Four years ago, I requested and received authorization from Pere Portabella to publish in English translation two lengthy texts of his — a lecture that he gave in 2009 when he was awarded an honorary doctoral degree by the Universidad Autónoma of Barcelona and the even lengthier (over twice as long) “Prologue” he wrote and published for Mutaciones del Cine Contemporáneo (2010), the Spanish translation of Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003), which I coedited with Adrian Martin. The first of these was an unsigned English translation that Nicole Brenez sent to me; the second was a makeshift translation hastily but generously done by two of Rob Tregenza’s students at Virginia Commonwealth University, Daniel Schofield and Caleb Plutzer.

The original plan was for both of these pieces to appear in the online journal Lola, but for a variety of reasons, this didn’t pan out, and both these texts were recently returned to me. For now, I am opting to reproduce the translation of the speech in three consecutive installments. — J.R.

II

In the early eighties, a significant about-face took place, especially in the European Union and the United States. All of the avant-garde movements’ residual ideas, or those protected under that name, were driven out, as the need for a unique form of politically correct, artistically appropriate thought was ushered in, and anything that smacked of “deconstruction” was swept away. Read more

Four years ago, I requested and received authorization from Pere Portabella to publish in English translation two lengthy texts of his — a lecture that he gave in 2009 when he was awarded an honorary doctoral degree by the Universidad Autónoma of Barcelona and the even lengthier (over twice as long) “Prologue” he wrote and published for Mutaciones del Cine Contemporáneo (2010), the Spanish translation of Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003), which I coedited with Adrian Martin. The first of these was an unsigned English translation that Nicole Brenez sent to me; the second was a makeshift translation hastily but generously done by two of Rob Tregenza’s students at Virginia Commonwealth University, Daniel Schofield and Caleb Plutzer. The original plan was for both of these pieces to appear in the online journal Lola, but for a variety of reasons, this didn’t pan out, and both these texts were recently returned to me. For now, I am opting to reproduce the translation of the speech in three consecutive installments. — J.R.

Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, the fiction and essay writer, defines “lyrical poetry as that which does not strictly have any ‘recipients’, because it does not communicate any semantic content at all; instead it has just ‘users’, and their ‘use’ consists precisely of taking the place of the ‘id’ in the poem. Read more

Four years ago, I requested and received authorization from Pere Portabella to publish in English translation two lengthy texts of his — a lecture that he gave in 2009 when he was awarded an honorary doctoral degree by the Universidad Autónoma of Barcelona and the even lengthier (over twice as long) “Prologue” he wrote and published for Mutaciones del Cine Contemporáneo (2010), the Spanish translation of Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (2003), which I coedited with Adrian Martin. The first of these was an unsigned English translation that Nicole Brenez sent to me; the second was a makeshift translation hastily but generously done by two of Rob Tregenza’s students at Virginia Commonwealth University, Daniel Schofield and Caleb Plutzer.

The original plan was for both of these pieces to appear in the online journal Lola, but for a variety of reasons, this didn’t pan out, and both of these texts were recently returned to me. For now, I am opting to reproduce the translation I have of the speech, in three consecutive installments. — J.R.

Speech by Pere Portabella for the event at which he is awarded an Honorary Doctoral Degree by the Universidad Autónoma of Barcelona

I

In order to conceive a film, I must always place a blank sheet of paper in front of me. Read more

Written for Filmkrant‘s “Slow Criticism”, February 2010 (no. 318). — J.R.

There’s a personal reason why Ne Change Rien comes together for me in a way that few music documentaries do. Eight years ago, I was approached by Rick Schmidlin, the producer of the 1998 re-edit of Touch of Evil (on which I’d served as consultant), about writing or directing — in any case, helping to conceptualize — a documentary about jazz pianist McCoy Tyner. This led to a lengthy conversation with Tyner in Chicago and then a three-page treatment that I prepared with cinematographer John Bailey via phone and email, which concluded, “Any film that’s about listening, as this one will be, will also be about looking — predicated on the philosophy that the way one looks at musicians already helps to determine the way one listens to them.”

For me one of the ruling ideas was that few jazz films, apart from a handful of the very best, focused enough on the spectacle of jazz musicians listening to one another. And I saw (and heard) the whole thing as a two-way process — the way one listens should dictate the way one looks, as well as vice versa. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 13, 1993). — J.R.

RISING SUN

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Kaufman, Michael Crichton, and Michael Backes

With Sean Connery, Wesley Snipes, Harvey Keitel, Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa, Kevin Anderson, Mako, Ray Wise, Stan Egi, Stan Shaw, and Tia Carrere.

