implied in its title. This energetic and entertaining movie, which still lacks a U.S. distributor, was scripted by the couple Holly Gent Palmo and Vincent Palmo, closely adapting a 2003 novel by Robert Kaplow about a teenage boy in 1937 who joins Welles’s legendary Mercury Theatre stage production of Caesar in the minor part of Lucius. This was a modern-dress, bare-stage presentation celebrated for the conceit of making Shakespeare’s characters contemporary Italian fascists, and for employing “Nuremberg” lighting.

The film is greatly assisted by much research into the original stage production and a very adroit impersonation of the young Welles by English actor Christian McKay. And even though it is limited both as history and as Welles portraiture, it remains wholly on target in suggesting some of the motives for Welles mythopoeia. Thus one of the key scenes depicts the liberated vanity of the Mercury Theatre players that immediately follows the triumph of the opening night performance, as reflected in their idle chatter while they bask onstage in their victory. Indeed, the same euphoric self-regard can be found in virtually all of the film’s young characters, including a writer (Zoe Kazan) befriended by the hero who isn’t part of the Mercury troupe; in every case but hers, Welles is basically the magical force that unleashes and validates everyone’s egotism.

Despite the fact that the movie celebrates collective effort, and benefits a great deal from its own version of it, self-regard is the main dish on display, and Welles is credited as both the chef and the narcissistic role model. In fact, the “me” that appears first in Me and Orson Welles also appears last in the story, long after the Welles character has evaporated into legend.

Kaplow’s novel is also clearly attuned to this particular aspect of Welles-fixation; on the book’s second page, Richard Samuels, the teenage hero, is already gazing into a mirror and comparing himself to Gary Cooper, Cary Grant, and Fred Astaire (a conceit that the film’s casting of teenage heartthrob Zac Efron in the part makes halfway plausible). But Kaplow complicates and muddles matters somewhat with some of his ethnic details — most notably, by making his Richard Jewish and then having Welles improbably call his Jewish set designer Samuel Leve a “credit-stealing, son-of-a-bitch Jew” after the latter complains about not getting credit for his work in Caesar’s program, which leads Richard to leap to Leve’s defense.

The screenwriters, however, omit virtually all of the novel’s Jewish details (including even the character of Marc Blitzstein, who composed Caesar’s incidental music), and given the particular story Linklater has in mind, this simplification actually clarifies the proceedings. The credit dispute remains in the story, but without the intervention of either anti-Semitism or Richard — whose own battle with Welles crops up later.

Welles mythopoeia may help to explain why the least researched of all Welles biographies, David Thomson’s Rosebud — that is to say, the one most invented out of whole cloth — is commonly regarded by nonspecialists as the best, presumably meaning the most apt and insightful even while it imputes various failings to the man (including racism, classism, and declining productivity) that have no demonstrable basis in fact. Two characteristically unsupported sentences in Rosebud: “There is sometimes a perilous proximity of old-fashioned racial stereotype and yearning sympathy” (posited in Welles’s affection for some black people and black music) and “Welles…always liked his revolutionaries to be sophisticated and well-heeled” (an assertion refuted by the Brazilian fishermen and communists he insisted on hanging out with in 1942, to the consternation of some “well-heeled” government officials and studio spies).

But because Thomson is clever enough to know what some people want to believe about Welles as well as what they prefer to ignore, the falsity of his portrait “rings true” according to the myth, and for many people it continues to hold water. To some extent, Kaplow seems to be banking on a similar trait in his own readers.

By his own account, Kaplow’s hero, Richard Samuels, grew out of his efforts to imagine Arthur Anderson, the young lute player who appeared in a famous photograph of the Welles stage production, increasing his age by about three years so that his fictional counterpart could become Welles’s romantic rival. Correspondingly, Kaplow’s curiosity about what gave Welles’s fascist Caesar its political resonance and impact in 1937 is minimal, so that one may be left wondering, in spite of his and Linklater’s meticulous recreations, why the production proved to be such a smash success. (John Houseman’s memoir Run-through, clearly used as a major resource, conveys this period flavor much better.) And the film also sometimes reverts to standard -issue shorthand in establishing late-Depression atmosphere — such as employing a pastiche of Benny Goodman’s famous January 16, 1938, Carnegie Hall performance of “Sing, Sing, Sing,” perhaps the single most overused emblem of swing music employed in American movies. (The second most overused emblem, Duke Ellington’s “Solitude,” is also used.) More generally, it gives us the attributes of a young Welles that might inspire a teenager’s envy and imagination while omitting many of the other traits that would complicate this scenario.

There’s general agreement that Welles was self-absorbed. But one way of distinguishing mythopoeia from biography is whether or not his other distinguishing traits — such as his compulsive self-criticism (which could sometimes be even more severe than the charges of his detractors) and his desire to compensate for his self-absorption with certain forms of charm and generosity — are factored into the portrayal.

Me and Orson Welles (film and novel) is intermittently attentive to the latter but completely oblivious to the former, offering a Welles who insists on being called a genius and refuses any form of self-criticism. It also depicts him as a man who could nurse serious grudges over minor challenges to his authority — something my own research has failed to turn up. But insofar as Welles continues to be a shining beacon for the self-regard of others, the portrait hits a mythological bull’s-eye.