Before seeing Rising Sun and then reading the Michael Crichton thriller it’s based on, I happened to read four negative reviews of the movie, and was more than a little taken aback by them. Here are samples of what I found:

“Following the cut-and-dried police procedural structure of the book, cowriter and director Philip Kaufman has soft-pedaled the critique of Japanese behavior stateside, which may reduce justification for protests against the film, but also removes much of the material’s bite.” (Todd McCarthy, Variety)

“Trying to transcend the material, the director loses the novelist’s crude but compelling urgency.” (David Ansen, Newsweek)

“Crichton’s novel was largely powered by his animus against the Japanese business culture, and perversely, you miss his outrage.” (Richard Schickel, Time)

“Crichton, in his novel, was accused (with some justification) of Japan-bashing, but if his vision of Japanese executives as omnipotent control freaks had a racist tinge, it was also sinister fun. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (October 26, 1990). — J.R.

HENRY & JUNE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Philip Kaufman

Written by Philip and Rose Kaufman

With Fred Ward, Uma Thurman, Maria de Medeiros, Richard E. Grant, Kevin Spacey, and Jean-Philippe Ecoffey.

“There are larval thoughts not yet divorced from their dream content, thoughts which seem to slowly crystallize before your eyes, always precise but never tangible, never once arrested so as to be grasped by the mind. It is the opium world of woman’s physiological being, sort of a show put on inside the genito-urinary tract. There is not an ounce of man-made culture in it; everything related to the head is cut off. Time passes, but it is not clock time; nor is it poetic time such as men create in their passion. It is more like that aeonic time required for the creation of gems and precious metals; an embowelled sidereal time in which the female knows that she is superior to the male and will eventually swallow him up again. The effect is that of starlight carried over into day-time.”

This elegant huffing and puffing belongs to Henry Miller, writing about the journals of Anais Nin in a 1939 essay called “Un Etre Etoilique” (A Starlike Being), collected in The Cosmological Eye. Read more

In memory and appreciation of Sidney Lumet (1924-2011). This appeared in the March 17, 2006 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

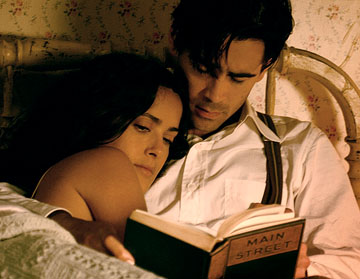

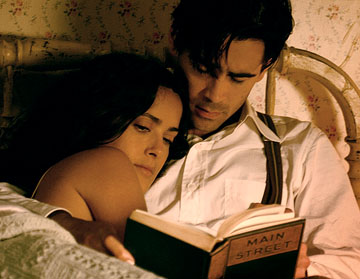

Ask the Dust *** (A must see)

Directed and written by Robert Towne

With Colin Farrell, Salma Hayek, Idina Menzel, Donald Sutherland, Eileen Atkins, and William Mapother

Find Me Guilty *** (A must see)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Lumet, T.J. Mancini, and Robert J. McCrea

With Vin Diesel, Ron Silver, Peter Dinklage, Linus Roache, Tim Cinnante, Annabella Sciorra, Raul Esparza, and Alex Rocco

John Fante’s slim 1939 novel Ask the Dust, one of four autobiographical novels about his surrogate, Arturo Bandini, has a childlike lyricism that recalls William Saroyan and Jack Kerouac. “I climbed out the window and scaled the incline to the top of Bunker Hill. A night for my nose, a feast for my nose, smelling the stars, smelling the flowers, smelling the desert, and the dust asleep, across the top of Bunker Hill. The city spread out like a Christmas tree, red and green and blue. Hello, old houses, beautiful hamburgers singing in cheap cafes, Bing Crosby singing too.” In this novel Fante celebrates his 20-year-old self from a vantage point of almost a decade later, but unlike Saroyan and Kerouac, he also criticizes that earlier self. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Spring 1989). The on-screen breakdown of Jean-Pierre Léaud in Out 1, alluded to below, was lamentably removed by Rivette shortly after its Rotterdam screening — attended, if memory serves, by no more than five or six people. — J.R.

When he died last July, Hubert Bals had already selected twenty films for his eighteenth Rotterdam Festival, and embarked on retrospectives devoted to John Cassavetes and Jacques Rivette. Rather than try to second-guess his preferences for the rest of the programme, interim director Ann Head and her able staff invited several filmmakers associated with Bals to complete the selection with neglected titles of their own or other choices. This quick galvanizing of energies resulted in the best of the six consecutive Rotterdam festivals I’ve attended. The event was haunted by recent losses – Cassavetes and Jacques Ledoux, as well as Bals – but the legacies they left behind were vibrantly present on the screen.

Raul Ruiz brought two engaging new featurettes, Tous les nuages sont des horloges ( a free adaptation of a Japanese mystery coscripted by his students) and L’Autel de l’amitié (a series of Diderotesque dialogues about the French Revolution), both bristling with visual invention. Read more

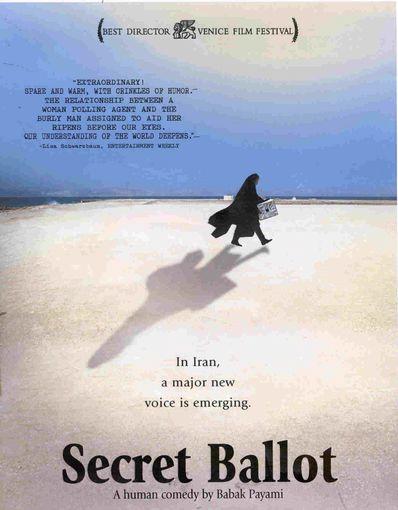

From the Chicago Reader (August 30, 2002). — J.R.

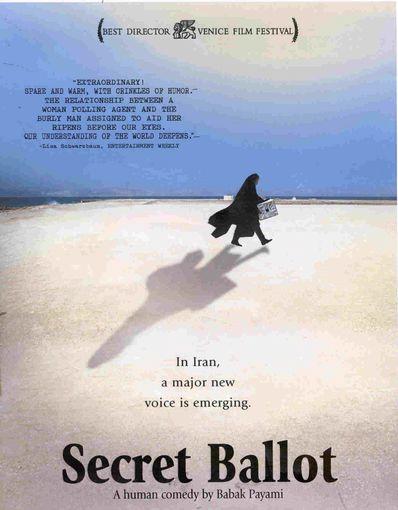

Secret Ballot

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Babak Payami

With Nassim Abdi, Cyrus Ab, Youssef Habashi, Farrokh Shojaii, and Gholbahar Janghali.

Secret Ballot is…a demonstration of the fact that society at large has much more integrity than the forces that govern it. This is as true in Iran as it is in the United States. — Babak Payami

I’m embarrassed to admit that I was one of the people who fell for the story that circulated not long after the invasion of Afghanistan that George W. Bush had asked to see a subtitled print of Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar. It was sheer wishful thinking, the result of a hope that sympathy for the innocent Afghan victims of the American assault would somehow prevail over all the confusion and self-righteousness.

The sources of the rumor soon went silent, but it had already circled the globe. I searched the Internet and turned up allusions to it in France’s L’Humanité, Britain’s Guardian and Observer, and Australia’s The Age, as well as in Brazilian and Dutch papers. Read more

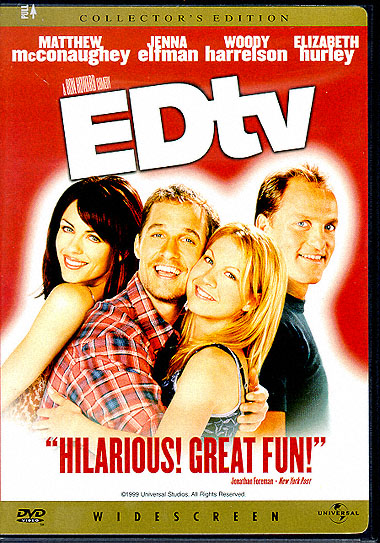

From the Chicago Reader (March 26, 1999). — J.R.

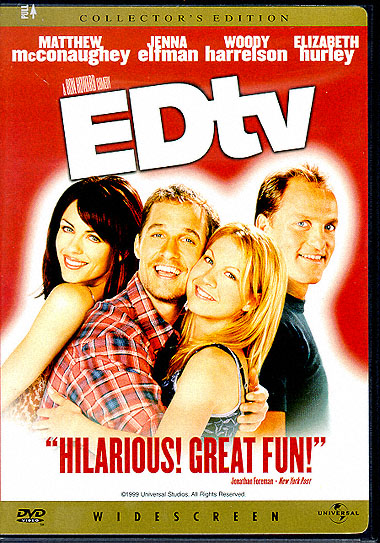

EDtv

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Ron Howard

Written by Lowell Ganz and Babaloo Mandel

With Matthew McConaughey, Jenna Elfman, Woody Harrelson, Sally Kirkland, Martin Landau, Ellen DeGeneres, Rob Reiner, Dennis Hopper, and Elizabeth Hurley.

I tend to like Ron Howard movies. They’re usually energetic, Capra-like popular entertainments that respect the audience — not a common virtue these days. Howard is one of the few remaining filmmakers from the Hollywood studio tradition who can be counted on to offer honest diversion without making any undue claims for what he’s doing — and I include everything from Grand Theft Auto and Night Shift to Splash and Cocoon, from Gung Ho and Parenthood to the underrated Far and Away, Backdraft, and The Paper, and even dubious efforts such as Willow and Apollo 13. Even when his films are satirical, as Gung Ho is, they don’t offer their commentaries from the top of soap boxes, and their messages are sweet tempered rather than caustic.

EDtv conforms to this pattern, though it runs up against a current conundrum — how can one criticize the excesses of the contemporary media without blaming the audience? Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 2002). It was great to see this amazing, radical masterpiece on TCM, even if Ben Mankiewicz consistently mispronounced the director’s name and gave almost completely erroneous information about it. — J.R.

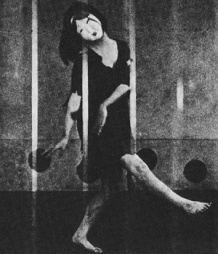

Teinosuke Kinugasa’s mind-boggling silent masterpiece of 1926 was thought to have been lost for 40 years until the director discovered a print in his garden shed. A seaman hires on as a janitor at an insane asylum to free his wife, who’s become an inmate after attempting to kill herself and her baby. The film’s expressionist style is all the more surprising because Japan had no such tradition to speak of; Kinugasa hadn’t even seen The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari when he made this. Yet the rhythmic pulsation of graphic, semiabstract depictions of madness makes the film both startling and mesmerizing. I can’t vouch for the live musical accompaniment by Pillow, an unorthodox quartet that’s reportedly quite percussive, but its instrumentation — clarinet, dry ice, tubes, electric guitar, accordion, contrabass, cello — sounds appropriate. 75 min. Presented by Columbia College and Chicago Filmmakers. Columbia College Ferguson Theater, 600 S. Michigan, Friday, February 1, 8:00, 773-293-1447.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 3, 1998). — J.R.

Out of Sight

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Steven Soderbergh

Written by Scott Frank

With George Clooney, Jennifer Lopez, Ving Rhames, Don Cheadle, Dennis Farina, Albert Brooks, Steve Zahn, and Catherine Keener.

The Brigands: Chapter VII

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Otar Iosseliani

With Amiran Amiranachvili, Alexi Djakeli, Dato Gogibedachvili, Guio Tzintsadze, Nino Ordjonikidze, Keti Kapanadze, and Nino Kartsivadze.

Which would you rather see? A Hollywood thriller with hot stars whose director is so alienated from his material that he’s reduced to a kind of ingenious doodling while his characters disintegrate? Or a witty, despairing French-Russian-Italian-Swiss art movie set in 16th-century Georgia, Stalinist Georgia, contemporary Georgia, and contemporary Paris, whose writer-director is so much in command of his materials that he can plant the same actors in all four settings yet provide a seamless continuity?

My question is mainly rhetorical because it’s already been decided for most people reading this. Out of Sight, a major Universal release written by Scott Frank and directed by Steven Soderbergh, is playing all over town and will be around for weeks; The Brigands: Chapter VII, written and directed by Otar Iosseliani, doesn’t even have a U.S.

Read more

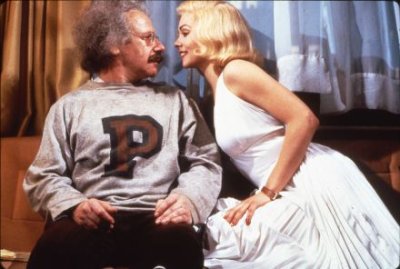

Otto Preminger took LSD before making this demented, vulgar 1968 screwball musical about hippies taking over the world, in which his own trip is re-created as Jackie Gleason’s. This isn’t exactly funny, and it’s the last Preminger film one would pick to convince a skeptic of his talent, but it’s fascinating throughout. The satirical plot pits hippies against corporate gangsters lorded over by someone named God (Groucho Marx in his last film performance), whom Gleason used to work for. The cast mainly consists of aging TV stars (Gleason, Marx, Carol Channing, Frankie Avalon, Arnold Stang) and Hollywood has-beens (Peter Lawford, Burgess Meredith, George Raft, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Fred Clark). Preminger’s celebration of the counterculture may be peculiar (Channing serves as the major go-between and, oddly enough, the sanest character), but it’s certainly sincere. Don’t miss the hallucinatory Garbage Can Ballet — the apotheosis of this cheerful garbage can of a movie — and the sung credits at the end. 98 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the August 14, 1997 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

COLD HEAVEN

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Nicolas Roeg

Written by Allan Scott

With Theresa Russell, Mark Harmon, James Russo, Talia Shire, Will Patton, Richard Bradford, and Julie Carmen.

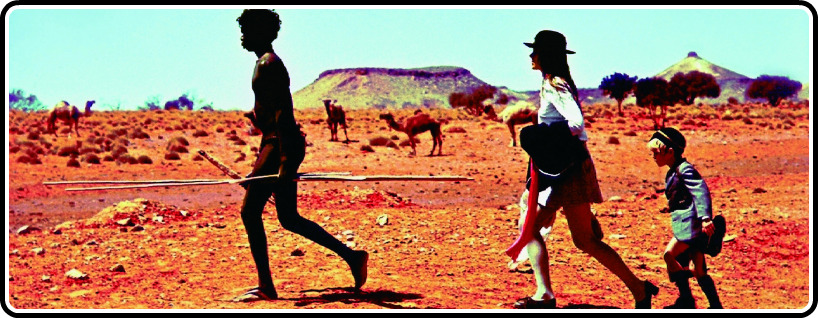

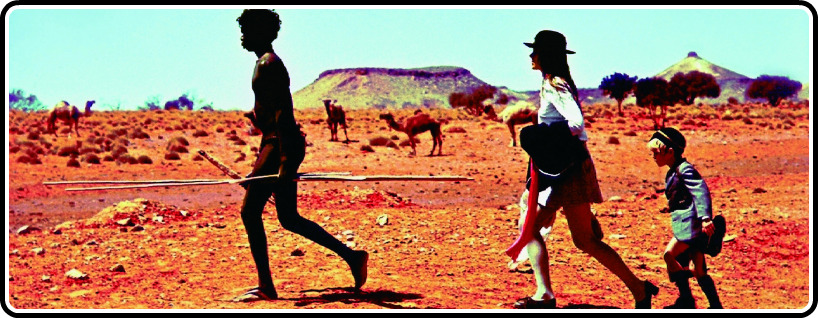

The sexy, volatile cinema of Nicolas Roeg might be said to operate under a kind of curse. Born in London in 1928, Roeg entered movies as a clapper boy at the age of 22 but didn’t become a cinematographer until his early 30s. After shooting such interesting films in the 60s as The Masque of the Red Death, Fahrenheit 451, and Petulia, he directed his powerful and still-dangerous Performance (in collaboration with Donald Cammell) in 1968, but then had to wait two years for Warner Brothers to release it.

After Roeg’s first solo directorial effort (Walkabout, 1971) came his first and only commercial hit (Don’t Look Now, 1973). He followed that up with two controversial cult items (The Man Who Fell to Earth, 1976, and Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession, 1979). In 1982 he made a feature (Eureka) that had a very limited release. Next in line was Insignificance (1985), then another feature with virtually no theatrical life in the United States (Castaway, 1986), then a third limited release (Track 29, 1988). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 2, 1997). — J.R.

Films by Rainer Werner Fassbinder

I’m still trying to figure out what I think of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945-1982), the German whiz kid who’s the focus of a nearly complete retrospective showing at the Film Center, Facets Multimedia Center, and the Fine Arts over the next couple of months. An awesomely prolific filmmaker (he turned out seven features in 1970 alone), Fassbinder became the height of Euro-American fashion during the mid-70s, then went into nearly total eclipse after his death from a drug overdose — reminding us that the fate of a fashionable filmmaker is often to be discarded (as, more recently, have been David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino).

As skeptical as I often was in the 70s about Fassbinder as a role model, I’ve been more than a little disconcerted by the speed with which he’s vanished from mainstream consciousness. Having now seen two dozen of his 37 features, one of his four short films, and one of his four TV series — though I haven’t seen many of them since they came out — I find much of his work, for all its deliberate topicality, as fresh now as when it first appeared. Read more